How Art Thrives in Times of Change, and a Personal Message

where I've been, plus learning that having an identity crisis is actually part of the creative process

Hello, and Happy New Year, everyone!

We’ve made it to another January, and somehow I’m still here oversharing on the internet. After doing this for almost a decade, I think it's okay to call it a tradition at this point. Hope you all wrapped up 2024 nicely and are doing well.

It’s my first post of the year and the first one I’ve published in a while. I wasn’t sure I wanted to write this, mainly because the internet is already drowning in endless rants about artificial intelligence and creativity. Does anyone really need another one? Probably not. But for better or worse, this is what you're getting from me today. BORING, meh, I know. But please, bear with me. I aim to do this with a little self-deprecating humor, and possibly some interesting historical references too.

“All changes, even the most longed for, have their melancholy; for what we leave behind us is a part of ourselves” ― Anatole France, The Crime of Sylvestre Bonnard

Not long ago, AI felt like one of those distant, almost futuristic ideas you’d hear about once or twice while watching a sci-fi movie. Now, though, it’s everywhere, with machines casually vomiting out images, music, and films that can easily be mistaken for human-made work if you're not paying close attention. For people like me, who chose art as a career path (already a very questionable life choice, btw) and tend to overthink everything to the point of exhaustion, watching this happen has been... a lot to process.

Over the past year, I've been haunted by questions about the meaning of creativity today, about what this new scenario means for us artists, and whether there’s still any point in trying to create something from scratch. Do people still care? I tried brushing these thoughts off at first, but that backfired massively and really messed with my mental health. Obviously, working in this field was never meant to be easy (the starving artist cliché exists for a reason), but it wasn’t supposed to feel like a philosophical crisis waiting to happen every time I sit down at my desk either. After a few rounds of all that questioning, the connection I’ve always felt to my work, and my ridiculous belief that feelings and emotions are essential to art, started to feel strangely fragile.

Admitting to that is uncomfortable. Cringe-worthy, even. I’d much rather just bury this conversation under memes, dog pics and lame historical jokes that only you and I would understand, but it’s not like we haven’t had weirder conversations before (remember when we spent an entire evening on Twitter talking about that dude who allegedly preserved Rasputin's penis in a jar? Good days. FYI, the penis is still floating in a jar in the Museum of Erotica in Saint Petersburg, Russia.)

Look at me, still deflecting with bizarre historical facts.

Anyway. The reason I've been so bothered is that I've been watching everything I do get butchered, oversimplified, and basically turned into instant noodles.

“It's not what you look at that matters, it's what you see.” ― Henry David Thoreau

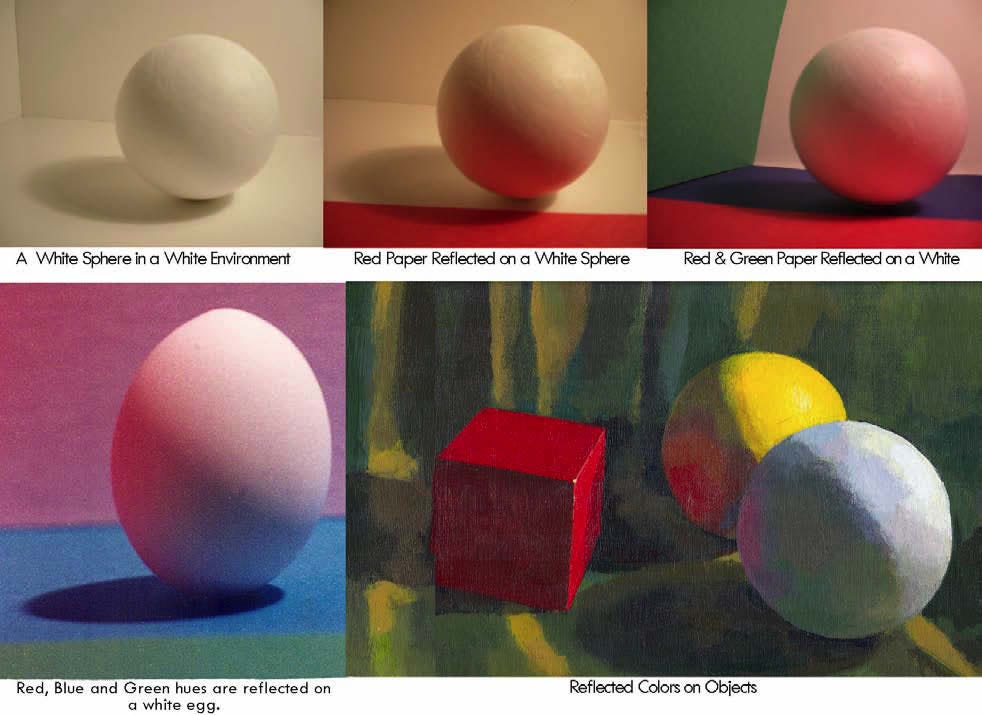

People often assume photo colorization is like painting a children's book: choose some pretty colors, stay within the lines and you're done, but the real work actually starts long before I even touch Photoshop. I know, if you've been here for a while, you're probably rolling your eyes right now, sensing what's to come. I can almost hear the collective sigh, like, "yes, we know, we know, the research is crucial, you've mentioned it about a thousand times." And you're right, I have - because it's true. Every project begins with understanding what I'm looking at.

Okay, it's a black and white photograph. But when was it taken? What street is that in the background, and how has it evolved over time? Can I track down old photos to see how those buildings looked back then? What colors were the shop signs? Was it summer, judging by the shadows and clothing, or a chilly autumn afternoon? Were those buildings made of local stone or imported materials? How would decades of weather and pollution have changed their original color? Were these clothes likely to be well-maintained and vibrant, or worn and faded from daily use? Were they dirty? Is there any way to determine the subject’s eye color? Could the jewelry or accessories in the photo be traced back to specific colors, using contemporary descriptions or archival records?

When working with military photographs, questions like these are very important for me to be able to track down, let's say, the exact shade of blue the French military used in 1915 (bright blue was not a solid choice for trench warfare). Then, I have to figure out how those dyes behaved under different lighting, because that same blue looks entirely different under direct sun compared to a stormy sky.

I could save time by slapping on any random brass color for their buttons (hard to imagine anyone storming in demanding justice for button accuracy), but that’s not how I work. Those tiny details matter because they reflect someone’s lived experience.

That’s the kind of nuance AI doesn’t get and perhaps never will. However, try to explain that to someone who just used an app to colorize their family photos and saw their grandparents in color for the first time. The fact that everyone looks like they just ran of a hepatitis ward doesn't seem to matter. It's a fast option, it's free, and, fair point, it works well enough to impress the cousins at a family reunion. I get the appeal.

Most people enjoy art and creativity the same way they consume any other content: it's just another thing passing by as they scroll through their feed. And to be honest, they're not wrong. When the planet is literally on fire, some new variant of something awful threatens to say hi every other month, and you're somehow trying to manage work, family, and pets while trying to keep your plants alive, who has the mental energy to think about the almost poetic implications and nuances of photo colorization?

"From today, painting is dead!” ― Paul Delaroche (1839, upon seeing the daguerreotype)

This isn't the first time progress has thrown artists into an existential crisis either.

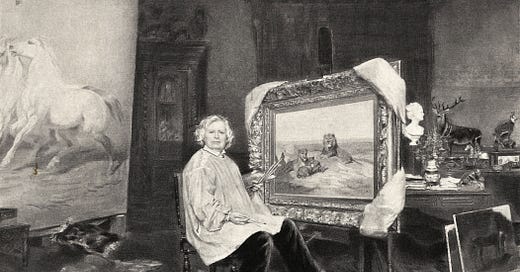

When the daguerreotype, the first practical camera, showed up in 1839, portrait painters were presented with their first real competition. This new device could capture someone's exact likeness in a few minutes, while they'd spent years mastering the techniques of portrait painting. Yet what could have been their undoing resulted in a fascinating change, as photography's arrival inspired and pushed many of them to explore completely new directions. Instead of 'How do I make this look exactly like what I see?' they started wondering 'How does this moment feel? How can I show the way light changes? What does this scene mean to me?'. This shift away from pure representation helped give birth to Impressionism in the 1870s, followed by Post-Impressionism in the 1880s. So, while trying to reinvent themselves and adapt to a new world, these people ended up redefining art itself.

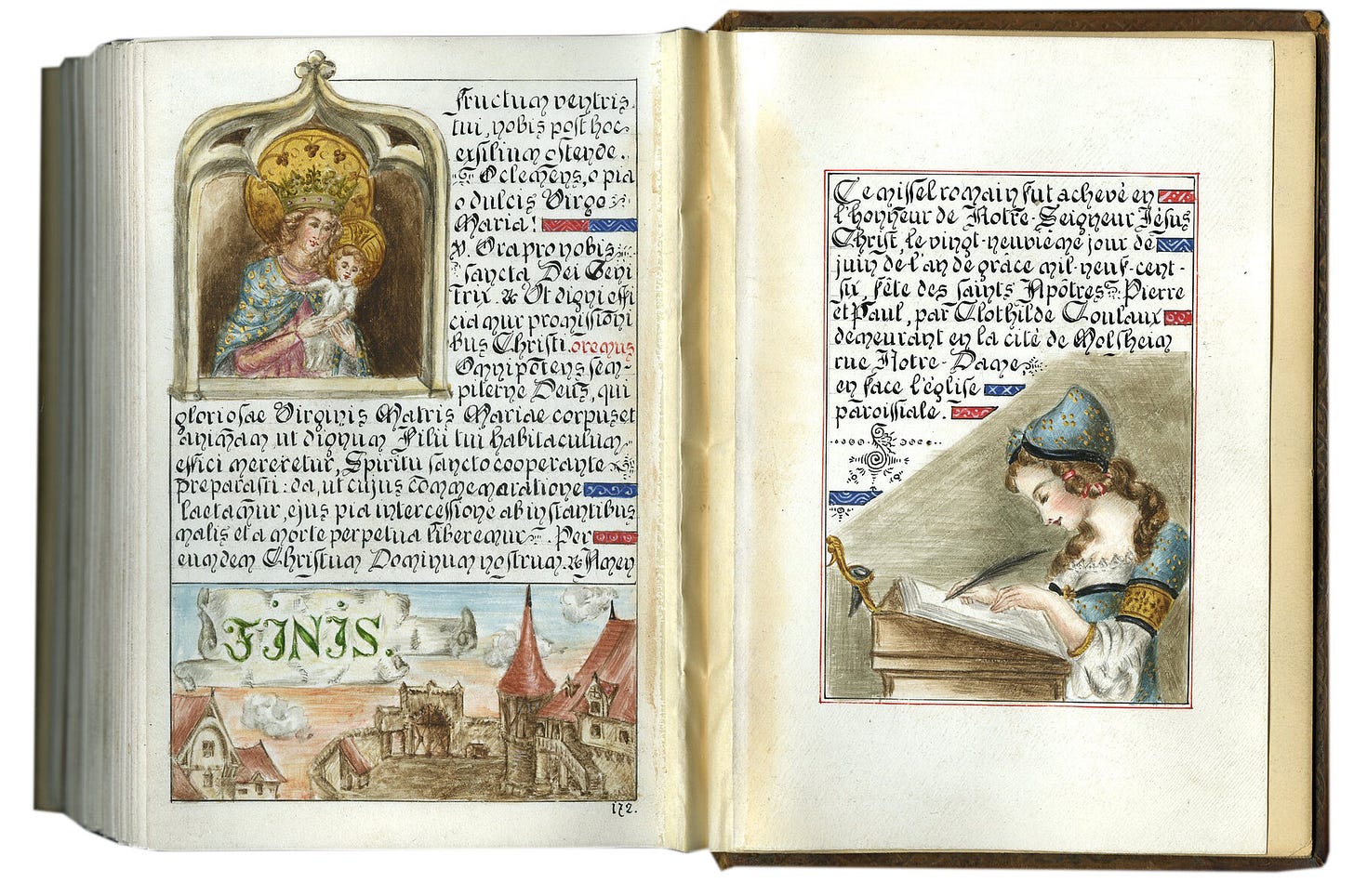

In a similar way, the printing press triggered another massive change. For centuries, books were made by scribes, the skilled individuals who manually copied texts by hand. Some of the most stunningly beautiful books were created this way.

The problem was that each book usually took a very long time to make, which made them incredibly expensive.

This began to change around 1440s, when a German metalworker named Johannes Gutenberg popped up and revolutionized printing with his system of movable type.

Instead of carving entire pages out of wood or copying them by hand, Gutenberg created individual metal letters that could be arranged to form a page of text. These letters were then held in a frame, inked, and pressed onto paper using a screw press similar to those used for wine or olive oil. After printing, they could be rearranged and reused to create new pages, making the process far faster, cheaper and much more efficient than anything that had come before.

To grasp the impact of this invention, consider this: before the Guttenberg Press, there were roughly around 30,000 books in all of Europe. Less than fifty years later, that number grew to an estimated twelve freaking million.

The innovation was undeniably incredible, but once again it came at a human cost, as skilled scribes gradually found their work becoming obsolete. Over the following decades, some adapted by learning to work with printing presses or by making luxury handwritten books for wealthy clients. Others simply couldn't compete, and many traditional workshops closed their doors for good.

Do you notice a pattern here? Every time there's some huge tech breakthroughs, there's this whole creative earthquake that follows, and people, no matter where or how long ago, probably start asking themselves the same questions that I'm asking myself today. Is this the end of my career? Will I end up living in a cardboard box? I'd bet money on the possibility that at some point in history there was at least one artist going through this process who wrote a tearful letter to his mom about how he would have to sell his beloved easel and take up sheep farming.

But somehow, just like always, the dust settles, people adapt, and art finds these weird and wonderful new directions to thrive.

That painter probably never became a shepherd after all.

"Color is my day-long obsession, joy and torment." ― Claude Monet

I know my personal meltdown might seem trivial and even a bit self-indulgent when you consider that AI is out there doing things that genuinely matter, like spotting cancers early or something like that. Sometimes I do catch myself thinking, "Really? You're having an existential crisis over wanting people to understand why getting the perfect shade of khaki matters so much in your colorization?"

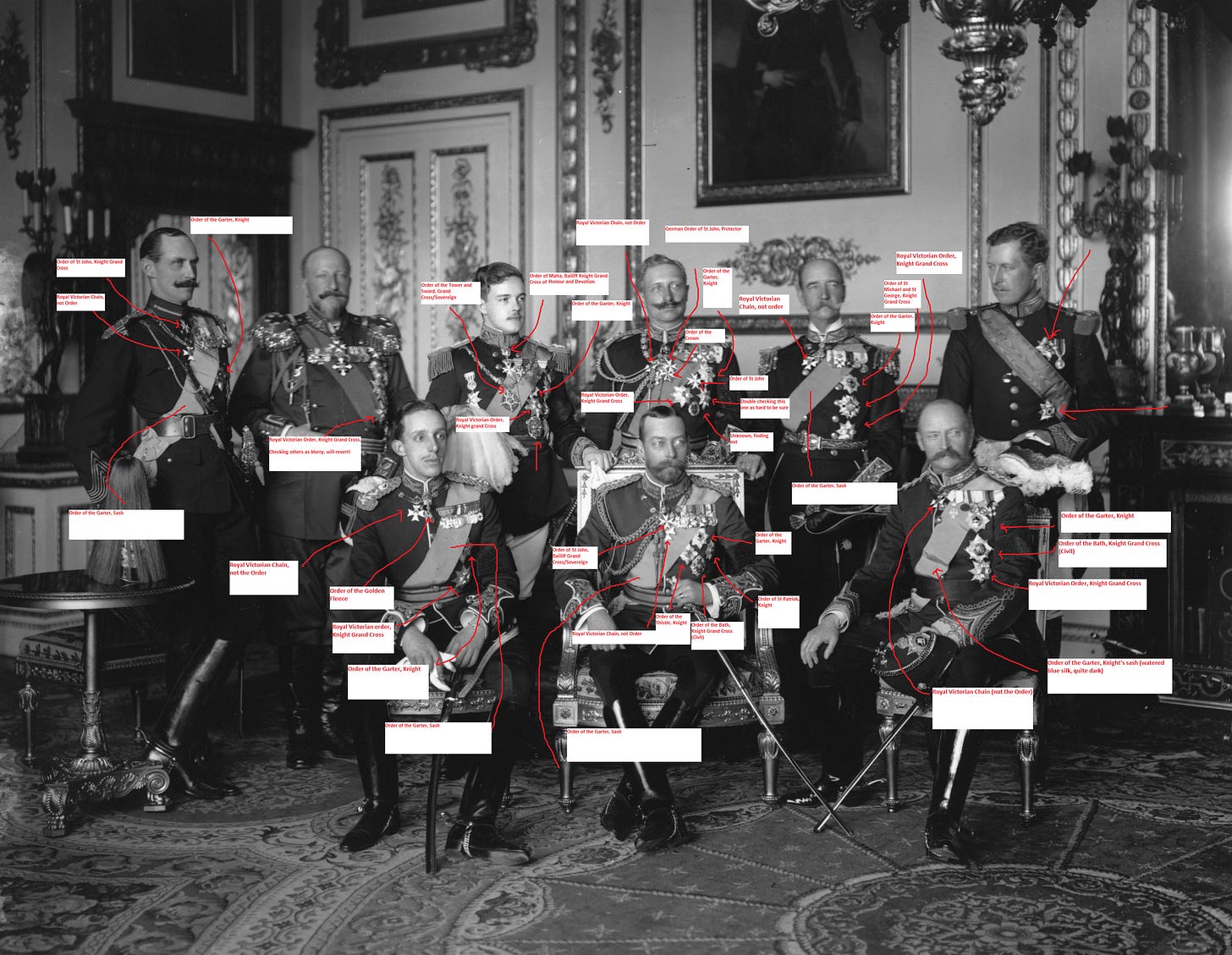

But then I remember what drew me to this work in the first place. It's that feeling of being completely lost in a project, surrounded by coffee cups and reference books, trying to figure out if that officer's medal ribbon should be crimson-over-blue or burgundy-over-navy. I really, truly love those artists who spend months on a single painting, cursing at their canvas at 2am while their dog snores away in the corner; and the researchers who get ridiculously excited about finding the exact shade of yellow used in some dusty medieval manuscript. Maybe it's not the most efficient way to work. Maybe it's even a bit old-school. However, to me, sometimes the old-fashioned way is still the right way.

Years will pass and I’ll probably still be here, zoomed in at 500%, obsessing over the precise shade of a button. That's my way of preserving history and making art. If that makes me the equivalent of someone who nurtures their own sourdough starter for weeks when there's perfectly good bread at the supermarket, well... I've been called worse things.

I'm still terrified of 2025, but at least I know I'm not facing it alone. I've been fortunate enough to build an entire community who cheer me on even when I spend three weeks hunting down a totally irrelevant 1922 coffee shop sign that exactly three people might remember (and even they don't care). You guys are my kind of people, and I couldn't be more grateful for that.

So, thanks for sticking with me. If you've read this far and think this is exactly the kind of historical devotion you need in your life, you know where to find me - whether you want to support this newsletter by becoming a paid subscriber, or have me bring your family photos to life (complete with historically accurate colors and my signature mix of research enthusiasm and mild psychological breakdown). I promise to care too much about every single detail.

In the end, someone needs to keep asking "But what KIND of khaki was it really?"

And I guess that someone is still going to be me.

(see you again very soon!)

Hi Marina, good to have you back. I have your color restoration of the portrait of General Patton hanging on my home office wall. When I look at it, I know that the ribbons on his blouse are correct. I served in the army (with General Patton’s grandson by the way) and this kind of detail means a lot to me. As a retired therapist, I often think about the kids I worked with. What happened to them? How are they? We all second guess ourselves no matter the work. You have a gift, the product of which many of us cherish. So, get busy. We’re waiting to see what you come up with next.

Wishing you a great 2025! Follow your heart and let the Lord take care of the rest.

Chuckle over the sourdough starter...I know someone who actually thought about that and almost did it!