The students guillotined for speaking out against Nazi genocidal policies

On this day in 1943, the final act of resistance of the White Rose took place

On a chilly morning in February, the atmosphere inside the atrium of the University of Munich was tense and quiet. Hans Scholl, a 24-year-old medical student, and his 21-year-old sister Sophie arrived, carrying a suitcase not filled with books, but with bravery in the form of 1,700 anti-Nazi leaflets. It was February 18, 1943. Hans and Sophie didn't know yet, but they were about to step into history.

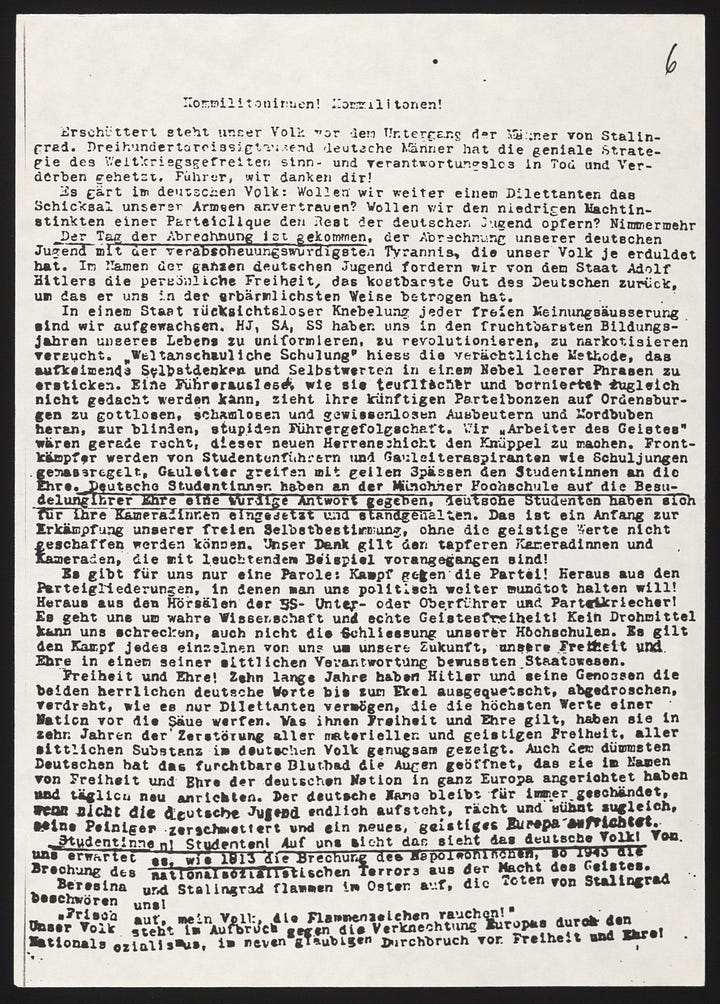

The Scholls, like they had done plenty of times before, started spreading their pamphlets around, dropping them off right outside classroom doors. These were part of a peaceful resistance movement led by The White Rose, a group made of a network of friends and intellectuals, which included Hans and Sophie, whose mission was to oppose Adolf Hitler's oppressive government and inspire Germans to resist.

That morning, after they were done distributing what was the White Rose sixth manifesto, the young siblings made their way to leave the building. But then, they realized that they still had around 100 leaflets left. They couldn't risk wasting such precious material, of course. To them, the leftover flyers were as precious as gold; although, in reality, they held a value far beyond any precious metal. In those pages resided the power of words and ideas. So, in a moment of impulsive courage or perhaps a calculated move, the Scholls (some accounts say just Sophie) turned back, ascended the atrium's grand staircase, and, as hoards of students started pouring out of their classrooms, tossed the remaining papers over the railing. The flyers soared through the air and landed in the hall below.

Jakob Schmid, a janitor working at the university, witnessed this quiet rebellion. The decision he made next changed lives forever, leading Hans, Sophie, and their brave friends towards an ending that was nothing short of tragic and heartbreaking.

“And thou shalt act as if

On thee and on thy deed

Depended the fate of all Germany,

And thou alone must answer for it.”

This may not be breaking news, but I can't tell you the story of the White Rose without mentioning that the socio-political climate in Nazi Germany during the period when the group started its activities was marked by an oppressive totalitarian regime where political opposition was met with severe punishment or death. And, by the way, the term 'political opposition' could refer to practically anyone – from an outspoken university student to that neighbor who seemed suspiciously unenthusiastic about the latest broadcast of a Hitler speech. The state-controlled propaganda machine operated by Joseph Goebbels worked tirelessly to maintain a narrative that glorified war and demonized the supposed enemies of the Reich. Within this context, most of the public conformed either out of loyalty or survival instinct, suppressing any discordant views.

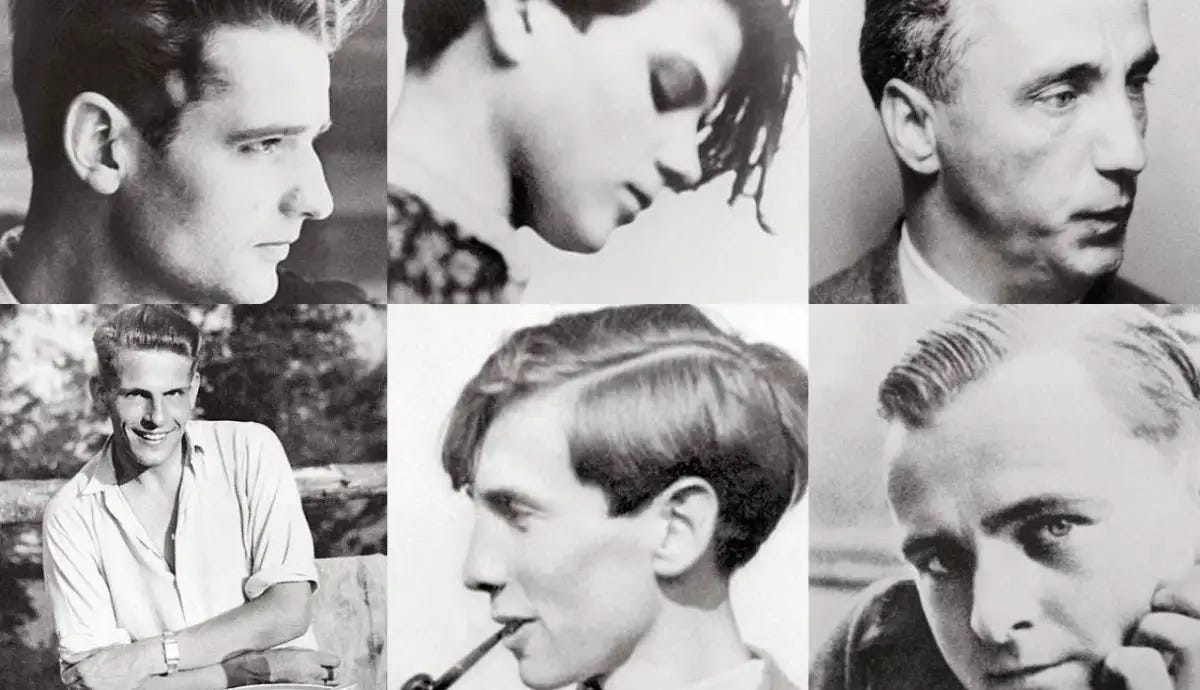

In 1942, when speaking out could mean your last breath, the White Rose bloomed. It started with a conversation among students gathering in secret to discuss their shared outrage at the injustices unfolding around them and a deep-seated horror at the atrocities committed in the name of their country. At the group's core were Hans and Sophie Scholl, alongside their colleagues (most of whom were medical students) Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, Christoph Probst, Traute Lafrenz, and a professor of philosophy, Kurt Huber.

Hans Scholl, Sophie Scholl, and Alexander Schmorell weren't always fierce enemies of the regime. Surprisingly, in their younger days, they got involved in different Nazi youth groups, caught up like many others in the patriotic fervor and nationalistic idealism encouraged within these organizations. The Scholls, as well as Schmorell, were in the Hitler Youth. Christoph Probst was associated with the German Youth Movement. Back then, it wasn’t really a choice to join these organizations - it's just what you did if you were young in Germany. These clubs operated under the guise of community and camaraderie, but their underlying objective was to indoctrinate the youth, from a very tender age, with anti-Semitic and militaristic dogmas, perpetuating a culture of blind allegiance to the Führer. This brainwashing built up die-hard supporters for Hitler’s vision - the one where he imagined his Third Reich would last a thousand years. So while Hans, Sophie, and Alex started out wearing those uniforms quite enthusiastically, you better believe they didn't stay that way once they saw through it all.

In 1936, the Nazi regime enforced a law that ordered the dissolution and official ban of all youth groups which were not under their direct control, restricting any kind of expression or association that didn't align with the party's beliefs. However, before this decision, Hans Scholl had already joined the Deutsche Jungenschaft 1.11, a group that promoted intellectual freedom and self-expression.

The grave repercussions of affiliating with the d.j.1.11 were realized on December 13, 1937, when Hans, then 19 years old, was arrested by the Gestapo alongside twenty other teenagers from Ulm. They faced severe charges including allegations of homosexual activities - another target for eradication under the Nazi regime's ruthless policies. Needless to say, being arrested on charges related to homosexuality during that period meant facing social exclusion, imprisonment, or even death. Approximately 100,000 men were arrested under Paragraph 175 (a law in the German criminal code criminalizing homosexual acts between males). Out of those detained, around 50,000 were convicted and many faced imprisonment; while between 5,000 to 15,000 were sent to concentration camps.

After this very traumatic experience, Hans began to question not only the policies but also the ethical foundations of the Nazi ideology. In a letter to his parents from prison, he vowed to become “something great for the sake of mankind.” He was found guilty on June 2, 1938, and was handed a relatively lenient sentence - the state's prosecuting attorney asked for a one-year prison sentence, but the judge decided on just one month, which he counted as time already served.

As Scholl stepped back into the wider world, the next chapter of his life was about to kick off - a shift from being passive to standing up. At the University of Munich, where he would find others who shared and reinforced his growing political disillusionment, the atmosphere was tense, as if something was simmering, ready to boil over and trigger a full-scale rebellion.

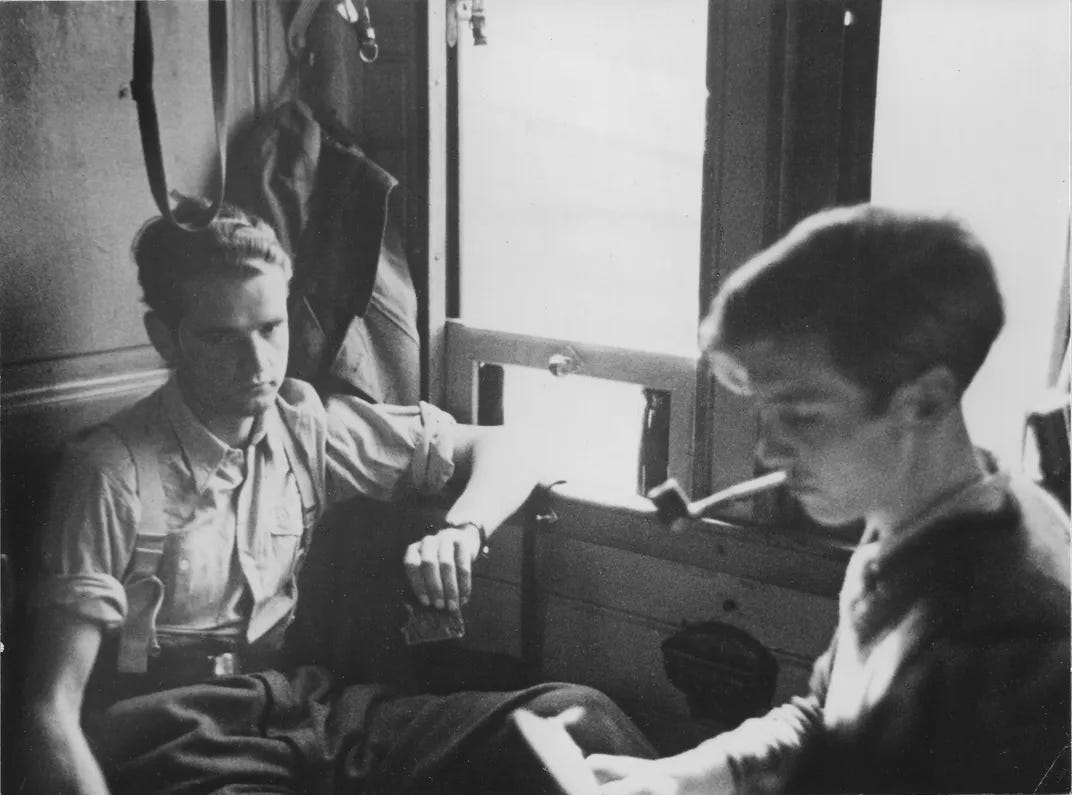

During the chaotic wartime, all young male medical students not only underwent basic military training but also got trained as medics. In 1937, Hans, Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, and their colleagues from the University of Munich were among those ordered to the Eastern Front. It was there, amidst the violence and carnage of war, that reality hit them hard, chewing their convictions before casually spitting them out onto the blood-soaked earth. The young students witnessed the horrible atrocities done by SS forces against Jewish civilians, including harsh beatings, abuse, and the unrelenting persecution that defined the Nazi regime. They saw entire communities being torn apart and destroyed, and within the cramped ghettos, came in contact with the sorrowful gaze of starving children and the anguish of parents unable to protect their families. Following a visit to the Warsaw Ghetto, Hans wrote in a letter to his parents: "Warsaw would sicken me in the long run (...); Half-starved children lie in the streets, whimpering for bread... The prevailing atmosphere is universally filled with foreboding." To his sister Anneliese, Willi Graf wrote: "I wish I had been spared the view of all this which I had to witness".

This brutal exposure brought an irreversible transformation in Hans Scholl and his friends. There was only one sentiment resonating within the group: they couldn't just stand by and watch anymore. They knew they had to take action, and they had to do it immediately.

Upon their return to Munich, their determination was unwavering. They understood the risks associated with what they were planning to do, but couldn't care less.

"I knew what I took upon myself and I was prepared to lose my life by so doing." - Hans Scholl

“Nothing is more shameful to a civilized nation than to allow itself to be “governed” by an irresponsible clique of sovereigns who have given themselves over to dark urges – and that without resisting.”

Leaflets. This was their method of resistance. Simple yet powerful, these pieces of paper became the voice of Hans Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, and their expanding circle of allies within the University of Munich. Scholl and Schmorell were usually the main authors, but the entire group participated in discussions and decisions about the content and the message they wanted to convey. Preparing this material was a lengthy process that involved late-night typing sections and the use of mimeographs to produce copies. Basically, the operation was complicated, and it was really challenging to keep it a secret.

One of the most powerful paragraphs of this first leaflet reads:

"If the German nation is so corrupt and decadent in its innermost being that it is willing to surrender the greatest possession a man can own, a possession that elevates mankind above all other creatures, namely free will – if it is willing to surrender this without so much as raising a hand, rashly trusting a questionable lawful order of history; if it surrenders the freedom of mankind to intrude upon the wheel of history and subjugate it to his own rational decision; if Germans are so devoid of individuality that they have become an unthinking and cowardly mob – then, yes then they deserve their destruction."

Sophie Scholl, upon learning of her brother's and his friends' activities, was immediately drawn to the cause. Although Hans was hesitant at first, he eventually agreed to let her join the group. Christoph Probst also joined them around this time.

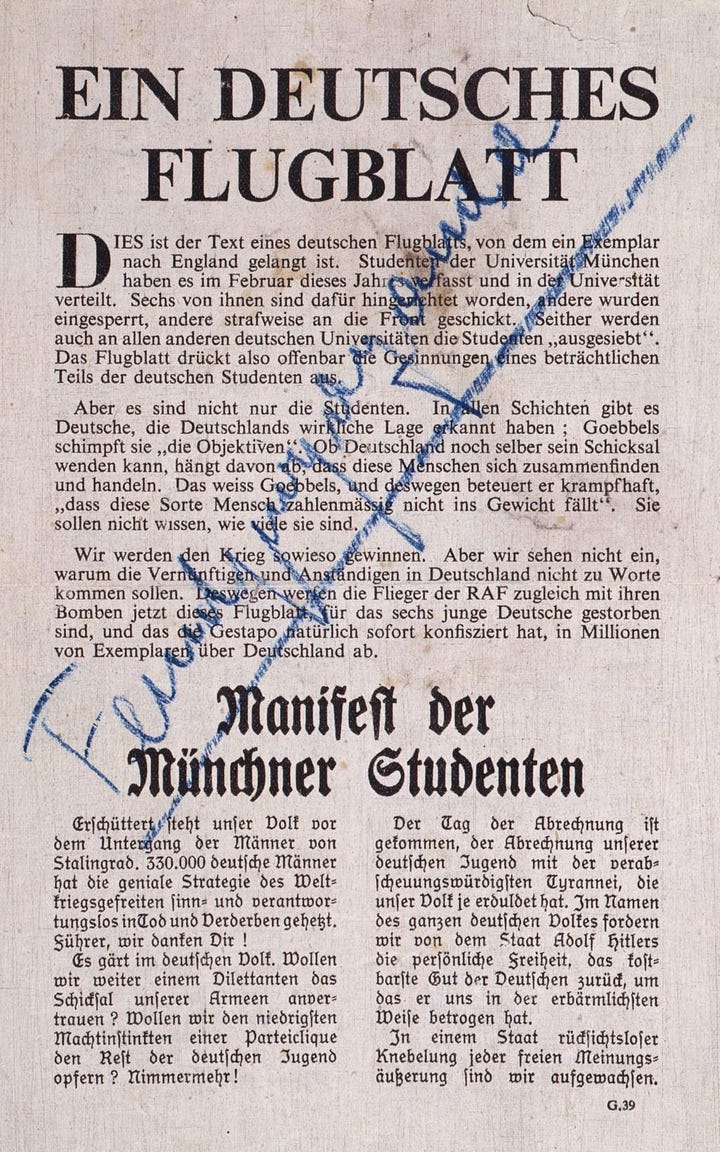

By the summer of 1942, escalating in urgency and audacity, four of six leaflets had already been written. Initially, a decision was made to distribute them via mail, targeting an intellectual audience that included other universities, professors, booksellers, authors, and friends. The members of the White Rose went through phone books to find names and addresses, hand-writing each envelope. Over time, they started to leave copies in public places such as telephone booths and post offices. At the bottom of each document, readers found an urgent call to action: "Please make as many copies of this leaflet as you can and distribute them."

“Every word that comes from Hitler's mouth is a lie.”

As the Second World War progressed, Germany started encountering more and more challenges. At that point, the White Rose understood the crucial moment they were in. Their fifth pamphlet, "Aufruf an alle Deutsche!" ("Appeal to all Germans!"), produced in 6,000-9,000 copies, marked a bold escalation in an explicit call for direct sabotage of Hitler's war machine. "And now every convinced opponent of National Socialism must ask himself how he can fight against the present ‘state’ in the most effective way…"

In January 1943, Germany faced a major setback with a tough loss at the Battle of Stalingrad, which forced a big change in the war's direction. The German people, who were previously uplifted by early triumphs, were now grappling with the harsh realities of defeat and destruction. In response to this, the White Rose intensified their activities. At the same time, tensions at Munich University reached a fever pitch, when Nazi Party official Paul Giesler made inflammatory remarks that insulted the students, particularly the women. On February 4, 8, and 15, a bold form of quiet rebellion emerged, with slogans like "Down with Hitler!" and "Freedom" appearing painted on public buildings all over Munich. This action clearly indicated that the White Rose's influence was motivating more than just passive resistance.

As the official news of the defeat at Stalingrad spread across Germany, the White Rose wrote their sixth and final leaflet:

"Even the most dull-witted German has had his eyes opened by the terrible bloodbath, which, in the name of the freedom and honour of the German nation, they have unleashed upon Europe, and unleash anew each day. The German name will remain forever tarnished unless finally the German youth stands up, pursues both revenge and atonement, smites our tormentors, and founds a new intellectual Europe. Students! The German people look to us!”

“Somebody, after all, had to make a start."

On that tragic February 18, 1943, Hans and Sophie took it upon themselves to distribute the material at their university. As fate would have it, this would mark the beginning of the end for the White Rose. Because Jakob Schmid, after witnessing the papers flying through the university hall, made the fateful decision to report the young siblings to the authorities.

Hans and Sophie were arrested on the same day. In Hans's bag, the Gestapo found the draft for a seventh pamphlet, which led to Christoph Probst's arrest in Innsbruck on February 20. In the following days, over eighty individuals across Germany were arrested too. Some faced execution, while others were sent to concentration camps, as Heinrich Himmler invoked the brutal policy of 'guilt by relation'.

By February 22, the stage was set for a spectacle of injustice in Munich's People's Court. The trial, if you could even call it that, was pretty much a done deal. Presided over by Roland Freisler, a judge infamous for his zealous prosecution, it was a mockery of the judicial process, lasting barely four hours. Freisler, baffled by the audacity and courage of these young individuals, questioned what had "corrupted" them. Sophie Scholl didn't hesitate to reply: “Somebody, after all, had to make a start. What we wrote and said is also believed by many others. They just don’t dare to express themselves as we did. You know that war is lost. Why don’t you have the courage to face it?”

On the same day, Hans Scholl, Sophie Scholl, and Christoph Probst were sentenced to death for high treason. In a final exchange, Freisler asked Sophie as the closing question whether she hadn’t “indeed come to the conclusion that [her] conduct and the actions along with [her] brother and other persons in the present phase of the war should be seen as a crime against the community?”, to which she answered: “I am, now as before, of the opinion that I did the best that I could do for my nation. I therefore do not regret my conduct and will bear the consequences that result from my conduct.” On the back of her indictment, she wrote the word "Freedom".

A few moments later, the three were escorted to the guillotine. Sophie, with a courage that never wavered, went first. While historical records offer varying descriptions of her final words, many affirm that it was "Die Sonne scheint noch" (The sun still shines). Following her was Christoph Probst, who shouted, "We will meet each other in a few minutes!" Lastly, Hans sealed their fate with a resounding declaration of resistance, "Long live freedom!"

We will not be silent. We are your bad conscience. The White Rose will not leave you in peace!

In the wake of the executions of Hans and Sophie Scholl and Christoph Probst, the brutal machinery of the Nazi regime did not stop. Willi Graf, Alexander Schmorell, and Kurt Huber were arrested and later executed. The group's wider circle, including friends and supporters, was subjected to the relentless scrutiny and retribution of a regime that tolerated no dissent. But the end of their lives did not mark the end of their message or the influence they would have on history.

Following the end of the war, Germany and the world started recognizing and honoring the bravery and sacrifice of the members of the White Rose. They were remembered through the erection of monuments, the naming of streets and schools in their honor, and the adaptation of their story into films, books, and plays. The recounting of their journey has become an important part of German resistance history taught in schools, and museums and educational programs dedicated to their memory ensure that their message continues to inspire those who seek justice and freedom. The University of Munich, where everything began, houses a permanent exhibition dedicated to their memory.

After the first executions were carried out and news reached the public, Hans Leipelt and Marie-Luise Jahn, students at the Chemical Institute of Munich University, typed out several copies of the White Rose's sixth leaflet, and entitled it: “…and yet their spirit lives on!”

Their assertion couldn't have been more accurate. The spirit of the White Rose truly lived on, it still lives on, and it will continue to live on… forever.

This is where Substack scores above all other media platforms. I come across excellent writing on a topic that perhaps I wouldn't have chosen to read, but which I should and must read, and which resonates so strongly with my family experience. Thanks for posting this and for broadening my knowledge of Germany's past.

I loved this! I'm working on a story that takes place during all of this...and yet I knew nothing about it. But! And this is a big BUT, it showed me where I had to go to end my story. Thanks for putting this up!