What should and what shouldn't be colorized?

What is the limit and who defines it?

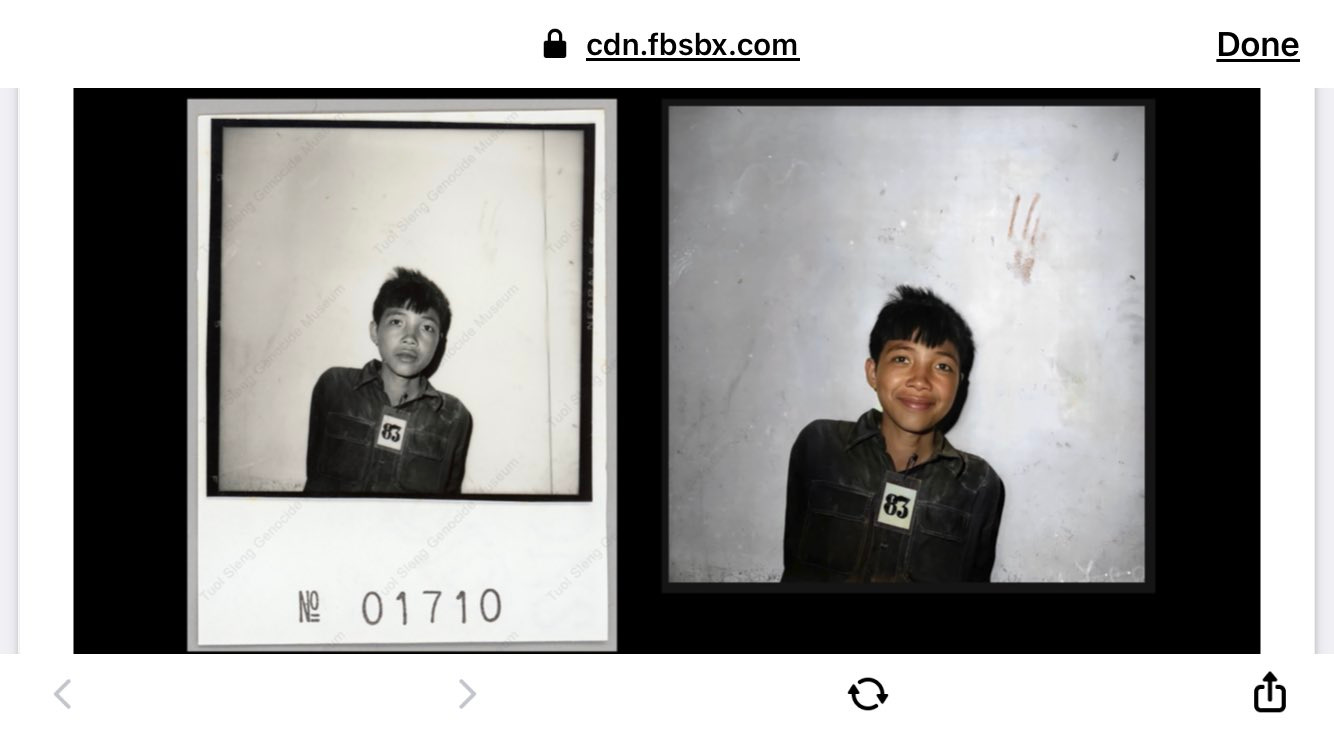

Last year, an important debate about the limits of digital manipulation and photo colorization was sparked by a now-deleted article published on VICE titled 'These People Were Arrested by the Khmer Rouge and Never Seen Again'. The article featured photographs of victims of the Cambodian genocide (1975-1979), in which approximately 1.7 million people lost their lives. What made everyone so enraged (myself included) wasn't the fact that these photographs had been restored and colorized by a digital artist, but the fact that smiles were added to the victim's faces, using artificial intelligence, in an attempt to, according to the artist, “humanize them”.

The colorization wasn't the problem here, but I think this illustrates very well the point that I'd like to discuss today. What is the limit?

This episode made me think a lot about my responsibilities.

At the time when all that happened, someone writing for a magazine tried to draw comparisons between this project and the project I created and launched in 2018, supported by the Auschwitz Memorial and Museum, called Faces of Auschwitz.

This entry is not an attempt to explain why this comparison was extremely unfair, but to use my platform, created on the basis of doing just that: colorizing historical photographs; to reflect on what I think we should have in mind when altering historical photos. It's a sensitive and maybe complex subject, but one that can not be overlooked.

Making history less abstract

When talking about nasty figures from the past, it's easy to feel that such a person only exists in history books. To me, this is why “humanizing” - in the sense of making that person relatable (which DOESN'T mean that we are transforming them into a “wonderful person with a pure heart”, of course) is important. Because it is only by understanding that a human being was capable of masterminding, commanding and/or executing horrendous acts that we become more capable of identifying where the danger is actually hidden. We are not looking for a green creature with purple eyes and horns; or even for a black and white one. We are looking for someone who can look exactly like a neighbor or a friend. And, on the other hand, when we humanize victims, we empathize more. We can relate. We connect with their suffering on a different level.

So, basically, history becomes less abstract and more tangible. And discussions that maybe wouldn't have happened otherwise lead us to a greater understanding of the whole matter that is being analyzed (maybe this is what the artist behind that project tried to achieve, but did so in a very insensitive, confusing, disrespectful, and weird way.)

In our context here, colors are the tools that we use to evoke those emotions, but there are other ways of doing that.

Of course, some people simply don't even need a colored photograph: they can feel exactly what I described just by looking at the black and white. The original is enough: they can connect, they can empathize, their attention is captured. But others need something else. I've received countless emails over the years from teachers who used my photos in classrooms and noticed a considerable improvement in their students' engagement in history classes, which reinforces my point.

The idea of making something more relatable works, too, with less complex subjects, such as a photograph of a historic football match or one of random people wandering around on the streets. Are you used to watching football matches in black and white or in color? What seems closer to your reality? What feels more familiar to you?

We don't always need to get caught in a rabbit hole and profound debates. This isn't the goal every single time. Sometimes it's simply just fun to realize that history didn't happen in black and white, after all.

The huge challenge from an artist's perspective is finding the right way to do all that without crossing the line. There are limits that we need to respect, but defining exactly what that limit is is a challenge too. It's really, really easy to mess up.

After 7 years of working in this field, I've developed a strategy. Before starting a new project, I ask myself: What will people gain from seeing this photo in color?

Faces of Auschwitz

What I had in mind when I designed what became Faces of Auschwitz and presented the idea to the Auschwitz Museum was the desire to encourage people to learn more about the Holocaust and the genocide perpetrated by Nazi Germany than what they had learned in school. I wanted them to really put themselves there. To feel that those victims could have been a neighbor or even a school friend. I wanted to individualize the stories, to give a name to as many faces as I could. I wanted to make history less abstract. I wrote more about this here.

But I also knew that the risk of doing all that in a way that could offend and disrespect the victims, although I had only genuine and very good intentions in my heart, was huge. So I first presented the idea to a few Holocaust survivors (or their relatives) to hear what their feelings were towards the project. My dear friend Eva Kor, one of the survivors of the experiments with twins performed by Dr. Joseph Mengele in Auschwitz, talks a little bit about it in this video.

We took FoA very seriously from day one and went ahead with the project only after receiving the green light from the Auschwitz Museum. They were essential in this process and helped us understand how far we could go. Every new photo and every new post passed through them first (or was written by someone in their team), and we made changes whenever necessary.

I did nothing more than restore and colorize the photographs (the colorized version was presented beside the black and white on our website.)

Still, we were aware that we could (and probably would) commit mistakes. Getting help from people who are directly involved with the subject that we wanted to discuss was crucial. We understood that we needed to pay attention and consider how they, above everyone else, felt about what we were doing. That was our thermometer. They drew the line and established the limits for us.

I know we did our best. It was far from perfect, but I'm very proud. And I'm also very grateful to everyone who contributed. We couldn't have done what we did without them.

Take a moment to explore our website and read the stories we've published: here.

(Our documentary is in the works!)

Final thoughts

So…

Should we colorize photos that were taken when color photography was already readily available, assuming then that it was the photographer's deliberate choice to take them in black and white? Should we even think about that, considering that the original will always exist and won't be damaged in any way?

Are there any subjects that we should consider untouchable?

How can we ensure that we are not being disrespectful to the photographer, the historical photo as an original document, and to history itself?

I don't have definitive answers, but I'm always reflecting on those questions. That is a good starting point, I think: recognizing that we, as professionals, are not simply having fun and ‘applying colors’ to photographs. We have a very real responsibility, especially when we have a platform.

I hope I can learn from the mistakes I'll commit along the way, as has already happened a few times in the past. And I thank you guys for supporting me and for helping me figure out the answers to all those questions.

I'd love to hear your thoughts. Please leave a comment down below and share them with me.

Love,

Marina x

Everyone has their own limits.

My limit was hit when I saw the picture of the young 13 year old child in Auschwitz (the one in your blog thumbnail) was colorised and animated using AI. The colorisation wasn't the problem it was the animation , it was not approirate to make her smile , the child was clearly suffering in the photo, the whole context of it and fact that we know she was ultimately murdered by the Nazis, this seemed a total disrespect to me. Of course some where not bothered by it.

A beautifully written analysis. I recently found your work and seeing colorized photos has always given me a hesitant feeling though I didn’t really know why.

I’m a photographer, mostly capture Crows in the PNW. I have from time to time toggled the B/W button on an image just to see what a “classic” treatment would do. And I always revert back to color thinking it’s just missing the one thing that connects me to it...

That odd feeling I have when seeing colorized photographs is the same as when that company used AI to animate old photos,..watching 80 year spouses see their long lost loves alive again if only for a brief 5 sec loop (which is simply magic imo..) it somehow makes that which was unaccessible real.

This piece explains the complexity of how I feel so well. Light into corners I didn’t know I had.

I really appreciate your heart in your work bringing the past back and allowing us to see the life that once was.

It’s so relatable it feels existentially wrong for some reason,..like as if we discovered timetravel and I could go back and see my parents watching TV together before I was born. Should I witness that? I don’t know, but I want to.

Thank you for such a thoughtful piece, I’m really glad I found your work. Can’t wait for the doc!!