Letter from Ellis Island

Last week I visited what was once the most important gateway to America

I just came back today from a 10-day trip to New York City. It was a lifelong dream of mine. Something about the way I used to imagine the wonderful chaos that goes on through the streets of that city always made me feel compelled to visit it one day. Like almost any non-American person who grew up watching Hollywood productions, I had this fantasy that I would be able to wander around the streets with my Starbucks cup in hand, getting to know the locals and basically mimicking a scene from Sex and The City. The reality was very different (and much better), of course.

But chaos wasn’t the only thing I found in New York. While making my travel plans, I made sure that I was going to have enough time to hop on a ferry that would take me through the waters of the Hudson River to Ellis Island - the historical site, now a national museum, that served from 1892 until 1954 as an immigration station (then America's largest and most active one) and a symbol of hope for the approximately twelve million immigrants who passed through its doors. The first person to be processed there was 17-year-old Annie Moore from Cork, Ireland - one of the 700 people arriving on the opening day on January 1, 1892.

Here's a comparison between a photo taken somewhere between 1902 and 1913 that I colorized last year, and the same room today, in a photo that I took last week.

This is the Registry Room (also known as the Great Hall because of its large size), the room where immigrants had to wait their turn for processing by immigration officials. Thousands of people were processed every day, and the waiting time could be long; on average, approximately 3 to 7 hours.

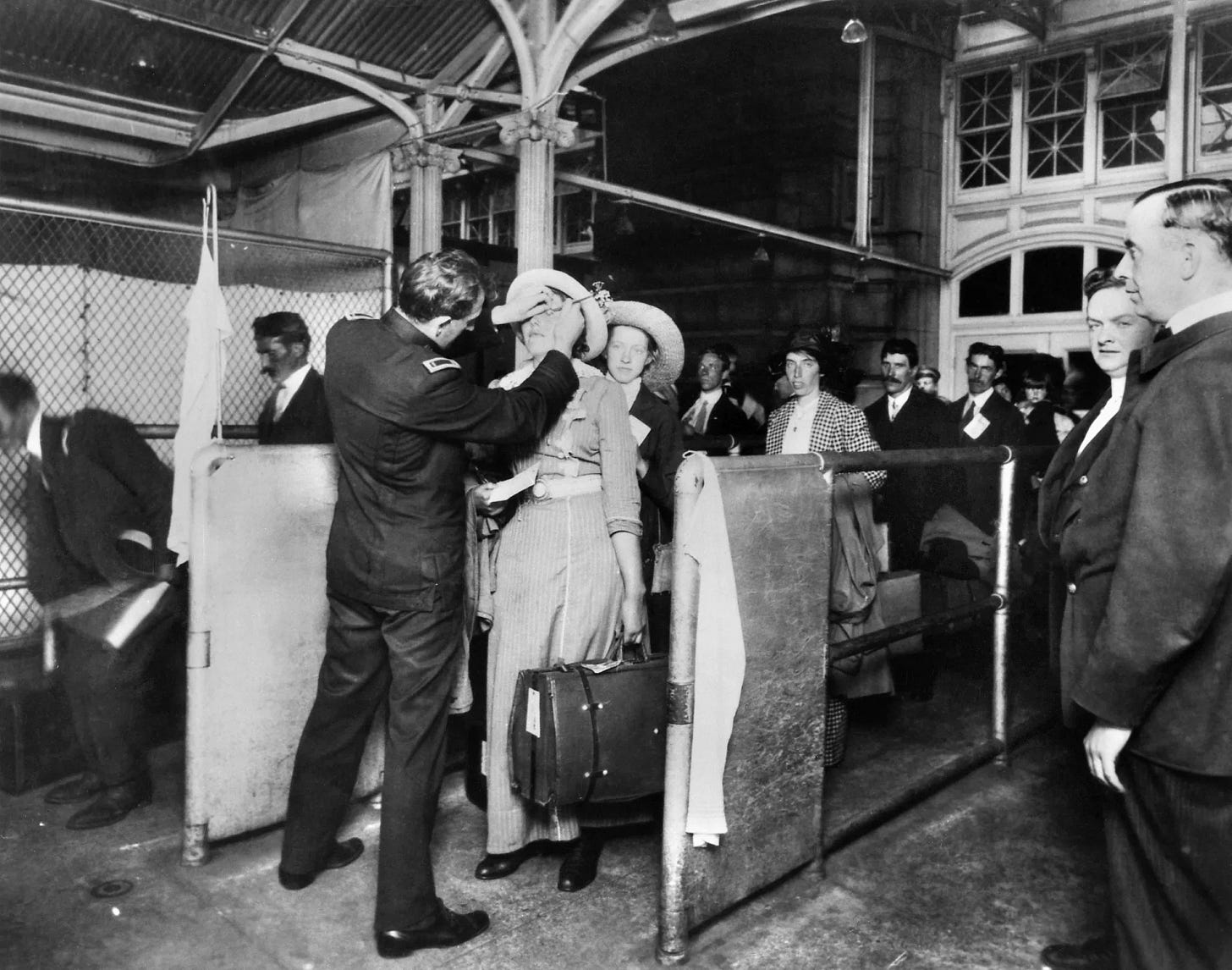

The medical inspection was a crucial part of the entire process. Doctors stood on this room looking for people who were having difficulty walking or breathing, or who exhibited any other health issues. Those who were deemed unwell or unfit were sent to the Contagious Disease hospital. These scans were known as "six-second physicals."

As per published by PBS: “When Ellis Island opened its doors in 1892, there were six physicians stationed to inspect the more than 200,000 immigrants who streamed through that year. By 1902, there were eight physicians examining more than 500,000 arrivals; by 1905, 16 doctors examined 900,000 immigrants. In 1916, there were 25 physicians and four inspection lines were running simultaneously.”

By 1916, it was claimed that a doctor could diagnose a variety of medical conditions simply by looking at an immigrant.

Dr. Henry M. Hurd, the superintendent of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, expressed his concern: “how can a physician inspect 2,000 persons as they should be in a couple of hours, when it sometimes takes a doctor twice that long to diagnose one patient?”

It was at this point that many individuals had all their hopes and dreams crushed. For some, Ellis Island was the “Island of Hope”, while for others - like those who had their entry into the country denied or for the families who were separated - it became the "Island of Tears".

Journeying by Ship to the Land of Liberty

“(…) First and second class passengers who arrived in New York Harbor were not required to undergo the inspection process at Ellis Island. Instead, these passengers underwent a cursory inspection aboard ship, the theory being that if a person could afford to purchase a first or second class ticket, they were less likely to become a public charge in America due to medical or legal reasons. The Federal government felt that these more affluent passengers would not end up in institutions, hospitals or become a burden to the state. However, first and second class passengers were sent to Ellis Island for further inspection if they were sick or had legal problems. This scenario was far different for "steerage" or third class passengers. These immigrants traveled in crowded and often unsanitary conditions near the bottom of steamships with few amenities, often spending up to two weeks seasick in their bunks during rough Atlantic Ocean crossings”. Read More

Augustus Sherman

The photographs below, most likely of detainees wearing their folk costumes who were waiting at the island for many different reasons - not only medical, were taken by amateur photographer Augustus Sherman, who worked as the Chief Registry Clerk on Ellis Island from 1892 until 1925.

Seeing the originals on the walls during my visit reminded me of this colorization project that I did with some of the pictures in 2019. You can see more of them here.

In 2005, a book was published, featuring several more of Sherman’s striking portraits.

After 1924, Ellis Island was primarily utilized as a migrant detention center, being declared by President Lyndon Johnson part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1965. Following the closing of the immigration station, the buildings sat vacant for several years before being partially opened to the public in 1976, undergoing a major renovation project in 1990.

Today, the museum receives almost 2 million visitors annually.

Recommended reading: