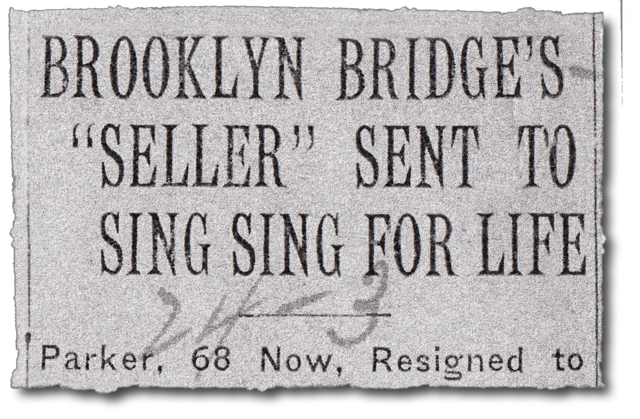

The Scammer Who Sold The Brooklyn Bridge Over and Over Again

In the 1900s, George C. Parker mastered the art of selling New York landmarks that he didn't own

In the late 19th century, New York City pulsed with potential and promise. Carrying just a suitcase and perhaps an address scribbled on a piece of paper, immigrants arrived by the thousands every day, seeking a new beginning in this "land of opportunity". Many came from Europe, particularly Italy, Ireland, and Germany; some fleeing economic hardship, others political chaos, but every single one of them motivated by the dream of a better life. Yet, the reality they faced in New York was starkly different from their optimistic expectations. The city presented a harsh reality of discrimination, overcrowded tenements, scarce employment, and the challenges of trying to figure out how to assimilate a culture that was so foreign to them.

The Lower East Side of Manhattan became a symbol of this immigrant experience, packed with tiny apartments where families would squeeze in together or even bunk up with other families, poor health and sanitary conditions, and little to no clean water. Nearly half of the city’s deaths by fire took place there. (I'd highly recommend you check out Jacob Riis’ book, How the Other Half Lives if you want to learn more and see more pictures). Despite the challenges, these areas blossomed into cultural hotspots, presenting an awesome mix of languages, food and traditions. In this context, communities came together and formed a strong support network through their local churches, synagogues, and hangout spots. And as more people poured in, this neighborhood became a core part of the vibrant and diverse mix that is New York's society.

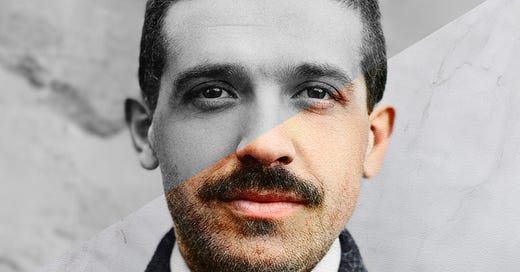

Amidst all this, there were those who sought to exploit the dreams and vulnerabilities of the newly arrived. One man in particular, George C. Parker, was especially good at it. He might have seemed like any other wealthy New Yorker to anyone passing by. But to those who paid a bit more attention and looked closer, he was something else: a master of illusions and a seller of dreams. And by "dreams" I basically mean the Brooklyn Bridge. Except, of course, that he didn't actually own it.

But, hey, guys, that's just one tiny, inconvenient detail. Who cares.

This was Parker's most successful scam, one he executed several times a week, for over forty years (or so he claimed).

George C. Parker was born in 1860 to Irish immigrants in New York City. His early life's pretty much an enigma, but there are two things about him that we know for sure: Parker knew how to charm. And he was a huge scammer who made a living out of lying, deceiving and exploiting people.

The Brooklyn Bridge wasn't selected by accident. Despite not being directly on the route for ships bound for Ellis Island, it has always been a towering symbol of New York. More importantly, it served as a crucial link between Manhattan and Brooklyn, bustling with thousands of pedestrians, workers, and travelers daily.

To pull off his audacious scam, the strategy was simple. Always impeccably dressed, Parker would first score the area and look for a target. After that was done, he would approach the victim, usually an unsuspecting immigrant, and introduce himself as a successful business owner with a seemingly harmless opportunity: the chance to operate a toll booth on the Brooklyn Bridge, which, at the time, did indeed charge pedestrians, horse riders, and vehicles various fees to cross. According to NYC Walks, crossing the bridge on foot was just a penny, while a horse and rider were charged 5 cents, and a horse and a cart cost 10 cents. Bringing farm animals across involved a fee of 5 cents per cow and 2 cents for each sheep or pig.

Parker would smoothly change the narrative once he had gauged his victim's interest and assessed their financial situation. Sometimes, the job offer would evolve into an opportunity for a business partnership, where he would suggest that the individual could not only operate but also co-own the toll booths on the bridge. He would escalate even further for those he thought could afford to spend even more, introducing the idea that the Brooklyn Bridge itself was for sale and that the victim could become its sole owner, control all toll operations, and make huge profits.

This flexibility ensured that he could extract as much money as possible from each victim, selling them not just a job or a partnership, but the dream of owning a piece of America.

The “Big Bridge”

After 14 years of construction and numerous setbacks, the Brooklyn Bridge was finally completed in 1883. It was the world's first steel-wire suspension bridge and, at the time, the longest of its kind, stretching across the East River for 1,595 feet.

Sadly, approximately 27 unfortunate souls lost their lives in the process of building it. The risks came from multiple sources: the crazy heights, the bends suffered by the men working in compressed air under the river, and the general 'oops' moment that 1800s workplace safety could provide.

I mean, what the f*ck:

Anyway. After all that smooth-talking, Parker would go on to negotiate, adjusting his asking price based on what he believed the victim could pay, ranging from $75 to as much as $50,000—equivalent to about $1.8 million today. And then, off he went - with his pocket full of money, chuckling at the ease with which he'd managed to turn New York's iconic bridge into his personal gold mine, and ready to do it all over again.

Meanwhile, the poor victims proceeded to do the most obvious thing: make use of their newfound property. Driven by Parker's convincing scheme, some went as far as attempting to set up toll booths on the bridge, genuinely believing they were entitled to collect fees from the people who crossed daily. This move, however, quickly attracted the attention of the authorities. But the scene of individuals claiming ownership of the Brooklyn Bridge was so bizarre that the officers didn't know how to react initially. All they could do was shut down the unauthorized toll booths and send those running them, who were basically treated as crazy individuals trying a very bold kind of scam, to jail. It wasn't until a pattern emerged, with multiple "owners" presenting similar stories, that the authorities realized what was happening and took proactive measures to prevent further scams, putting signs around the landmark that declared in clear terms that it was not for sale.

This move effectively ended Parker's real estate career, at least in the bridge-selling business. After all, he still had Ulysses Grant's mausoleum, the Madison Square Garden and the Metropolitan Museum of Art tucked away in his portfolio, ready for the next "sale."

Despite all his fraudulent activities, Parker managed to evade capture for years. Only in 1928, after a life of cons and a final bad check, did the law catch up with him. He was sentenced to mandatory life imprisonment at Sing Sing Prison for fraud, where he spent the last 8 years of his life.

“If you believe that, I have a bridge in Brooklyn to sell to you.”

This is how today's story ends.

But let it be a reminder to us all - when the deal seems too good to be true, maybe, just maybe, there's a "bridge" in that sales pitch. But if you're ready to take advantage of such an opportunity, well, I've got some oceanfront property in Arizona to throw in as a bonus.

We must also appreciate the fact that Parker pulled off his scams long before anyone had ever dreamt of an internet. By comparison, that Nigerian prince (you remember him -- the guy who offers half of his escrowed millions for a measly contribution) is crude and pathetic.

Now we know the rest of the story, from that famous quote.

Good to see you back, Marina.

Always enjoy your writing- and your photographs.