"The Freaks": How Two Kidnapped Albino African-American Brothers Were Forced into Circus Stardom

The Muse brothers' tale of survival within the abusive freak show industry

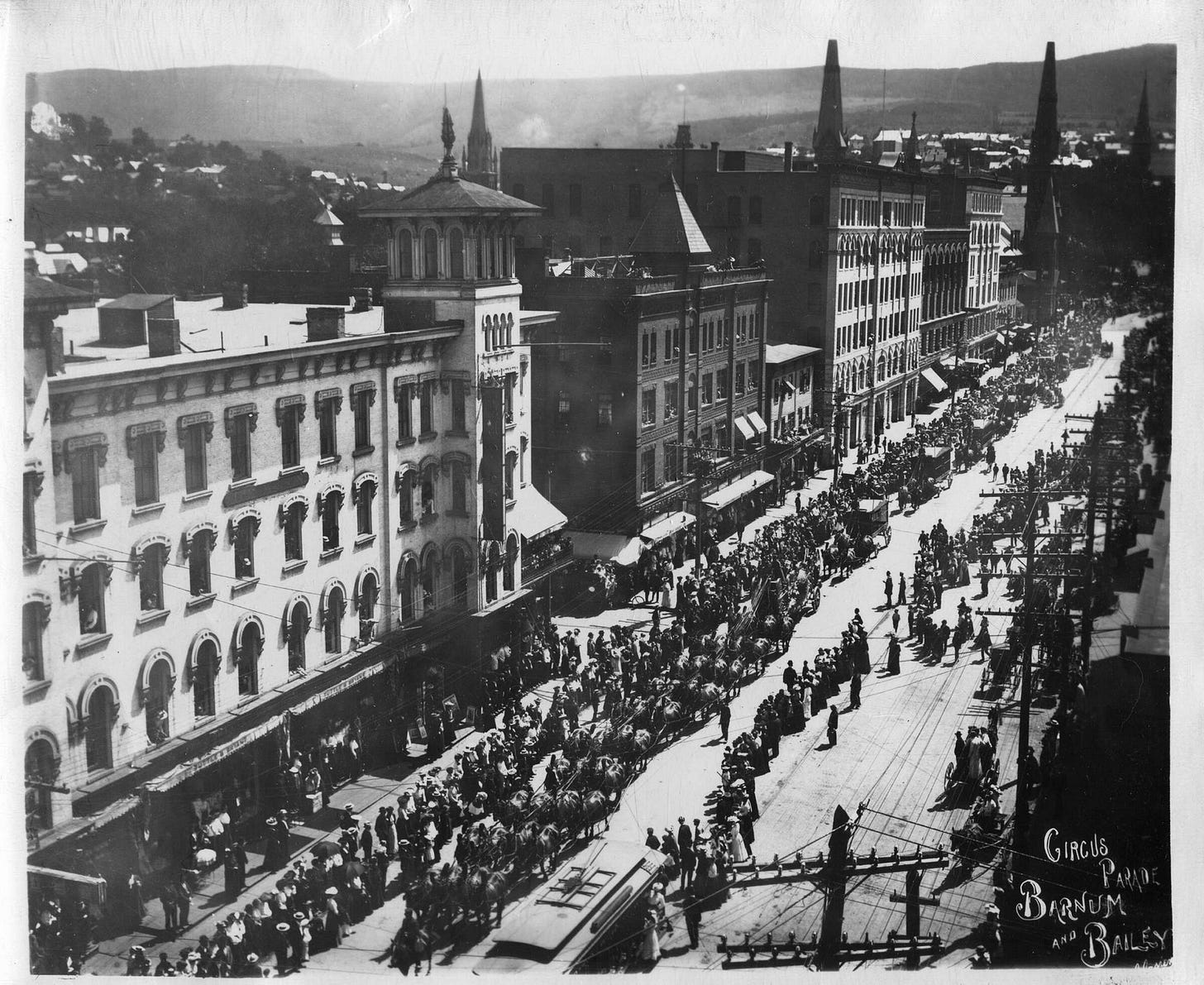

As the 1900s rolled around, circuses started to explode on the American entertainment scene. Forget radio, TV, or movies - they weren't a thing yet. Instead, it was all about the thrill of insane acrobatics, wild animals, and exciting performances that took over people's imaginations. These spectacles were a major event and an eagerly anticipated break, particularly in remote and rural areas where life could be repetitive and dull. For many people at this time, their knowledge of different cultures or unusual creatures existed primarily within stories told around fireplaces or articles read under candlelight. But when the big top rolled into town, it brought pieces of the world to their doorsteps. It didn't matter who or where you came from; almost everyone was swept up by the magic.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were marked by dramatic changes on every continent. Europe saw empires teetering precariously due to major political upheavals while the Industrial Revolution rattled established new norms and ways of life. Asia, too, wasn't untouched by this wave of transformation, as ancient dynasties grappled with burgeoning nationalism and modernization forces. At the same time, Africa and Latin America were dealing with the complex implications of colonial power and the start of movements toward independence. This worldwide panorama of progress, tension, and change set up an exciting stage for the dawning century. It signaled an era where old customs would gradually fade into obscurity, marking the birthplace of our modern times.

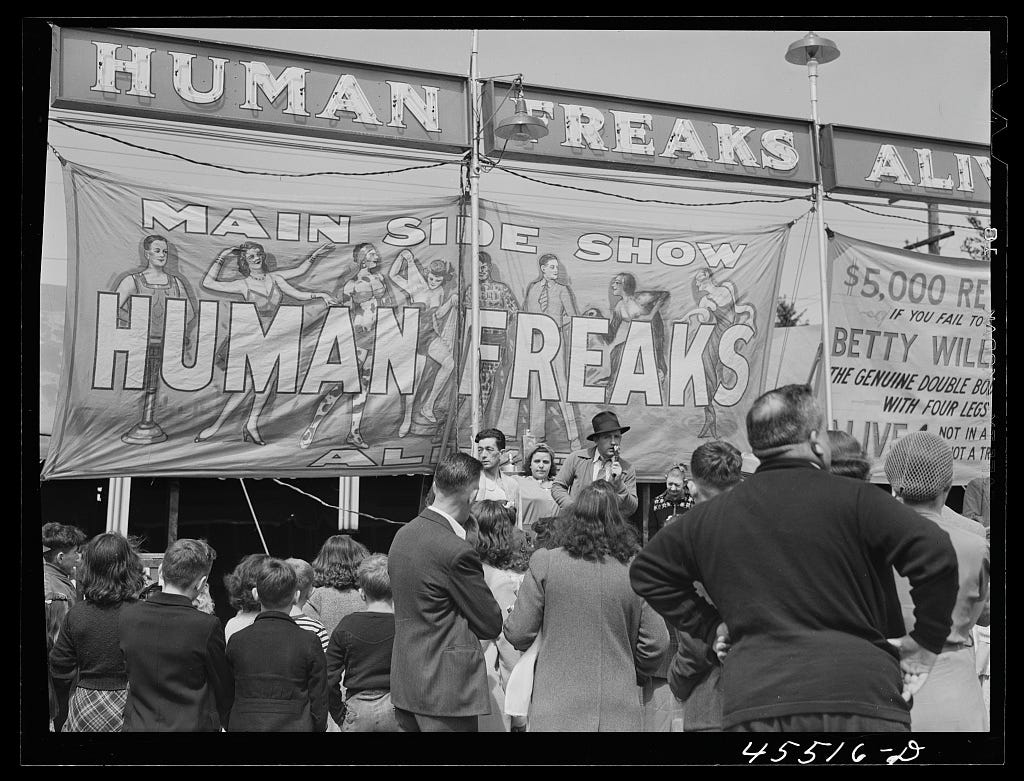

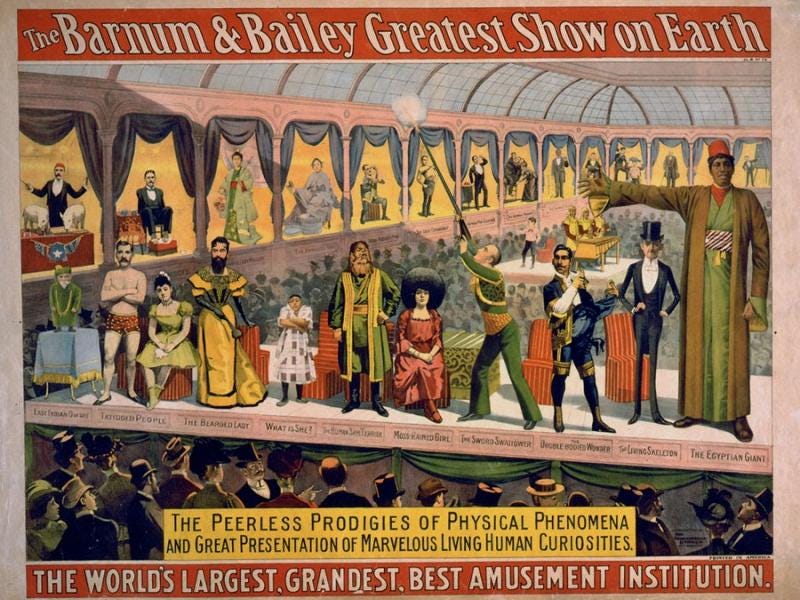

But not every aspect of life or every group of people embraced this idea in the same way. In the circus world, it was beginning to gain force a peculiar and controversial niche where people with unique physical attributes (often due to rare genetic conditions) became the main attractions. In this setting, and made explicit by their stage names (such as The Living Skeleton, The Four-Legged Woman, The World's Ugliest Woman, Lionel The Lion-Faced Man, and Three Legged Wonder), their uniqueness was not only displayed but also mocked, sensationalized and capitalized upon.

The phenomenon, known as a "freak show," gradually grew to be as much a part of the circus identity as the acrobats and clowns. Far from progress, this was classic old-school exploitation wrapped up in shiny showbiz.

“I think we all need to own a little raw piece of this history. And to own it, we need to understand it and acknowledge it.” ― Beth Macy

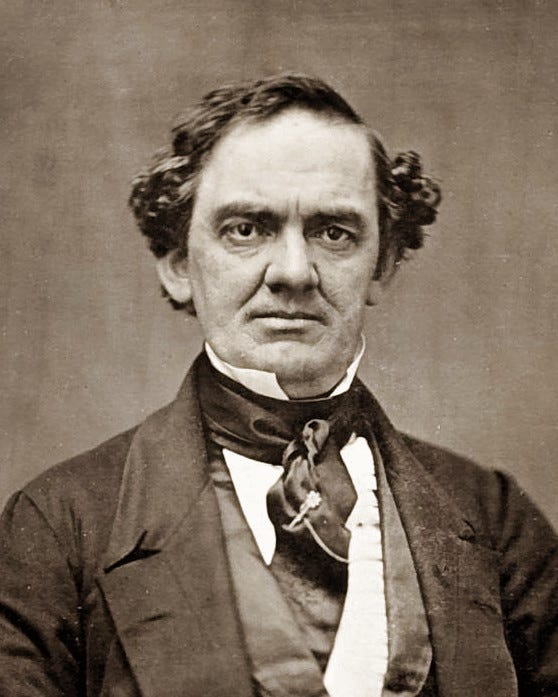

This industry owes its rise mainly to the megalomaniac vision, wild imagination, mass manipulation skills and - why not - the questionable character of one man: Phineas Taylor Barnum, who ignited the "Golden Age" of freak shows. (If his name rings a bell but you can't quite place it, think of Hugh Jackman's toe-tapping, top-hat-wearing portrayal in 'The Greatest Showman.')

Barnum was a visionary in the realm of public entertainment. In 1841, he acquired Scudder's American Museum in New York City and transformed it into Barnum's American Museum. This wasn't your average museum, though - it was more like an all-in-one zoo, lecture hall, freak show venue, wax museum, and theater. Its appeal resided in its constantly evolving collection of performances and exhibits thoughtfully curated to guarantee that visitors, for a mere twenty-five cents the admission, would consistently discover something different and exciting with every visit. In this amazingly quirky wonderland, you'd have a tough time finding a boring moment, as there were plenty of eyebrow-raising things going on to keep you entertained. Dioramas or scientific instruments might greet you one day while on another day, perhaps a flea circus or even a tree trunk supposedly linked with Jesus' disciples might keep you occupied. Glass blowers at work alongside taxidermists and phrenologists were pretty common sights.

The main attraction was the infamous and hideous Fiji Mermaid exhibit – a creature that really just looked like someone sewed together parts of a mummified monkey torso with a fish tail but Barnum sold it as legit - and people believed him. It was an instant sensation.

“The story goes like this: P.T. Barnum came across the remarkable tale of an eminent British naturalist by the name of Dr. Griffin who had obtained the remains of a real mermaid. Barnum approached this man of science and attempted to convince him to display this wonder, but came away empty handed until an eager public demanded their opportunity to inspect this curiosity of the seas. Barnum and this Dr. Griffin ultimately capitulated to public enthusiasm and opened the doors for one week in New York City, and the crowds descended. In truth, the half-monkey, half-fish gaff was the property of Moses Kimball, Barnum’s one-time rival and later associate, and the so-called Dr. Griffith was in fact a persona adopted by another of Barnum’s associates by the name of Levi Lyman. The mermaid most likely originated from Japan where it had been purchased and brought back to the United States by a fisherman, from whose son Kimball finally purchased it.” Source

The collection of animals varied wildly from exotic beluga whales swimming around in an aquarium tank right down to elephants, lions, and tigers making guest appearances now and then. Adding icing on the cake were performances by ventriloquists and magicians and a “pretty babies” contest.

It was nothing short of a sensory and intellectual overload. The improbable was not just possible there, but likely sitting next to you, enjoying a bowl of oysters at the museum's bar.

Charles Sherwood Stratton, an American with dwarfism better known by his stage name, General Tom Thumb, was Barnum's first major "human attraction." Tracked down at just five years old, Stratton's talents in singing, dancing, mimicking, and impersonating famous personalities like Napoleon Bonaparte became sensational events that elevated him to international celebrity status. To exhibit young Charles in New York, Barnum struck a deal with his father, a local carpenter, paying him three dollars per week. Once in New York, the showman started marketing Stratton as an English lad, brought to America with a hefty price tag. He also claimed that Charles was eleven years old, a detail that made his tiny size all the more unusual.

Barnum again demonstrated his knack for storytelling in the infamous Cardiff Giant hoax. The story began in October 1869, when a ten-foot-tall figure, purported to be a petrified prehistoric man, was 'discovered' on a farm near Cardiff, New York. In reality, the figure was a carefully sculpted gypsum statue, secretly buried and later 'unearthed' to create a sensation. George Hull, the mastermind, had commissioned a sculptor to carve the "artifact" and then buried it on his cousin's farm, hoping to "discover" it a year later and make big bucks by showcasing this 'discovery' across America. PT Barnum, always eager to embrace every opportunity for profit, proposed to buy the Cardiff Giant from Hull for $50,000. Upon his refusal, Barnum created a replica and declared the original fake. The facade crumbled in December when Hull openly admitted to the hoax.

P.T loved a sensational story and always took advantage of every opportunity to craft one for his exhibits, knowing that these tales would draw more attention and awe from his public. While undeniably effective and successful, this approach to showmanship has raised many questions about his character and ethics, but he remained unperturbed and even seemed to revel in them. "The bigger the humbug, the better people will like it.", he once said. The ludicrousness of the stories he created didn't matter; they served their main purpose: keeping audiences hooked and stirring emotions within viewers, which kept them coming back for more.

"Without promotion, something terrible happens... nothing!"

The story of Joice Heth, notably the first well-documented case of an African-American being exploited in the setting of freak shows, is one of Barnum's most deplorable moves, and it shows the lengths he would go to build his showbiz empire.

Sold to Barnum by her enslaver in Kentucky in 1835, Joice was a frail woman in her 70s, nearing blindness and pretty much paralyzed - a vulnerable figure in every sense. Yet, when Barnum laid eyes on her, he didn't see an elderly woman in need of care but saw something far more compelling instead: dollar signs and a chance to wow people. For that, he spun a tale around her, claiming she was 161 years old and had been the nurse to none other than George Washington, America's first president. Barnum went as far as getting rid of all of her teeth in one cruel attempt to make her look older.

Joice was taken around the country, where she would deliver stories about “little George”. Posters advertising her ‘act’ boasted with grandiosity: “Joice Heth is unquestionably the most astonishing and interesting curiosity in the World! She was the slave of Augustine Washington, (the father of Gen. Washington) and was the first person who put clothes on the unconscious infant, who, in after days, led our heroic fathers on to glory, to victory, and freedom. To use her own language when speaking of the illustrious Father of this Country, 'she raised him.'"

Needless to say, Joice Heth did not serve as the centenarian nurse to any president, much less George Washington. In truth, she was a woman who endured a life of exploitation, a harsh reality from which she could not escape even in death. In 1836, after her passing, Barnum orchestrated a public autopsy, charging spectators 50 cents each for admission. This morbid and degrading spectacle revealed that Heth was approximately 80 years old. Initially, Barnum attempted to shift the blame onto her, accusing her of "lying about her age." However, he later confessed that it was all a hoax—a rare moment of admission amidst a career filled with deception and half-truths.

Exploring human bodies for amusement and profit

People born with physical disabilities faced a tough world back then. It was a time when society, driven by fear and ignorance, often rejected those who weren't seen as 'normal' (not that it has changed much since then), and medical understanding of various conditions was rudimentary at best, which led to widespread stigmatization. For many, this meant a life on the fringes, with few opportunities for employment or social integration. Those without family support had an even more challenging time, spending their lives usually confined in asylums. These institutions, far from being places of care, were more like prisons, where neglect and abuse were common, and living conditions were often deplorable.

Paradoxically, in this bleak scenario, the freak show emerged as an unlikely refuge, providing a platform to earn a living for those who had no other options. It was there that the men and women who faced rejection and isolation in the broader society sometimes found a semblance of belonging and community among others similarly ostracized, and maybe even got to achieve a certain level of fame. However (and it's important not to lose sight of this), such experiences belonged only to a select few among these performers. The majority endured degrading conditions under exploitative management, which capitalized on their differences for profit without any regard for their wellbeing. The fundamentally abusive nature underlying these shows can't be dismissed just because there might have been rare instances of personal success stories resulting from them.

During this period, a new force in the circus world emerged: the Ringling Bros. Circus, founded by five brothers — Albert, Otto, Alfred, Charles, and John — in 1844 in Wisconsin. Their enterprise stood as a strong rival to Barnum's, sparking fierce competition.

In 1907, in a buyout that flipped a page in circus history and fused two of the era's most influential entertainment giants, the Ringling brothers acquired the Barnum & Bailey Circus for an impressive $400,000 — a monumental sum at the time, equivalent to approximately $13 million today.

Separate Is Not Equal

In the early 1900s, Truevine, Virginia, was a living reminder of the post-Civil War South, a place where shadows of slavery still lingered in both the fields and the daily lives of its residents. Unlike other parts of the United States, where factories and cities were booming, Truevine remained deeply rooted in tobacco farming—a labor-intensive crop with immense historical and economic significance for the region. The very earth of this small town seemed soaked with the sweat, blood, and tears of the African-American families who toiled upon it. For most of their descendants who still called this place home, things hadn't changed much.

We're talking about a time that was tainted by the harmful rise of Jim Crow laws, which gave legal backing (and encouragement) to racial segregation. For African Americans, this meant inferior schools, transportation, restrooms, and even separate drinking fountains - all marked by "Colored Only" signs that stood like sentinels.

These laws made it nearly impossible for Black citizens to vote due to unjust employed mechanisms like poll taxes (which Black Americans often couldn't afford) and literacy tests, a prerequisite to voting.

Lynching, a brutal form of vigilante justice, was rampant in the South, part of a systemic campaign of terror. According to historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage, Virginia alone witnessed 86 lynching deaths between 1880 and 1930, with African Americans being the primary targets. These victims were accused for various reasons, ranging from severe crimes to minor social infractions or even without any reason at all. One example was the infamous' reckless eyeballing', where a Black person could be punished for merely gazing at a white person with presumed sexual intent.

Within this context of racial tension and struggle for survival, the story of a specific family from Truevine would unravel, revealing a journey that would intersect with one of the most iconic and controversial aspects of American entertainment history.

You guessed it: the circus - particularly the world of freak shows.

“Still, in this remote and tiny crossroads, where everyone knew everyone for generations back, George and Willie Muse were different.” ― Beth Macy

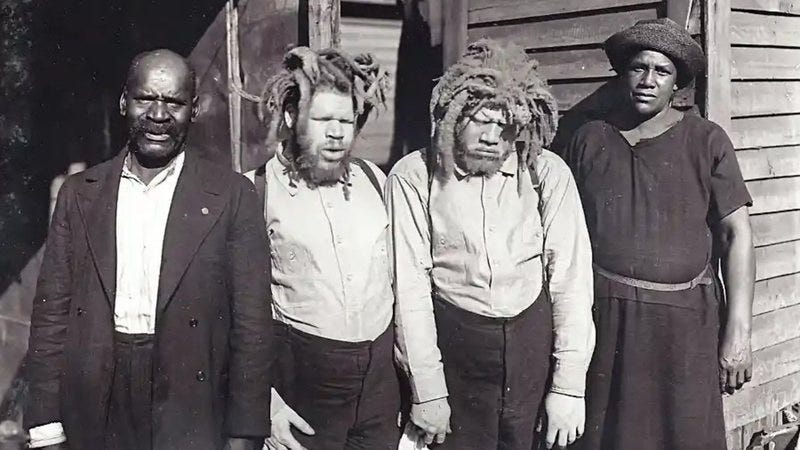

Willie and George Muse, the two oldest siblings in a family of five, were born to Harriett Muse in Truevine. Their unique appearance as people with albinism (a rare, genetically inherited condition characterized by a lack of melanin, the pigment that provides color to the skin, hair, and eyes) born to Black parents added an extra layer of danger to their lives, considering the tense racial climate they grew up in.

Life for the Muse family was no walk in the park. Willie and George got a taste of hard work from a young age, pitching in with sharecropping duties like keeping an eye out for pests in the tobacco rows. But Harriett, a devoted mother, did everything to keep them safe. She would wrap them in cloth to protect their delicate skin from the sun, making sure they wore long sleeves even when it was boiling hot at 100 degrees, and would always step forward to protect them at the slightest hint of danger. However, despite Harriett's unwavering vigilance and care, no one could have anticipated the shocking turn of events that lay just ahead.

It could have been just another day in 1899, but for the Muse family, it was the day that would turn their world upside down.

George and Willie, at the ages of six and nine, were working in the tobacco fields when a circus promoter and "freak-hunter" named James Herman "Candy" Shelton spotted them. As the legend goes, he went on to lure the boys with a piece of candy, and, in the blink of an eye, quicker than a rabbit on the run, the three were gone.

Another version of the story suggests that Harriett initially allowed Shelton to feature her sons in the circus under the assumption that it was a temporary arrangement and that Willie and George would be returned to her once the spectacle was over. Shelton, betraying this agreement, whisked the boys away, effectively transforming what might have been a brief adventure into a long-term kidnapping. We may never really know the complete truth and details behind this abduction, but that doesn't make the cruelty and horror of the incident any less real or terrifying. For Harriett Muse, grappling with the daily struggles of life in a society that already denied her fundamental human rights, she now faced an even more painful horror: the loss of her beloved sons.

Once under Shelton's control, the Muse brothers' lives were upended in ways that defy the imagination. First, to crush their hopes of reuniting with their family, they were falsely informed that their mother had died. Then, they were stripped of their identities and reborn under the stage names "Eko and Iko", complete with titles like "Eastoman's Monkey Men," "Ethiopian Monkey Men," and "Ministers from Dahomey." It was painfully obvious that in this new world they were thrust into, George and Willie's dignity and humanity took a backseat to the spectacle they were forced to create.

Like many others unfortunate enough to find themselves in similar circumstances, the brothers were given outlandish and highly offensive backstories. Far from challenging these fabrications, the media of the era played a willing role in disseminating them. Sensational stories were published in newspapers, including one particularly ludicrous account suggesting that John Ringling had discovered the boys adrift off the coast of Madagascar. Candy Shelton, driven by a relentless pursuit of profit, went as far as to assert that they were the "missing links" between humans and apes.

As "Eko and Iko", George and Willie were forced to perform grotesque stunts such as biting off the heads of snakes and chickens and consuming raw meat, all under the watchful eyes of excited audiences. They were also denied access to education or the opportunity to learn how to read; instead, they were constantly paraded around the United States as part of the circus's traveling shows, never receiving any compensation for their performances despite their significant contributions to the circus's success and the considerable revenue they generated, at times bringing in as much as $32,000 a day.

One day, it was discovered, almost by chance, that Willie and George had an incredible natural talent for music and could play various instruments, such as the banjo, saxophone, and ukulele. Willie, in particular, displayed an extraordinary musical gift. He could listen to a melody once and flawlessly replicate it. Candy Shelton, amazed by these skills, quickly realized the commercial potential and, without wasting any time, incorporated this musical aspect into the brothers' act.

"There's our dear old mother! Look, Willie, she's not dead!"

Harriet never gave up her search for her sons, but in the racially charged climate of the Jim Crow South, her pleas and efforts to locate them were met with indifference and dismissal by law enforcement.

The breakthrough arrived in the autumn of 1927 when a tip led her to a circus that had just rolled into the town of Roanoke, where she was living by this time. Outside the sideshow, a poster proudly presented Willie and George as "ambassadors from Mars" who had been miraculously discovered near a crashed Martian spacecraft in the Mojave Desert. The story suggested that these interstellar travelers had journeyed across the cosmos only to land a gig playing music in a Virginia circus - an unexpected but unique utilization of their extraterrestrial wisdom and technology.

At the bustling Roanoke fairgrounds, Harriet stood out not only due to her determined efforts to push through the crowd but also for being the only Black person in a sea of white faces. Onstage, Willie and George (who were not from Mars, by the way) were playing "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" when suddenly, their eyes landed on that unexpected sight.

It hit George first: the woman they thought had died years ago was alive! And she was right there in front of them. "There's our dear old mother! Look, Willie, she's not dead!" he exclaimed. The brothers' reaction to seeing their mother after such a long separation was immediate and heartfelt. They abandoned their instruments and rushed to embrace her. Instantly, Ringling lawyers and police burst into the reunion. Candy Shelton stepped in, visibly furious, and asserted his ownership over the brothers. But Harriett, she wasn't having any of it. Undeterred by the presence of law enforcement, she took a defiant stand and insisted that she would not leave without her boys. Remarkably, in a region where the Ku Klux Klan wielded significant influence, the police ended up allowing them to go.

Three days later, Harriet, with the help of a local lawyer, made a bold legal move against the Ringling circus, demanding back wages for Willie and George. In response, Shelton filed a counterclaim, alleging that the Muse brothers had breached their contract and caused financial loss to the circus. The ensuing legal battle was a David and Goliath scenario. But against all odds, Harriet, this poor and illiterate woman, a Black maid in the segregated South, took on a powerful entertainment company and came out on top. It was a groundbreaking achievement.

The original kidnapper, Shelton, came back with a new deal. He offered to pay a portion of the brothers' salary to their parents and even employ their other brother, Tom, if Willie and George returned to the circus. By winter 1928, the two were back on tour with Ringling. This time, things went significantly better. They appeared at prestigious venues like Madison Square Garden in New York and were rumored to have performed even at Buckingham Palace.

Over the years, Harriett continued to fight for her sons' rights in court, ensuring fair compensation, a share of their earnings, and regular updates on their whereabouts. When she passed away in 1942, she had bought a piece of land in Franklin County. Her death brought some money to the Muse brothers, and they used it to purchase a house in Roanoke, where they spent their final years, taken care of by family members.

Willie and George continued to grace stages until their well-earned retirement in the mid-1950s. George's journey ended in 1972, while Willie reached the impressive age of 108, passing away in 2001. In a twist that almost seems like poetic justice, he outlived many of those who once exploited him, including Candy Shelton, whom he described as a "dirty rotten scumbag" and a "cocksucker". I mean, who can blame him? It is a genuine epitaph from a man who, after a life full of incredible challenges and against all odds, ultimately got the final say.

I'm coming back next week with my first paying-subscribers-only podcast, where we will dive a little bit more into the lives of some of the people who, like Willie and George, were thrust into the world of the freak shows. Subscribe and stay tuned!

To read more about the Muse brothers’ story, check out “Truevine: Two Brothers, a Kidnapping, and a Mother's Quest” by Beth Macy, available here.

Fantastic piece, I immediately had a flash back of the movie “The Elephant Man”, truly an era where labor unions were needed.

You bring the past to life with your words in the same way as with your coloring of historical photos, enhancing our understanding and appreciation of the humanity behind the images. I’m always moved and awed by your work.