Wilfred Owen: Echoes from the Trenches

"My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity."

Hello, dear history buffs!

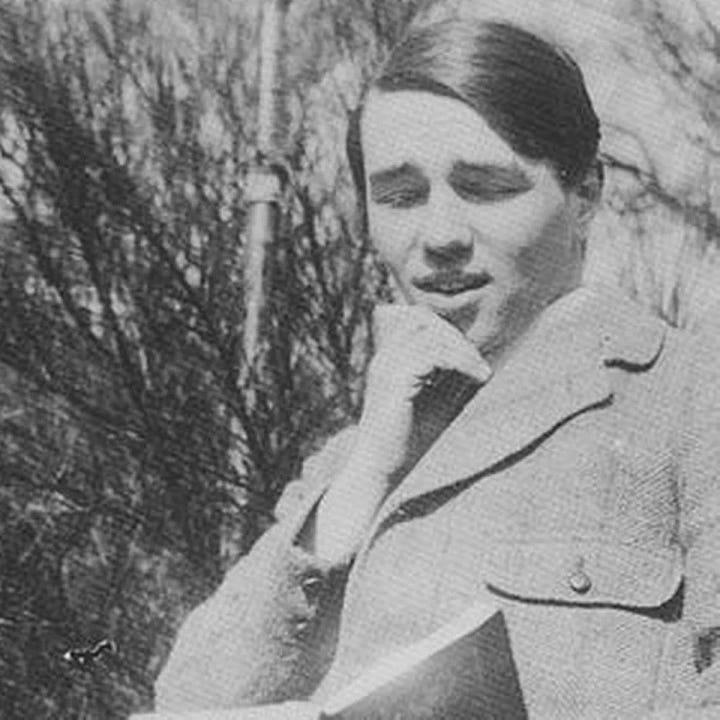

In our previous post, we discussed the story of Siegfried Sassoon as the first part of our series exploring the lives of three WW1 poets. Today, we shift our attention to another one of these, who also happens to be my personal favorite: Wilfred Owen.

This series is building up to my upcoming adventure with Leger Holidays (stay tuned for more details at the end!)

Early Life

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen was born in the town of Oswestry, Shropshire, on 18 March 1893. As the firstborn of Thomas and Susan Owen, he was soon joined by siblings Mary Millard, Harold, and Colin Shaw Owen. The early years of young Wilfred's life were spent in the comfort of a house owned by his grandfather, Edward Shaw, whose passing in 1897 and the subsequent sale of the house led the family to pack their bags and move to Birkenhead. It was here that Owen's academic journey began, first at the Birkenhead Institute and later at Shrewsbury Technical School.

Years later, by then a young man, Owen moved to Bordeaux, France, where he immersed himself in privately teaching English and French at the Berlitz School of Languages.

World War I, however, was ready to change the course of everyone's lives. While many heeded the call to arms immediately, Owen initially hesitated. In October 1915, he enlisted with the Artists Rifles, marking the beginning of a journey that would profoundly influence his legacy.

“What passing-bells for these who die as cattle? — Only the monstrous anger of the guns."

On 4 June, Owen was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Manchester Regiment. In a letter to his mother (one among several others that he would write), he painted a vivid picture of his early days in the regiment and the stark contrast between the luxuries of England and the grim realities of war:

"My own dear Mother,

I have joined the Regiment, who are just at the end of six weeks' rest. The journey here was filled with 'awful vicissitudes.' I recall the luxury of Folkestone, with its deep carpets — a stark contrast to the mud here — and the impeccably dressed staff. But since setting foot on Calais quays, dryness has been a luxury. The persistent dampness has even invaded my sleeping bag and pyjamas. My current abode? A stone floor, sharing space with two other officers. The rest of the house is a cacophony of servants and the band, arguably the roughest bunch I've ever encountered. Their coarse language is a constant, almost like a background score to our lives here.

The faces of fellow officers wear a look of strain, something I've never seen before and hope never to see again outside of prisons. As for the men, they're just as Bairnsfather depicted — devoid of expression, almost numb."

Owen's remarks provide a window into the difficulties he faced. The trenches, often just deep ditches dug into the ground, became the soldiers’ makeshift homes and fortresses against the enemy. The presence of mud was a constant companion, clinging to boots and uniforms and making even the simplest movements a laborious task. The smell was overwhelming, a mix of wet earth, rotting sandbags, and the unfortunate reality of human waste and decay. Rats thrived in these conditions, growing bold enough to nibble on sleeping soldiers. The ever-present threat of enemy fire, gas attacks and the eerie sounds of exploding shells made sleep a rare luxury.

As 1916 drew to a close, Owen found himself on the move again. On December 29th, he left for France, this time with the Lancashire Fusiliers. Within a week of his arrival, he found himself transported to the Front crammed into a cattle wagon. The sounds of war were immediate and inescapable. The front lines were no longer abstract concepts; they were now a lived reality.

Owen described a particularly frightening incident in a letter dated January 16, 1917: "In the Platoon on my left, the sentries over the dug-out were obliterated. One of these lads was my first servant, whom I had chosen not to retain. Had I kept him by my side, he might still be alive, for servants aren't tasked with sentry duty. During the most intense bombardments, I positioned my own sentries halfway down the stairs for some semblance of protection. Despite these precautions, one young man was blown down, and I fear he's been blinded. He was the only one in my charge to be harmed that day. The officer leading the adjacent platoon was so deeply affected by the ordeal that he's now hospitalized. As for me, I'm holding on, as well as one can in such circumstances.”

This episode found its way into the verses of one of his most famous and powerful poems, The Sentry:

"He's lost his sight, and sobs aloud,

‘O sir, my eyes – I'm blind – I'm blind, I'm blind!'

Coaxing, I held a flame against his lids

And said if he could see the least blurred light

He was not blind; in time the world would mend."

That January was transformative. Owen had been exposed to and gone through the worst that war has to offer. He soon realized that in that context and environment, the line between living and dying was incredibly thin and fragile. Traumatic events were not rare occurrences but an everyday part of the soldiers’ lives. The exhaustion and the presence of death gradually destroyed even the strongest wills.

Not only did the war claim lives, but it also destroyed minds. And Owen himself wasn't immune to these horrors. In April 1917, he was launched into the air by a trench mortar explosion, leaving him lying unconscious for several days on an embankment surrounded by the gruesome remains of a fellow soldier.

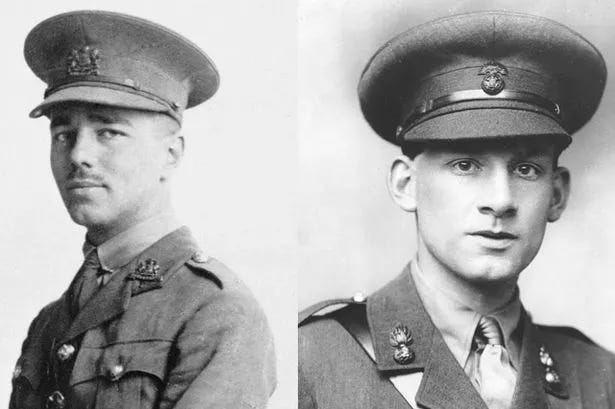

As expected, the experience took its toll. Owen was evacuated back to Britain, a victim of what was then called "shell-shock.” This condition, now recognized as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), became a silent epidemic among soldiers. Institutions like Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh were established in response to this growing crisis, aiming to treat the shattered minds returning from the front lines. It was there that Owen's path would cross with another significant figure of the war poetry movement, Siegfried Sassoon.

Poets in Arms

Their initial meeting was an unassuming one. Owen, a great admirer of Siegfried's writings, stepped into the bedroom and discovered the man meticulously polishing his golf clubs while dressed in a stylish purple suit. Later, on recalling that first encounter, Sassoon remarked on Owen's "charming honest smile" and the respect with which he approached, almost as if consulting a superior officer. He also confessed an "instinctive liking" for the younger poet.

Owen described the moment in a letter dated 22 August 1917: “(…) I have beknown myself to Siegfried Sassoon. Went to him last night (my second call). The first visit was one morning last week. The sun blazed into his room making his purple dressing suit of a brilliance — almost matching my sonnet! He is very tall and stately, with a fine firm chisel'd (how's that?) head, ordinary short brown hair. The general expression of his face is one of boredom.”

That day, Owen didn't express his desire to write poetry until he was about to leave the bedroom. Siegfried gave him a straightforward instruction: "Sweat your guts out writing poetry."

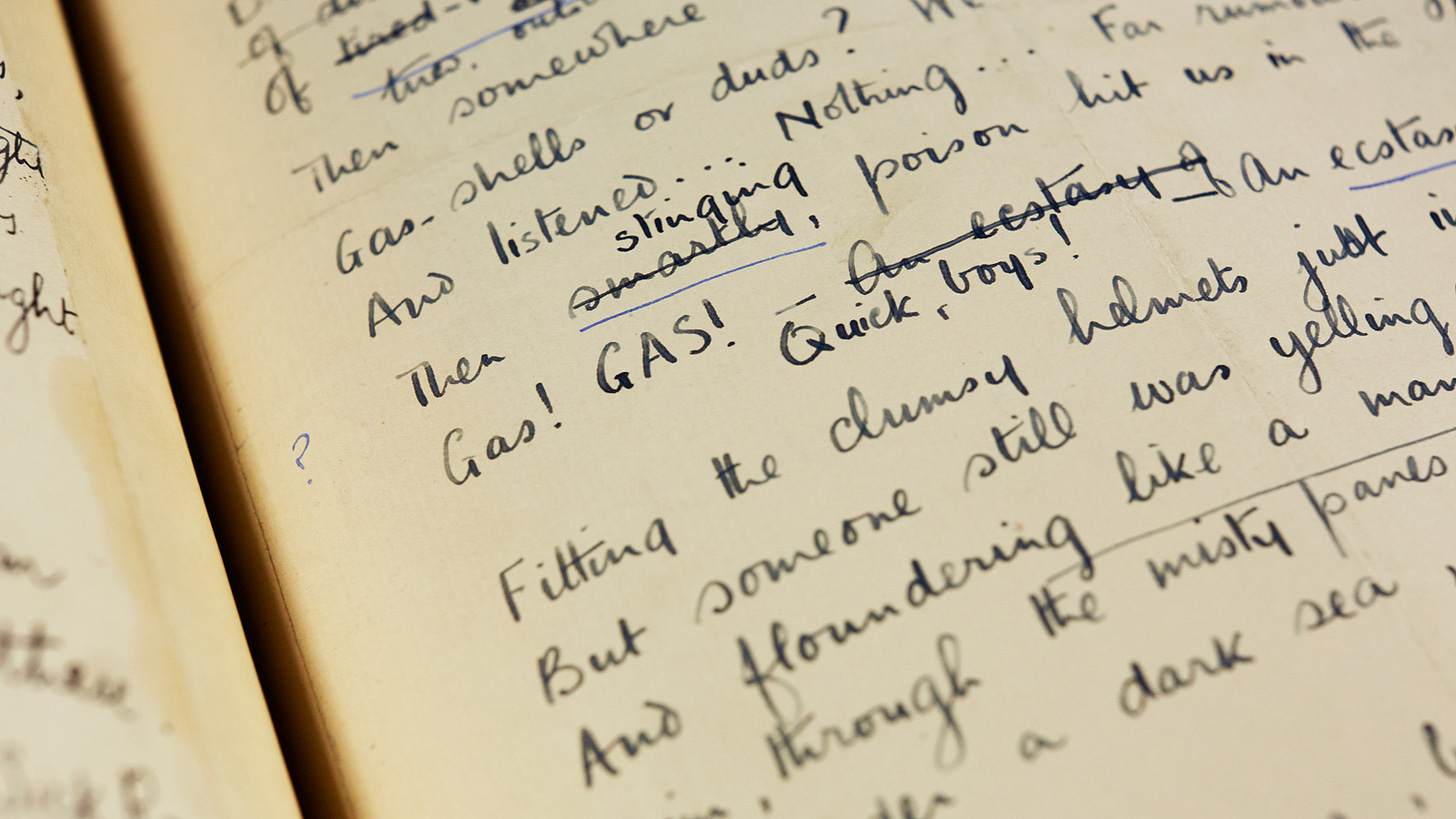

Encouraged by his doctor, writing had become a therapeutic outlet for Owen. He became the editor of Hydra, the hospital magazine, and penned some of his most iconic poems during this period, including "Anthem for Doomed Youth" and "Dulce et Decorum Est."

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor of girls' brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.— Anthem for Doomed Youth

Over time, the dynamic between Owen and Siegfried evolved into that of a pupil and mentor, and their bond intensified. The aspiring poet often turned to Sassoon for guidance, even having his mother send his manuscripts from home for Sassoon's review, whose initial impressions of Owen's work were far from flattering. Sassoon seemed somewhat skeptical of Owen's poetic prowess. This sentiment was evident when he scribbled a note on a copy of Hydra he was sending to a friend, remarking, "The man who wrote this brings me quantities and I have to say kind things. He will improve, I think!"

His prediction came true, and his perception changed dramatically as Owen's craft matured. The turning point came with Anthem for Doomed Youth. Upon reading it, the older poet was struck by its brilliance, later reflecting that it was at that moment that he truly recognized the "masterly quality" of Owen's verse: “There was enough in it to indicate the power and originality of what he afterwards produced, and I rejoiced in my discovery of an authentic poet.”

Interestingly, despite Siegfried's evident influence on Owen's work, shaping and refining his voice, he later downplayed his role. Yet, the historical record tells a different story. The original manuscript of "Dulce et Decorum Est", for example, bears the marks of Sassoon's suggestions and revisions.

"His imagination worked on a larger scale than mine. My trench-sketches were like rockets, illuminating the darkness. They were pioneering in their own right. But it was Owen who demonstrated how poetry could be crafted from the raw horrors and disdain of war. His devoted discipleship towards me perhaps influenced my judgment. He often told me I was the one man he had yearned to meet. I consider it a significant achievement to have been able to nurture his genius." Sassoon also remarked: "We could not align with the older generation's belief that it was sweet and fitting to die for one's country. Such a death was inevitable, perhaps, but hardly enlightening. Owen's poems, in particular, were crafted to jolt people out of their complacency."

Soldiers like Owen and Sassoon, having witnessed the war's horrors firsthand, turned to poetry to process and communicate their experiences. Both poets were critical of the fervent pro-war propaganda that had engulfed England in the lead-up to the war. The shared ideals drew them even closer as time went on, and they sought solace in each other's company. "There was much comfort in his companionship... His hero being in sore need, he could bring him gentle and intuitive support", Sassoon wrote.

The depth of this relationship has been the subject of much speculation. While there's no concrete evidence to confirm a romantic involvement between the two, their correspondence, filled with warmth, admiration, and affection, suggests an emotional intimacy that maybe went beyond mere friendship. It's important to notice that this was a time when homosexuality was not only a societal taboo but was also criminalized in the UK. The infamous trial of Oscar Wilde in 1895, where he was convicted for "gross indecency" and sentenced to two years of hard labor, was still fresh in public memory. Such convictions were not just legal judgments but carried with them a heavy societal stigma, leading many to suppress or hide their true feelings and identities. The societal constraints of their time meant that even if there were deeper feelings between Owen and Sassoon, they would likely have been kept hidden, expressed only in private moments and coded language.

Owen's sexuality became a source of debate and, at times, deliberate erasure after his death. His brother Harold went to great lengths to curate and ‘sanitize’ his legacy, not only by selectively editing Owen's letters but also by destroying his only diary, perhaps in an attempt to shield his brother from a society that might not have been ready to accept the complexities of human relationships. Harold defended these actions by suggesting that those who inferred a ‘homosexual inclination’ in Owen were misinterpreting his "emotional tendency to hero-worship." Sassoon, for his part, admittedly had relationships with men throughout his life, including with Ivor Novello and Prince Philipp of Hesse.

The Final Salute

Owen's departure from Craiglockhart in November 1917 marked the end of an intense and transformative chapter in his life. As he prepared to leave, Sassoon handed him a sealed envelope. Inside was £10, equivalent to £887.58 in today's currency.

In a letter, Owen playfully chided Sassoon for the gift, "Smile the penny! This Fact has not intensified my feelings for you by the least – the least frame."

But what followed was a raw and candid outpouring of emotion. Owen likened Sassoon to a pantheon of figures, both historical and personal, writing, "Know that since mid-September, when you still regarded me as a tiresome little knocker on your door, I held you as Keats + Christ + Elijah + my Colonel + my father-confessor + Amenophis IV in profile. The mathematical sum of these comparisons? A simple and profound declaration: I love you, dispassionately, so much, so very much, dear Fellow."

He acknowledged the profound impact the poet had on his life, stating, "If you consider what the above Names have severally done for me, you will know what you are doing. And you have fixed my Life – however short. You did not light me: I was always a mad comet; but you have fixed me."

After that, Owen and Sassoon had the opportunity to see each other one last time. They enjoyed a meal at the Reform Club and later spent some time at a friend's house. As the evening progressed, Owen accompanied Sassoon back to the hospital in Lancaster Gate, where he was recovering from a head injury. It was during this time that Owen revealed his intention of returning to the front lines. Sassoon strongly opposed this idea and even went as far as threatening to stab Owen in the leg to prevent him from going back.

In one of his last letters to Sassoon, Owen says: "I have been incoherent ever since I tried to say goodbye on the steps of Lancaster Gate. But everything is clear now: & I’m in hasty retreat to the Front . . . What more is there to say that you will not better understand unsaid. Your W.E.O."

Little did they know that fate had decided they would never share another moment.

The Last Verse

Owen went back to the Front at the end of August 1918. On 1 October, he showcased his leadership and bravery as he led units in a daring assault on enemy strong points near the village of Joncourt. His acts did not go unnoticed, and he was recommended for the Military Cross, as described in a heartfelt letter to his mother, penned between the 4th and 5th of October 1918:

"I have been recommended for the Military Cross; and have recommended every single N.C.O. who was with me! My nerves are in perfect order. I came out in order to help these boys – directly by leading them as well as an officer can; indirectly by watching their sufferings that I may speak of them as well as a pleader can. I have done the first. Of whose blood lies yet crimson on my shoulder where his head was – and where so lately yours was – I must not now write. It is all over for a long time. We are marching steadily back.

Moreover, the war is nearing an end."

Tragically, just a month after writing this letter, on 4 November, Owen met his untimely end during the crossing of the Sambre–Oise Canal.

As the world celebrated the end of the Great War on Armistice Day, the bells of Shrewsbury rang out in jubilation. But for one mother, those same bells tolled in mourning, as she received the heart-wrenching telegram informing her of her son's death.

Exciting News!

Invited by my good friend Paul Reed, I'm about to embark, in the first week of September, on a unique journey that I'm thrilled to share with you all: the War Poets Tour, promoted by Leger Holidays! This awesome adventure, of which I'm very grateful to be a part, will allow me to dive even deeper into the stories of Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen and many other soldiers who used the power of poetry to capture the war experience.

I'm very excited and eagerly anticipate sharing every moment of the tour with you. It's going to be amazing. So subscribe, and stay tuned!

To learn more about the War Poets Tour and many others, visit the website of Leger Holidays.

Thank you! I admire both poets but didn’t know much of their backstories.

Amazing history. I've always been deeply touched by war poetry, ww1 in particular. As a matter of fact, purchased a small pocket book with ww1 poems just today, would not surprise me if Owen's work is among the poems. Was considering sharing some of them on Substack if they resonate witth me, I feel like they have so much powerful messages to convey.