Unwrapping mummies at parties and grinding them into paint

the Victorians never missed a chance to be bizarre

takes a deep breath

So, I was scrolling through Instagram the other day, minding my own business, when I came across this crazy video. It’s got these two climate activists, gotta be in their 80s, whacking away with a hammer and chisel at the glass case protecting the Magna Carta. You know, that ancient document from 800 years ago that laid the foundation for modern democracy? Yeah, that one. These activists claimed they were doing it to highlight the disastrous effects of climate change, arguing that “there will be no freedom, no lawfulness, no rights if we let climate breakdown turn into the catastrophe that’s being predicted.”

I really dig fighting climate change, but attacking historical artifacts is just dumb, in my humble opinion.

But while I was watching this, it really hit me just how fragile these old documents and historical artifacts are. We just assume they’ll be around forever, but really, it wouldn’t take much for them to vanish. We have countless examples to mention: the legendary Library of Alexandria, anyone? Or more recently, the National Museum in Rio, which housed over 20 million artifacts before it went up in smoke in 2018, thanks to a delightful combo of insufficient funding, nonexistent preventative measures, and good old-fashioned corruption?

However, despite these constant reminders of how terrible we are at basic preservation, it seems we still can’t resist messing with what little remains.

Just look at the Titanic. On the 100th anniversary of the disaster, a New York auction house put up for sale a shocking $185 million worth of items salvaged from the wreck. We're talking eyeglasses, antique currency, jewelry, clothing, and even a massive 17-tonne chunk of the hull, ripped clean off in the ship's final, violent moments. Ever since people found the wreck back in 1985, there have been multiple trips to the debris field, with over 5,500 artifacts being taken from the site.

This obsession and desire to grab pieces of the past seems to have taken different forms over time and depending on the culture, but I feel that in the 19th century, things got especially out of control. I mean, we're talking about a time when people were absolutely insane and were trying to do all sorts of crazy stuff, like using giant mirrors to send messages to aliens. And in a world where even seemingly unreasonable ideas could quickly be taken to wild extremes, it's no surprise that Egyptomania (an obsession with ancient Egypt) was able to grip people in Europe and America and spread like crazy.

"People of Egypt: You will be told by our enemies, that I am come to destroy your religion. Believe them not.” - Napoleon Bonaparte

It all started in 1798 with a military expedition led by a guy named Napoleon Bonaparte. At the time, France was at war with Britain, and Napoleon, who was already making a name for himself as a brilliant military strategist, saw an opportunity to strike a blow against the British by invading Egypt. The country was nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, but it was also a key link in the trade routes between Europe and India, which meant that controlling it could give France a major advantage.

In July of that year, the young French general set sail from France with a fleet of over 300 ships and an army of around 40,000 men, including a group of 167 specialists in various fields such as mathematics, engineering, art, and science, known as the “savants.” This might initially sound a little random, but it was actually a really smart move. Napoleon knew that to really conquer Egypt he needed more than just brute force: he also needed to understand the land, the people, and the culture.

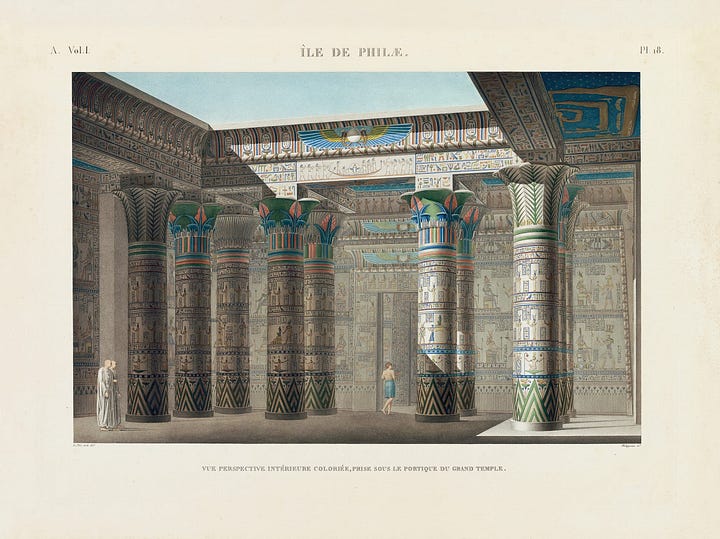

The savants followed the French army around, documenting everything they saw. They sketched pyramids, measured temples, collected plants, animals, and minerals, created detailed maps (including the first comprehensive map of the Nile Valley), studied local farming techniques and religious practices, and even did a bit of grave-robbing (for science!).

The most groundbreaking discovery of this whole adventure, however, came purely by chance in 1799, when French soldiers were digging near the town of Rashid to build a fort and found a big stone slab that we now call the Rosetta Stone. This stone was actually part of a bigger monument that was built in a temple a long time ago, and it had a message carved into it ordered by King Ptolemy V. When the temple was closed around 392 AD, probably because a Roman emperor named Theodosius I wanted to shut down temples that weren’t Christian, the big monument was broken and moved to Rosetta. There, it was used to help build a fort called Fort Julien, which is where the French soldiers found it.

The cool thing about the Rosetta Stone, and the reason why we still talk about it to this day, is that it had the same message written in three different ways: in Greek, Demotic (a simplified form of ancient Egyptian writing), and hieroglyphs. While people could read Greek and Demotic, nobody could figure out what the hieroglyphs meant - until 1822. That's when a really smart French linguist called Jean-François Champollion used his knowledge of Coptic (a language that evolved from ancient Egyptian) and compared the inscriptions, finally deciphering them. This was a huge deal because it meant that people could finally read all the writing on ancient Egyptian temples, tombs, and scrolls, and learn all about Egypt’s history, religion, and how people lived back then.

Napoleon's military campaign was, let's say, a monumental failure, but his decision to bring the savants along was a stroke of genius. From their efforts came this amazing multi-volume book called the Description de l’Égypte - a super detailed record of everything they saw and learned, filled with beautiful illustrations and engravings, which brought Egypt closer than ever to people back home.

So, inspired by the stories of Napoleon's adventures, rich individuals started going to Egypt to see it all for themselves. Because of this, there was a big increase in travel literature during this time, as these adventurers documented and shared their own experiences in diaries, letters, and books. One such traveler was Amelia Edwards, a British novelist and journalist who visited in 1873-1874. In her bestselling "A Thousand Miles Up the Nile," published in 1877, she vividly described the overwhelming experience of seeing the pyramids up close:

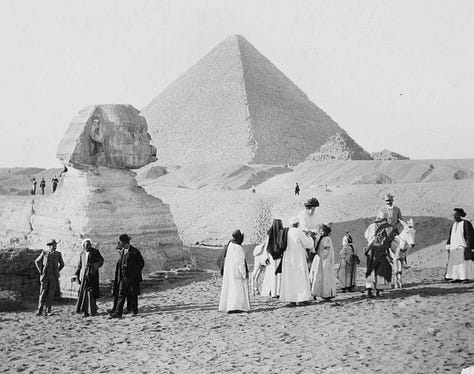

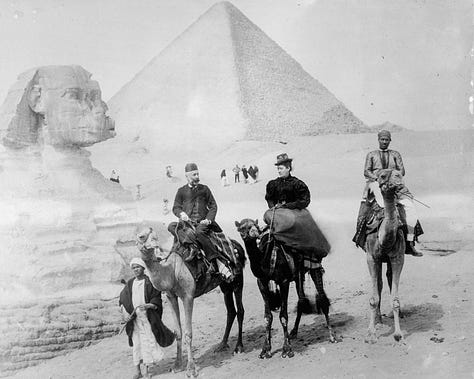

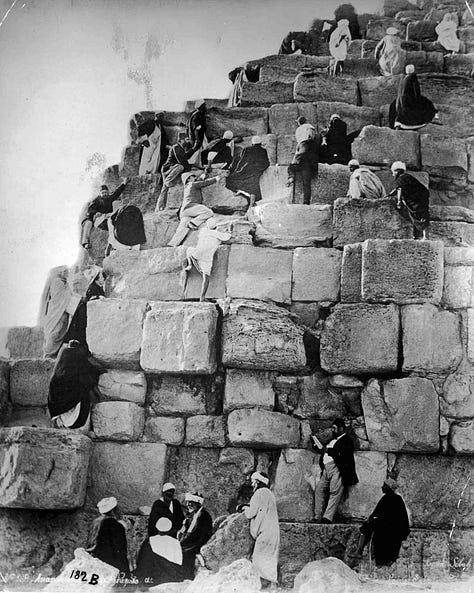

"The first glimpse that most travellers now get of the Pyramids is from the window of the railway carriage as they come from Alexandria; and it is not impressive. It does not take one's breath away, for instance, like a first sight of the Alps from the high level of the Neufchâtel line, or the outline of the Acropolis at Athens, as one first recognises it from the sea. The well-known triangular forms look small and shadowy, and are too familiar to be in any way startling. And the same, I think, is true of every distant view of them — that is, of every view which is too distant to afford the means of scaling them against other objects. It is only in approaching them, and observing how they grow with every foot of the road, that one begins to feel they are not so familiar after all. But when at last the edge of the desert is reached, and the long sand-slope climbed, and the rocky platform gained, and the Great Pyramid in all its unexpected bulk and majesty towers close above one's head, the effect is as sudden as it is overwhelming. It shuts out the sky and the horizon. It shuts out all the other Pyramids. It shuts out everything but the sense of awe and wonder."

The influence of these eyewitness stories eventually started to really catch on across Europe, and Egyptian symbols and patterns started popping up in the most unexpected places. You could see them on mass-produced consumer goods, like those fancy tea sets your grandma loves so much, all the way to the latest fashion trends and home decor. Need a new dress? Let’s add some Egyptian motifs. Redecorating the living room? How about some hieroglyphics on the wallpaper?

But if there was one place where Egyptomania reached truly epic and insane proportions, it was undoubtedly England. After all, we're talking about the Victorians! I have a bit of a soft spot for them, honestly, because they remind me of that eccentric aunt or uncle who always shows up at family gatherings with some wild new hobby or a crazy outfit - and I’m all for it.

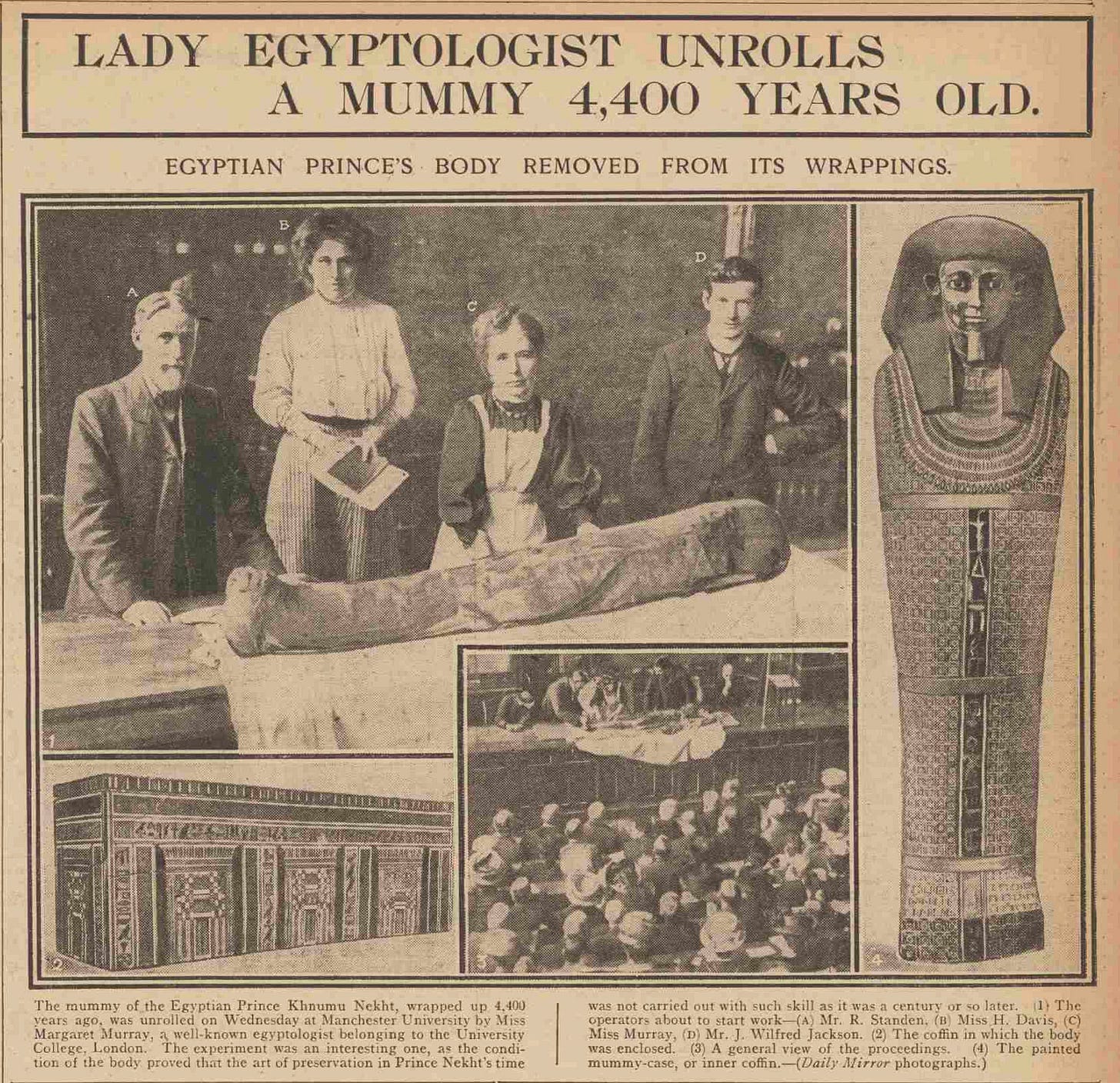

These people, it seems, never did anything halfway. When they fell in love with something, they went all in. The problem is that they often took their passions to the extreme, sometimes to the point where it became a bit dangerous or problematic. And when it came to Egypt, well, they were no exception. Because, you know, they were the Victorians. So, one day, they looked around and thought: “What could be more exciting than unwrapping a real, ancient mummy in front of all our guests?”

This brilliant idea led to one of the strangest and most unsettling trends of the time.

The Mummy Unwrapping Parties

Yes, read this heading twice.

I think it's pretty self-explanatory, but these… events? basically consisted of a bunch of rich individuals (it's always them) getting together to unwrap the preserved remains of an actual Egyptian mummy. I'm not kidding.

One of the most prominent figures in this peculiar form of entertainment was Thomas Pettigrew, a renowned surgeon and antiquarian. Pettigrew's first public mummy unwrapping took place in 1834 at the Royal College of Surgeons in London, but he went on to perform more than a dozen such events over the course of his career, often in lecture halls or private homes (presumably while Lord Fancypants could be heard complaining about the dreadful London weather, Lady Gertrude remarked on the wonderful quality of the tea being served, and everyone seemed to casually ignore the fact that an actual human being was being desecrated right in front of their eyes).

But where does one even find a mummy in the first place? It’s not like you could just pop down to the local corner store and pick one up, along with your favorite cheese and your favorite wine. The only way to do that was through the profitable underworld of antiquities smuggling.

This surge in interest naturally created a golden opportunity for dodgy dealers and tomb raiders, who, pretty soon, started looting gravesites left and right, trying their best to keep up with the demand for more mummies to destroy.

“It may be said of some very old places, as of some very old books, that they are destined to be forever new. The nearer we approach them, the more remote they seem: the more we study them, the more we have yet to learn. (…) This is true of many ancient lands, but of no place is it so true as of Egypt.” - Amelia Blanford Edwards

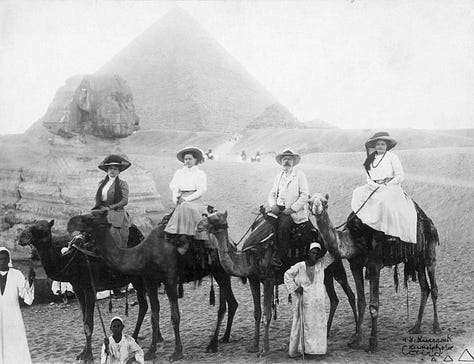

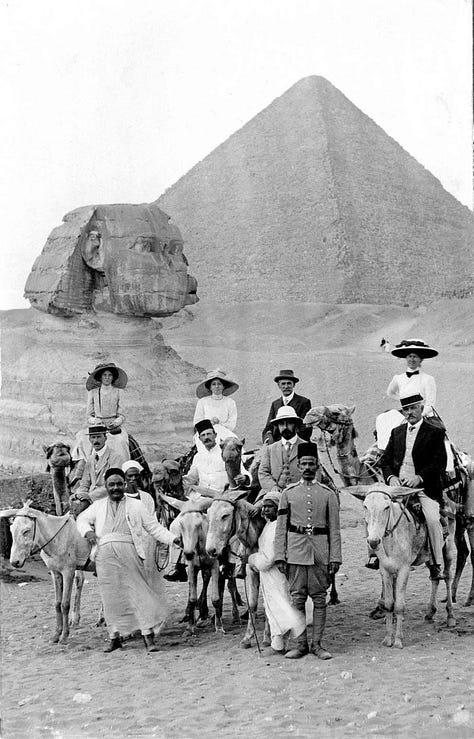

The second half of the 19th century also witnessed an Egyptian tourism boom, thanks largely to the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal, which made the journey from Europe considerably faster and cheaper.

Thomas Cook & Son, a pioneering British travel company established by Thomas Cook in 1841, quickly recognized the potential of this new market and began offering all-inclusive package tours that covered everything for a reasonable price (at least if you were upper class) — transportation, places to stay, and guided tours of the country’s top spots. The main attraction was perhaps a Nile River cruise where guests would hop on fancy riverboats and sail upstream to Luxor, making stops along the way at ancient temples, tombs, and monuments. It was definitely a genius business move that others soon copied with similar packages and itineraries, but Thomas Cook & Son stayed ahead of the game for quite some time.

Unfortunately, as expected, many Western tourists arrived with a superiority complex, disregarding local customs and norms, chipping off bits of monuments to take home as souvenirs, and even carving their initials into temple walls. Sure, most people were genuinely curious and respectful. But the overall dynamic was often one of unequal power and privilege.

“It would be hardly respectable, on one’s return from Egypt, to present oneself without a mummy in one hand and a crocodile in the other.” - Ferdinand de Géramb

The unrestrained looting escalated with this fresh wave of visitors to such atrocious levels that the streets of Cairo themselves became a gross spectacle. According to firsthand accounts, vendors openly sold mummified human body parts and completely desiccated corpses alongside everyday items like fruits and vegetables, and tourists from around the world queued up to purchase these gruesomely dehumanized remains.

Not everyone was thrilled about this, and some found the whole scene appalling. In 1894, American traveler Catharine Janeway vented her disgust, writing “I was much annoyed by an Arab, who had the hand of a mummy for sale; he followed me about, and kept thrusting this horrid object close to my face, telling that I should have it cheap.” For others, possessing looted Egyptian antiquities was a mark of status. And the more bizarrely obtained, the better.

For the most insane relic hunters, the ultimate prize was accessing the vast mummy pits scattered throughout the region, where mummies were excavated and sold directly on-site. A 1907 report in the Daily News from Perth, Australia, reported that a high-quality “pharaoh” could be bought for £200. A military commander or a “prince” (whatever that means) could be yours for the low, low price of £30. And if you really wanted to save your money, you could always go for a priest mummy at £12 to £15, or even a common pleb for just £1 10s. If you were lucky enough, you could even walk out with a complimentary set of amulets and scarabs.

The cultural and religious significance these artifacts held for the Egyptian people didn’t matter. All that mattered was the thrill of owning something rare, and the bragging rights that came with it.

In recent years, there have been increasing calls for museums and institutions to confront how they’ve benefited from exploiting other cultures’ artifacts and heritage, but meaningful repatriation efforts have been painfully slow, with only pitiful quantities returned after years of legal battles and foot-dragging.

Now, I’m gonna be honest. As someone obsessed with museums, this whole issue leaves me feeling conflicted about where I stand. I have spent countless hours walking through exhibits and collections, completely fascinated by all that history and stuff in front of me. But then I start thinking about how many of those items ended up there, and things get a whole lot more complicated.

There’s no magic answer here. It must be incredibly frustrating and challenging for museums to find a way to deal with this legacy of colonial theft (something that definitely needs to be done), while also struggling with existential and practical threats like keeping the lights on. Finding a middle ground is tricky, and what that middle ground even looks like is a whole other conversation we need to have. But as difficult as this situation might be, we can’t just sit back and do nothing.

On top of the repatriation of specific items, maybe a first step could be museums being more transparent about the origins of their collections and acknowledging the problematic histories behind many of these artifacts. They should actively seek out partnerships with the communities and countries from which these objects were taken, working together to find solutions that prioritize respectful sharing and cultural exchange over one-sided ownership. Let the people these artifacts came from have a voice in how they’re displayed, interpreted and shared.

Every journey starts with small actions, and the alternative - continuing to ignore or downplay these issues - is simply not an option anymore.

Ground Mummies Make Good Paint

Let me tell you one last terrifying thing that, as an artist, I just had to bring up before I end this.

Though various odd and unsettling stories exist in the world of art history, few compare to the dreadful story of Mummy Brown. This is not some historical color inspired by the beautiful hues of some sarcophagi or whatever. Mummy Brown was, quite literally, a paint made by grinding up ACTUAL MUMMIFIED HUMAN REMAINS into powder.

While we don't know exactly when it started, the earliest known record of its use dates back to the early 18th century, when, according to Philip McCouat, an art supply store in Paris called "À la momie" was selling paints, varnishes, and powdered mummies. The pigment supposedly offered a deep and rich hue that was different from anything else available at the time. And unsurprisingly, because that’s how we are, the art world went wild for it.

European painters could find the paint in well-stocked art supply shops, either as a loose powder to be mixed by hand or as pre-made paint tubes ready for use. It was an expensive pigment compared to other common colors of the time, but many artists considered the price worthwhile, as a single tube could last for months or even years.

It’s honestly quite terrifying how naturalized this became. So much so that in 1904, manufacturers like O’Hara and Hoar were openly placing ads in newspapers seeking ‘a 2,000-year-old mummy’ for paint production.

Perhaps most shocking is that until very recently people were still happily squeezing paint out of tubes filled with ground-up human remains like it was no big deal. In fact, the respected British color company Roberson & Co. continued selling “Mummy Brown” to artists through their catalog until 1933!

“From the heights of these pyramids, forty centuries look down on us.” - Napoleon Bonaparte

I’ve been obsessed with ancient Egypt since I was a kid, and I blame my mom, who has a history degree, entirely. Our house was always filled with books about pyramids and pharaohs that I just couldn’t get enough of. (By the way, one day I brought my favorite one to school to show my history teacher, thinking he’d be just as excited to see it as I was. Biggest mistake ever, because he, maybe more excited than I thought he would be, borrowed it and never gave it back. I’m still pissed about it to this day, and I really hope he stubs his toe every morning for the rest of his life.)

I get where the fascination comes from. Ancient Egypt is awesome. But as much as we love something, we can’t just grab pieces of it and treat them however we want.

I swear, it's not hard. Sometimes, all you have to do is pause and consider how you would feel if, say, some idiot came along and began digging up your grandmother’s grave in search of some shiny jewelry to sell on eBay. You’d be pissed, right? Of course, you would. Because that’s not some random object – it’s your memories and family’s history, too.

People 3,000 years from now will inevitably dig up all the stuff that our society was obsessed with. I’m sure they will probably find piles of unopened Funko Pops and will scratch their heads trying to come up with some deep, profound theories about their sacred or spiritual meaning, when, in reality, it was just a bunch of grown-ass adults obsessively hoarding plastic figures of their favorite TV characters (no judgment here, the tab next to where I’m writing this is literally the Lego website). But hey, future viewers reading this post - while you’re busy trying to make sense of our crazy world, please don’t pull the same grave-robbing crap we did to ancient civilizations, okay? We messed up on that front and we’re not proud of it. Yeah, I know, we may not deserve this much consideration given our awful track record. But Grandpa Bob and Aunt Karen would really rather not have their ashes sprinkled in some hipster’s latte. Some of us are really trying to do better here, and we’ve already got enough to answer for.

So, if you could just let us rest in peace when we’re gone, that’d be great.

I know it’s a lot to ask, but it would be appreciated.

Sounds good? Thanks!

Quite a few more blemishes on our history. Let us not forget that the face (particularly the nose) of the Sphinx was broken, perhaps deliberately. At one time, the vandalism was attributed to Napoleon's soldiers, but this claim has been refuted. [The nose was missing long before the French arrival, probably as early as the 15th century or perhaps even the 10th, and erosion has also taken its toll.] Thanks for sharing this, and I'll make it a point to boycott any parties at which mummies are unwrapped!

WOW please keep on and don’t prevent us from your great articles.