History of photography: Nicéphore Niépce, the pioneer

Although Niépce's process was slow and impractical, his work paved the way for those who came after him

When French inventor Joseph Nicéphore placed a camera obscura aimed toward the view outside the second-story window of his country house in Le Gras, France, in 1826-27, he couldn't imagine the revolution he was about to be a part of.

By then, he had already been experimenting for a while with lithography, a technique invented by Bavarian playwright Alois Senefelder in 1798, which consisted of an artist drawing an image on a smooth, flat limestone surface, taking advantage of the immiscibility between oil and water.

Read More: Litography in the Nineteenth Century

Unsatisfied and recognizing his inability to draw, Niépce began experimenting with different methods and techniques that wouldn't require this skill. He also wanted to find a way to create a permanent image whose lines wouldn't fade over time and couldn't be washed away.

After a series of unsuccessful attempts, Niépce turned his attention to materials that were affected by light, and explored the use of metal plates.

Eventually, an element in particular caught his attention: bitumen of Judea, a naturally occurring asphalt which hardens on exposure to light.

Placing existing engravings, made transparent, onto the surface of pewter plates coated with bitumen, then exposing them to light through a camera obscura - a light-tight box with a small hole in it - he finally achieved his goal. The sunlight “exposed” the plate except for the areas that were covered by the lines on the engraved paper. Finally, the plate was washed in lavender oil and turpentine, removing the unexposed bitumen.

By doing that, Niépce created the process which he called heliography, from helios, meaning "sun", and graphein, "writing".

This famous heliograph was produced in 1826, based on an engraving by Isaac Briot. It pictures a profile of Cardinal d’Amboise.

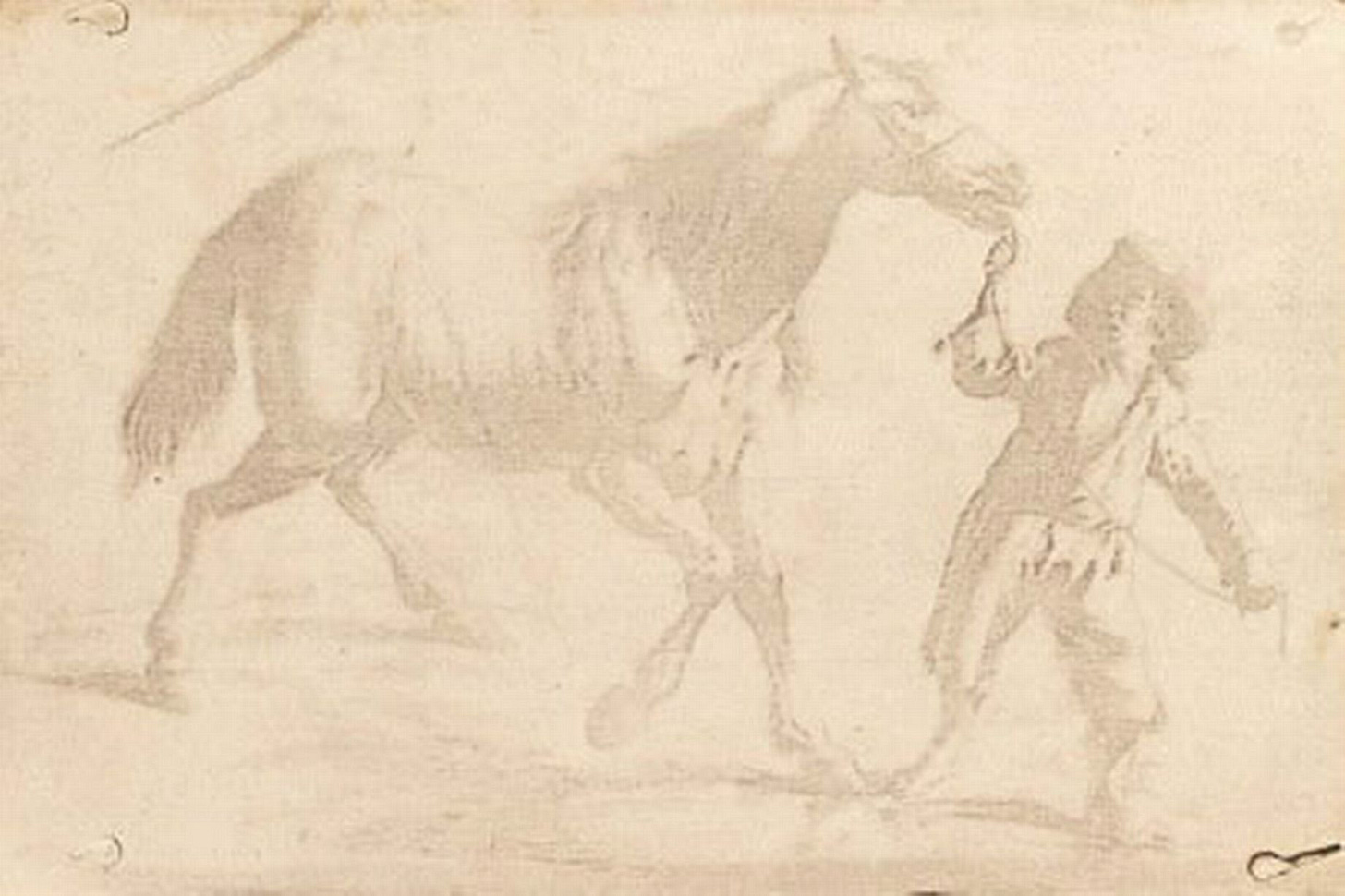

The image below, a reproduction of a 17th century Flemish engraving showing a man leading a horse, was made by Niépce in 1825, and is one of the earliest examples of his process.

The "national treasure", as it was deemed, was bought in 2002 for €450,000 by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

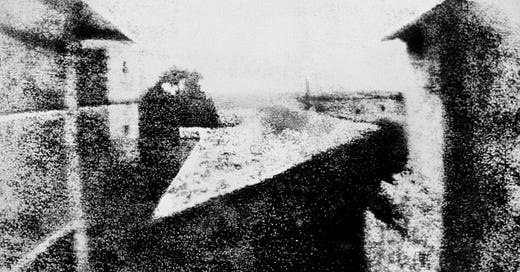

View from the Window at Le Gras

Point de vue du Gras or View from the Window at Le Gras was taken from the window of Niépce's ‘laboratory', and is considered the earliest surviving photographic image.

It depicts, from left to right: ‘the upper loft (or, so-called "pigeon-house") of the family house; a pear tree with a patch of sky showing through an opening in the branches; the slanting roof of the barn, with the long roof & low chimney of the bake house behind it; and, on the right, another wing of the family house.’

It is said that it required about 8 hours of exposure for the image to be completed. The sun moved from east to west during the process - the reason why it appears to shine on both sides of the building.

Some people estimate that the exposure must have continued not for hours, but for several days.

This amazing milestone offered, in Niépce’s words:

“The first uncertain step in a completely new direction.”

The picture fell into oblivion after it was last seen in 1905, until it was rediscovered in 1952 by photo historians Helmut and Alison Gernsheim. They donated it to the University of Texas in 1963 for public display.

View from the Window at Le Gras… today

Harald Johnson writes for PetaPixel:

"In 1999, the French photography school SPEOS became a tenant of the private residence of Niepce’s Le Gras estate when the school’s founder, photographer Pierre-Yves Mahé, rented the part of the house that was used by Niepce as his laboratory-workshop. With Jean-Louis Marignier, a scientist at the French National Center of Scientific Research, they restored and recreated Niepce’s working conditions and rediscovered the site of his photo experiments."

Niépce took the famous “Point de vue du Gras” photo from roughly this position. Pierre-Yves Mahé is shown looking at the floor excavation to determine the window’s original position.

Paving the way

On a visit to the UK in 1826, Niépce showed his work, including View from the Window at Le Gras, to botanical illustrator Francis Bauer, who encouraged him to present his process to the Royal Society. The paper was refused, however, because Niépce was unwilling to share technical details of the process. He ended up handling the paper and the specimens of his work to Bauer before returning to France.

In 1829, after failing at his attempts to shorten the extremely long exposure times that were required to develop the images, Niépce agreed to a partnership with Parisian painter Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre to improve and market heliography. He died of a stroke a few years later, in 1833; his contributions chiefly unrecognized.

This allowed Daguerre to later hail his own process as the first developed method of producing photographic images.

Why is the invention of photography typically credited to Louis Daguerre?

As historian of science William B. Ashworth, writes:

"It is a convoluted, and sad, story. Niépce travelled to England in 1827 to tend to his mentally ill brother, and he brought several heliographs with him. He met people who were quite interested in his process, and he tried to make arrangements to give a demonstration to the Royal Society of London. However, everything went wrong, and it really was no one's fault. The Royal Society was practically dysfunctional at the time, as the president, Humphry Davy, was dying, and there was considerable scrambling to determine his successor. John Herschel, who would be a photographic pioneer himself in the 1830s, was so disgusted with the Society that he resigned his position as secretary and refused to attend meetings. The upshot was that the presentation never came to pass, and the people who would have been the most interested in Niépce’s demonstration, like Herschel, never met Niépce or saw his work. Niépce returned home, his heliotypes still in his luggage, and although he lived until 1833, and collaborated at the end with Louis Daguerre, he gradually disappeared from public view. When the Daguerrotype (a different type of photographic process) was first demonstrated to a revitalized Royal Society in 1839, Niépce's name was all but forgotten. Niépce did all the right things, but he never reached the right people. Had he made his trip to England a year earlier, or even a year later, he might have found a receptive audience, and the history of photography might have played out quite differently. Life is like that, sometimes."

Despite his significant achievements, Niépce's process was slow, impractical and had several limitations. Nonetheless, his work laid the foundation for the development of photography, and paved the way for those who came after him.

Further reading

Next: Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre and the invention of the daguerreotype. Subscribe and stay tuned!

I love reading this story once and again. Here with some new enlightenment. Just a tip, Daguerre was the one becoming famous and giving name to the first process, although Niepce was equally recognized (and paid) by the French Government. And, one more to your list: Capturing the Light by Roger Watson & Helen Rappaport

Thank you very interesting.