I am bursting with excitement as we wrap up our War Poets series! In just a few days, I'll be setting off on an incredible journey with Leger Holidays, visiting places where the echoes of Sassoon, Owen, Graves and so many others still linger. For those of you who've been following this series closely, I promise to bring this experience to life for you, as I'll be sharing everything in real-time on my Twitter, Instagram, and here on Substack. So, no matter where you are, you're welcome to come along!

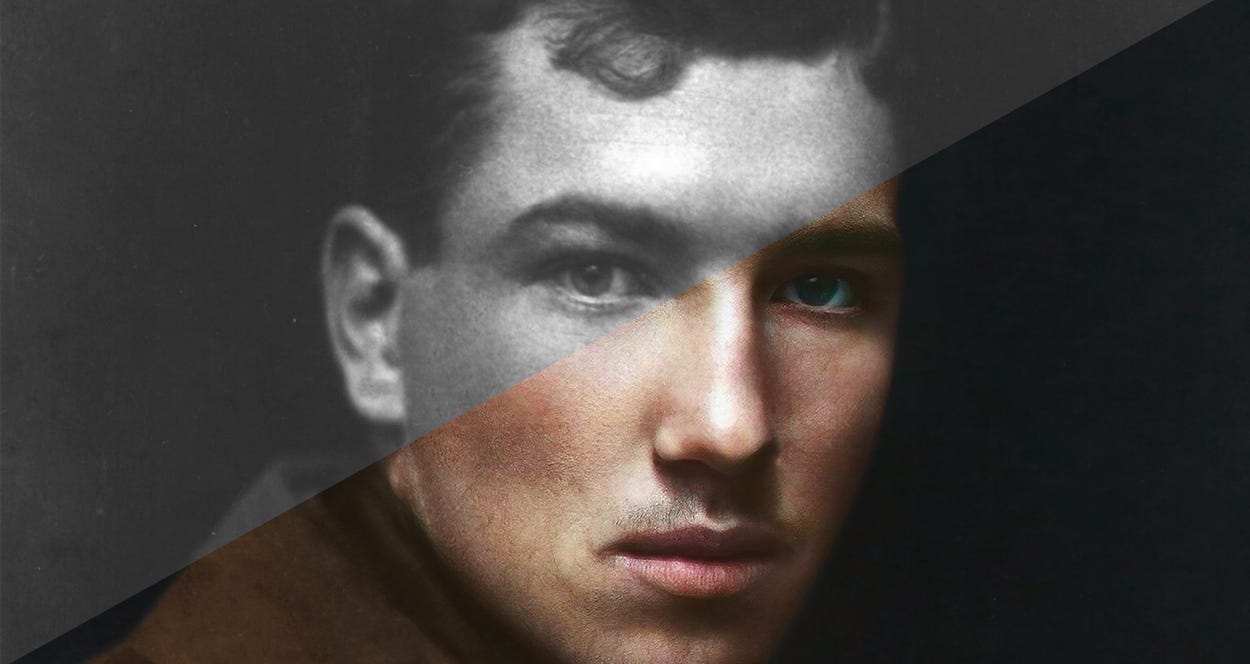

Today, we will be looking at the life and works of Robert Graves.

Please let me know in the comments if you've enjoyed the series and if you would like to see more of these in the future.

Early years

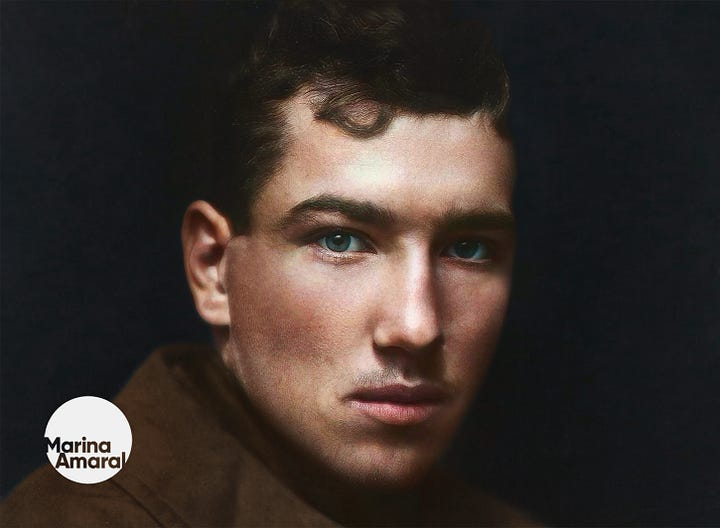

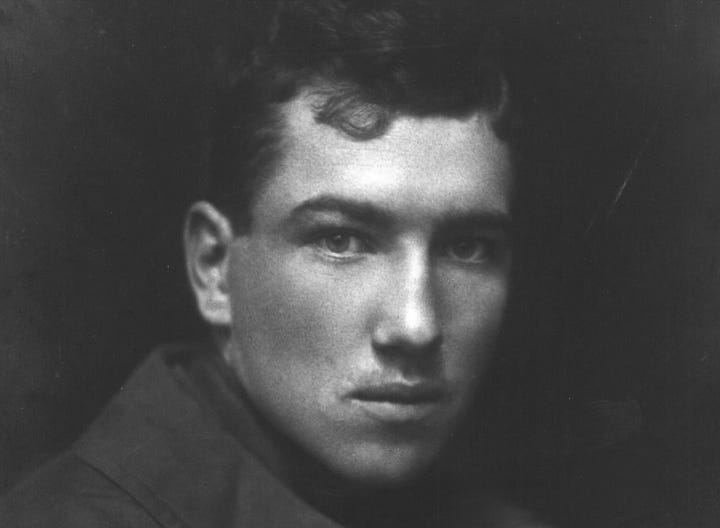

Robert von Ranke Graves was born on 24 July 1895 in Wimbledon, Surrey, the eighth of ten children to Alfred Perceval Graves, an Irish school inspector with a knack for songwriting, notably the popular “Father O’Flynn”, and Amalie Elisabeth Sophie von Ranke, whose German heritage would later pose challenges for Robert during the wartime years (a particularly troubling incident in 1916 saw an officer spread a baseless rumor, suggesting Robert was kin to a captured German soldier named Karl Graves).

As a young student at Charterhouse in Godalming, Surrey, Grave's poetic inclinations began to surface, and his verses earned a spot in the school magazine, The Carthusian. In 1913, he received a scholarship to St. John's College at Oxford University; however, the outbreak of World War I drastically changed his path.

Into The Trenches

On August 1914, a 19-year-old Graves enlisted in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, diving headfirst into the chaos of the Great War.

The following year, amidst the mud of the 1st Battalion trenches, destiny brought him together with Siegfried Sassoon. Both were young soldiers who had remarkable skills with both a pen and a rifle. Their intertwined experiences, which juxtaposed the horrors of battle with their love for poetry, created a strong bond between them.

The depth of their friendship is beautifully depicted in “Two Fusiliers", in which Graves wrote: “Show me the two so closely bound / As we, by the wet bond of blood, / By friendship blossoming from mud...”.

This sentiment was reciprocated by Sassoon in his poem “A Letter Home”, written for Graves:

“You and I have walked together

In the starving winter weather.

We've been glad because we knew

Time's too short and friends are few.”

The latter responded with his own piece, “Letter to S.S. from Mametz Wood”:

“I never dreamed we'd meet that day

In our old haunts down Fricourt way,

Plotting such marvellous journeys there

For jolly old "Après-la-guerre."

However, relationships, much like historical narratives, can be quite complex. By 1929, when Graves published his autobiography, Good-bye to All That, there were certain words written on the pages that deeply unsettled Sassoon and cast a shadow over their once unwavering friendship.

To you who'd read my songs of War

And only hear of blood and fame,

I'll say (you've heard it said before)

'War's Hell! '

Graves's literary journey started to take off during the early years of war. In 1916, he released his first collection of poems called "Over the Brazier." These writings presented a raw and unfiltered perspective on the frontline conflicts, establishing him as one of the pioneering war poets. But not everyone appreciated his writing style. Sassoon himself found some of the poems to be "violent and repulsive", even noting in his diary on 2 December: “Robert Graves lent me his manuscript poems to read: some very bad, violent and repulsive. A few full of promise and real beauty. He oughtn’t to publish yet”

Dancing With Death

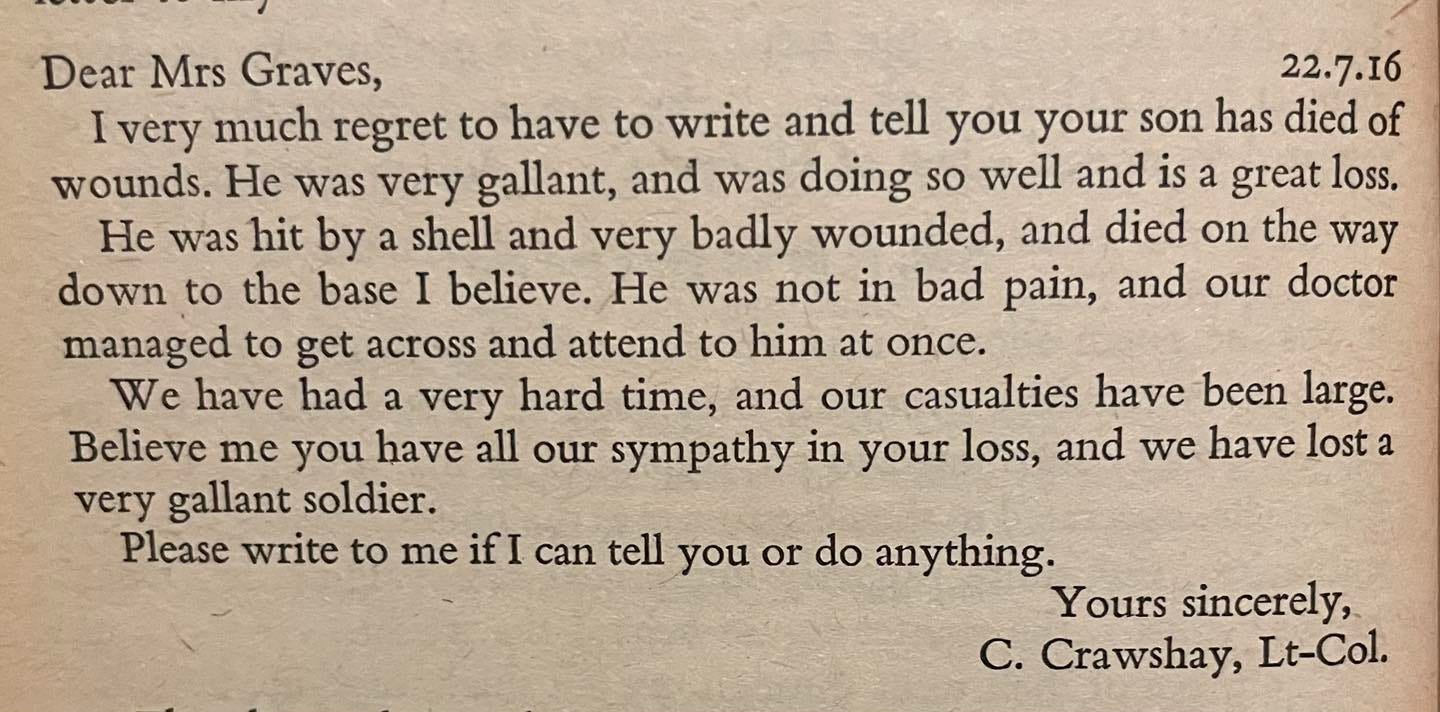

The events of 1916 also witnessed a terrifying and extremely traumatic period in Grave's life. Days before his twenty-first birthday, on July 20, 1916, his battalion was stationed in the Somme region of France, close to the Bazentin-le-Petit Cemetery, when a German shell exploded close to the young poet, penetrating his chest with shrapnel. Rushed to a dressing station near Mametz Wood, Graves’ wounds were so grave that medics believed he wouldn't make it. Mistakenly, they declared him dead, prompting his commanding officer to pen a condolence letter to Graves' devastated parents. The tragic news was further reinforced when The Times listed him among the war dead, on 4 August 1916.

Sassoon, believing he had lost a dear friend, wrote a heart-wrenching entry in his diary:

“And now I’ve heard that Robert died of wounds yesterday, in an attack on High Wood. And I’ve got to go on as if there were nothing wrong. So he and Tommy are together, and perhaps I’ll join them soon. “Oh my songs never sung, And my plays to darkness blown!” – his own poor words written last summer, and now so cruelly true. And only two days ago I was copying his last poem into my notebook, a poem full of his best qualities of sweetness and sincerity, full of heart-breaking gaiety and hope. So all our travels to “the great, greasy Caucasus” are quelled. And someone called Peter will be as sad as I am. Robert might have been a great poet; he could never have become a dull one. In him I thought I had found a lifelong friend to work with. So I go my way alone again.”

Two weeks on, word reached Sassoon that Graves had, against all odds, pulled through. The shock gave way to overwhelming relief, and Sassoon couldn't help but chuckle at the thought of Graves, ever the unconventional one, even in matters of life and death: “Silly old devil […] he always manages to do things differently from other people”.

Graves addressed the mix-up in a letter to Sassoon. He joked about the universe's peculiar sense of timing, having him "die" on his 21st birthday. It was shortly after this horrifying experience, while recuperating in England, that he was informed of Sassoon's audacious declaration “Finished with the War."

Fearing that Sassoon would face a court marcial, Graves intervened on his behalf, convincing a medical board that his friend's defiant stance was a result of shell shock. This strategic move spared Sassoon, who was sent to Craiglockhart instead, where he would eventually meet Wilfred Owen.

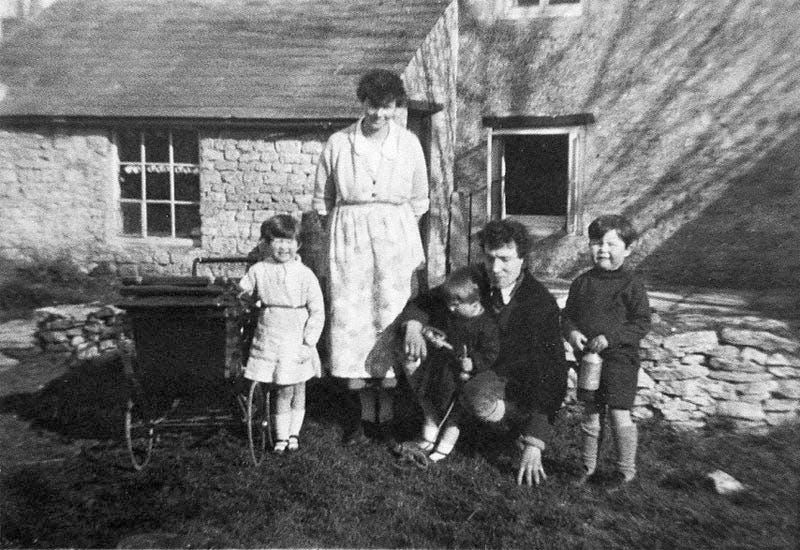

In 1917, the relentless nature of trench warfare began to take its toll, and Graves too fell victim to shell shock. He married Nancy Nicholson in January 1918 and was demobilized a year later, deeply troubled and traumatized by the things he had seen and experienced first-hand. These memories would continue to haunt him for years to come.

“I thought of going back to France, but realized the absurdity of the notion. Since 1916, the fear of gas obsessed me: any unusual smell, even a sudden strong scent of flowers in a garden, was enough to send me trembling. And I couldn't face the sound of heavy shelling now; the noise of a car back-firing would send me flat on my face, or running for cover.”

Beyond the Battlefield

After the war, Graves faced the challenges of reintegrating into civilian life. With a growing family to support, he tried his hand at running a grocery store in Boars Hill. However, when that venture didn't work out, he turned to his true passion; writing.

In an interesting incident from 1924, Graves approached the renowned Virginia Woolf with hopes of collaborating with Hogarth Press. Woolf later wrote about their meeting in her diary, sharing her initial impressions: “The poor boy is all protestation and pose. He has a crude likeness to Shelley, save that his nose is a switchback and his lines blurred. But the consciousness of genius is bad for people. He stayed till 7.15 (we were going to “Caesar and Cleopatra” …) and had at last to say so, for he was so thick in the delight of explaining his way of life to us that no bee stuck faster than honey."

In 1926, Gravess life took yet another turn as he embraced the role of an English Literature professor at Cairo University. Accompanying him were his wife Nancy and Laura Riding, a poet with whom he shared more than just literary interests. This affair added an additional layer of complexity and drama to his already chaotic personal life. He continued to face personal struggles throughout the next few years, as well as a chaotic marriage that ultimately ended in a dramatic divorce. Eventually, Graves and Riding decided to move together to the picturesque village of Deià in Majorca. But even in this paradise like setting, they encountered their own share of challenges. After 13 years together, Riding left him for another writer named Schuyler Jackson.

In the beautiful surroundings of Majorca, Graves found inspiration and produced numerous poems, critiques and notably his highly acclaimed historical novels, I, Claudius, and its sequel. By the 1950s, these works had propelled him to literary stardom and he was recognized with the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry in 1968.

The last chapter of Robert Graves’ life was quieter, marked by health challenges and introspection. He passed away in 1985, aged 90, leaving behind a legacy of over 140 published works.

The journey continues!

As I've explored the lives and works of these war poets, one thing has become clear: art, especially poetry, has an uncanny ability to capture the essence of human experience in ways that most other things can't. These men have reminded me that even in the darkest times, there's a spark of creativity, a need to express, and a desire to be understood. But let's not forget, Sassoon, Owen and Graves are just three voices among a chorus of many. Countless poets, both known and unsung, have poured their souls onto paper, giving voice to the collective trauma, hope, and resilience of their generation. It's been a pleasure diving into their stories and trying to capture the essence of their experiences for you all.

So, as I said in the beginning, I'm packing my bags to retrace their steps with Leger Holidays. It's one thing to write about history, but to stand where history was made? That's a whole different thing.

If you've been inspired by this journey as much as I have, stick around. There's so much more to explore, and I can't wait to share it all with you. And if you haven't subscribed yet, now's the perfect time. Trust me, you won't want to miss what's coming next!

To learn more about the War Poets Tour and many others, visit the website of Leger Holidays.

*I, Claudius* and *Claudius, the God* are certainly major works of historical fiction. Thank you for sharing information about the author's personal life, poetic talents, and war experiences.

"The White Goddess" is full of interesting and thought-provoking facts, although I'm not sire I can accept the book's overall thesis.

His translation of Apuleius' "The Golden Ass" has also held up well.