Daguerreotype, a turning point and the beginning of a new era

“I have captured the light and arrested its flight.”

Louis Daguerre, a French inventor born in 1787 in Cormeilles-en-Parisis, Val-d’Oise, France, is widely acknowledged today as the father of modern photography. Building on the work of Nicéphore Niépce, with whom he established a brief partnership in 1829, he created a new form of visual communication, the first commercially viable photographic process: the daguerreotype.

After Niépce’s death in 1833, Daguerre, who had a background in theater design, architecture, and panoramic painting, continued to experiment until he eventually found a way to improve the technique, reducing the exposure time from several hours (sometimes days) to only 20 or 30 minutes.

The new method sparked a movement, giving rise to studios and portrait galleries, and had a significant impact on science, law, and even politics.

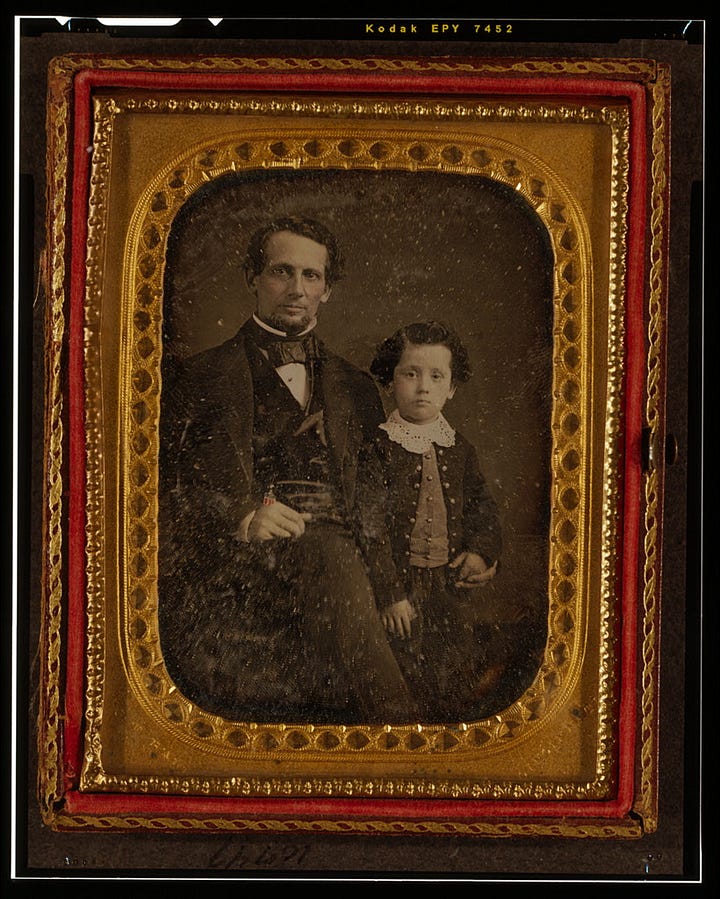

James Presley Ball

In 1849, many years before Gordon Parks focused his camera lens on the lives of Black people, a Black free man by the name of James Presley Ball opened a new daguerreotype studio in Cincinnati, Ohio (the first one was a one-room studio, opened in 1845), known as "Ball's Daguerrean Gallery of the West". In there, Ball, a fierce and outspoken abolitionist who had learned the daguerreotype process a few years earlier in Virginia, from another Black free man, John B. Bailey, held photo exhibitions and oversaw the creation of a 2,500-square-yard panoramic mural put together by a team of local African-American artists, depicting the horrors of slavery (the mural went missing, and what happened to it is still a mystery).

In the years that followed, Ball achieved tremendous success, being commissioned to photograph a number of prominent figures, such as Queen Victoria, Frederick Douglass and Ulysses S. Grant, and became proficient in a range of different photographic methods that came after the daguerreotype, including the ambrotype, the tintype and the stereotype. His work is tremendously significant not only for its artistic merit but also for its historical value.

One of Ball's daguerreotypes sold at auction for $63,800 to a private collector in the early 1990s.

The birth of Astrophotography

In science, the daguerreotype opened important new doors, allowing individuals to study from actual preserved images rather than being restricted to reproductions (paintings, drawings) and living objects.

A great example is John Adams Whipple's daguerreotype of the moon, captured through a massive telescope at the Harvard College Observatory in February 1852.

Louis Daguerre himself captured the first photograph of the moon on January 2, 1839. Unfortunately, a fire destroyed his laboratory and all of his early experimental works two months later.

“I have captured the light and arrested its flight.”

Daguerre had been studying and trying to find ways to capture the images he saw in his camera obscura since the mid-1820s. His experiments with various light-sensitive materials progressed through the 1830s, when he established a working relationship with Niépce.

Utilizing techniques he learned from his business partner associated with original new ones, Daguerre eventually settled on using a polished sheet of silver-plated copper treated with iodine to make it light-sensitive, which was then exposed for several minutes or longer under a lens (he discovered that the image could be developed faster if exposed to mercury vapor). Finally, salt water was used to fix it.

View of the Boulevard du Temple, taken by Daguerre in 1838 in Paris, includes the earliest known photograph of a person. The image shows a busy street, but because the exposure had to continue for four to five minutes the moving traffic is not visible. At the lower right, however, a man apparently having his boots polished, and the bootblack polishing them, were motionless enough for their images to be captured.

A gift free to the world

In 1839, Daguerre revealed and detailed his groundbreaking process to a stunned and captivated audience, members of the Académie des Sciences and the Académie des Beaux-Arts, at the Institut de France.

“The discovery I announce to the public is one of the small number which, by their principles, their results, and the beneficial influence which they exert upon the arts, are counted among the most useful and extraordinary inventions.”

The French Government acquired the patent in exchange for a lifetime pension of 6,000 francs a year for Daguerre and 4,000 francs a year for Isidore, Niépce's son, who had inherited his father's shares of the partnership.

Daguerre was obliged to reveal and publish the instructions for his process, but he shrewdly kept the patent for the equipment required to reproduce the new technique.

The French government finally announced and presented the invention on August 19, 1839, as a "gift free to the world".

Since then, 1839 has been recognized as the official birth year of photography.

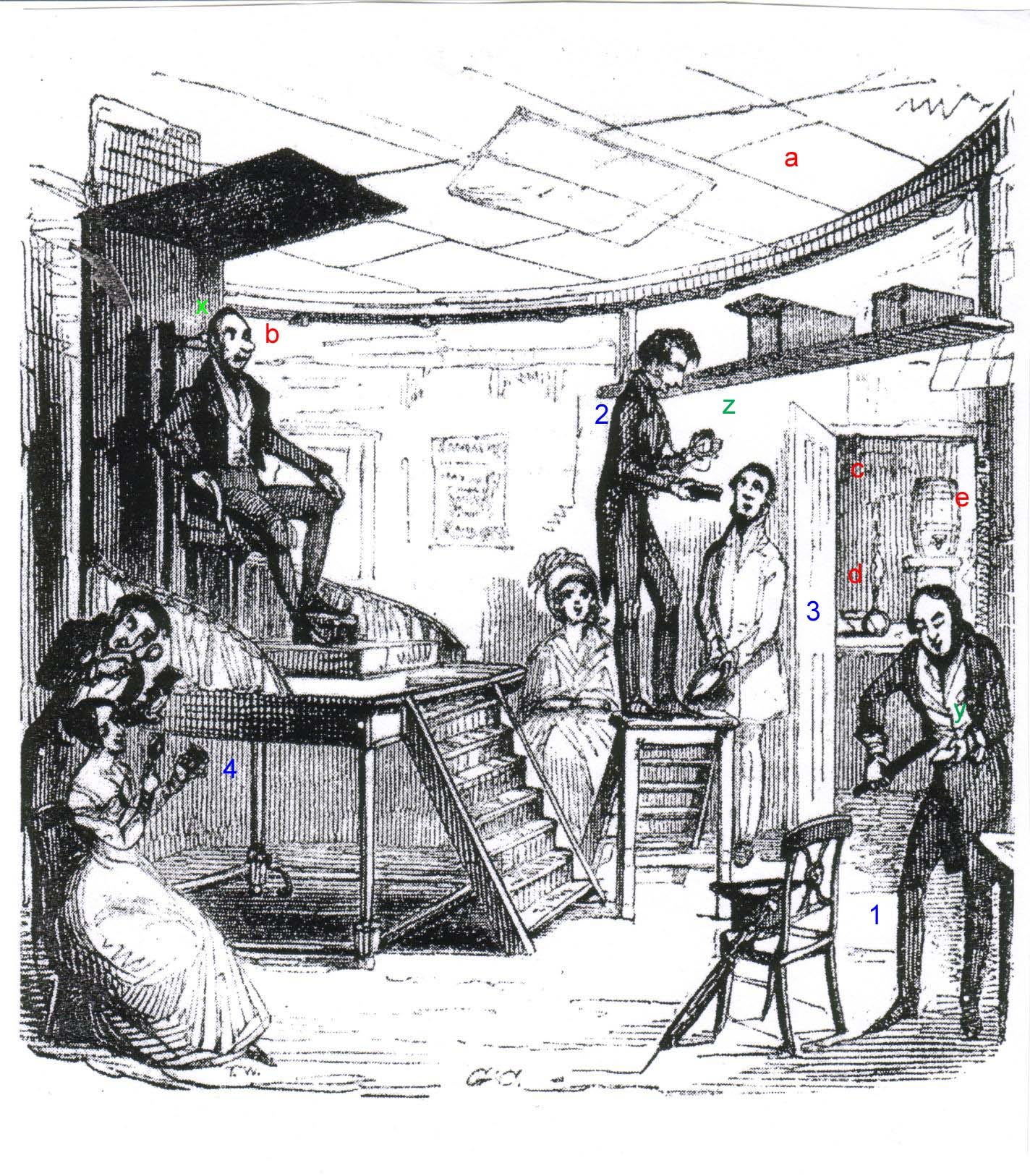

An early daguerreotype portrait studio, 1842

a. A daguerreotype studio was often situated at the very top of a building, which had a glass roof to let in as much light as possible.

b. The subject sat on a posing chair placed on a raised platform, which could be rotated to face the light. The sitter's head is held still by a clamp (x).

The stages of making a daguerreotype portrait

1. An assistant polishes a silver-coated copper plate with a long buffer until the surface is highly reflective (y). c. The highly polished plate is then taken into the darkroom, where it is sensitized with chemicals ( e.g. chloride of iodine, chloride of bromine ).

2. The operator places the sensitized plate into a camera placed on a high shelf (z). When the sitter is ready the operator removes the camera cover and times the required exposure with a watch. [ In this illustration, the operator is using Wolcott's Mirror Camera, which was fitted with a curved mirror instead of a lens ].

3. The exposed plate is returned to the darkroom where the photographic image on the silvered plate is "brought out" with the fumes from heated mercury (d). The photographic image is "fixed" by bathing the plate in hyposulphate of soda. The photographic plate with the daguerreotype image is then washed in distilled water (e) and dried.

4. Finally, the finished daguerreotype portrait is covered by a sheet of protective glass and is either mounted in a decorative frame or presented in a leather-bound case and offered to the customer for close inspection. Early daguerreotype portraits were very small and to appreciate the fine detail these customers are using a magnifying glass.

Daguerreotypomania

Daguerreotyping became a flourishing industry, and people quickly sought to capitalize on the new invention. Dozens of shops opened all across Europe, and the so-called Daguerreotypomania began.

By 1850 there were more than 70 daguerreotype studios in New York City alone. Photographers traveled to villages and towns offering their photography services. By the 1860s, studios had also been set up in Asia and South America.

The craze did not last long, though. The popularity of the daguerreotype began to decline shortly after, in the late 1850s, when a less expensive photographic process became available.

“The sun itself shall draw my pictures.”

Daguerre spent the last years of his life painting dioramas (invented by Daguerre himself and Charles Marie Bouton in 1822) for churches. He died from a heart attack on 10 July 1851 in Bry-Sur-Marne, 12km from Paris.

Today, his name is memorialized, inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Learn More

Subscribe and stay tuned for part 3 of this “history of photography” series!

Love this. Fascinating...

I have next to no knowledge of photography so this was very interesting to read and of course see.