The man who (literally) stole Einstein's brain

and I'm not even joking

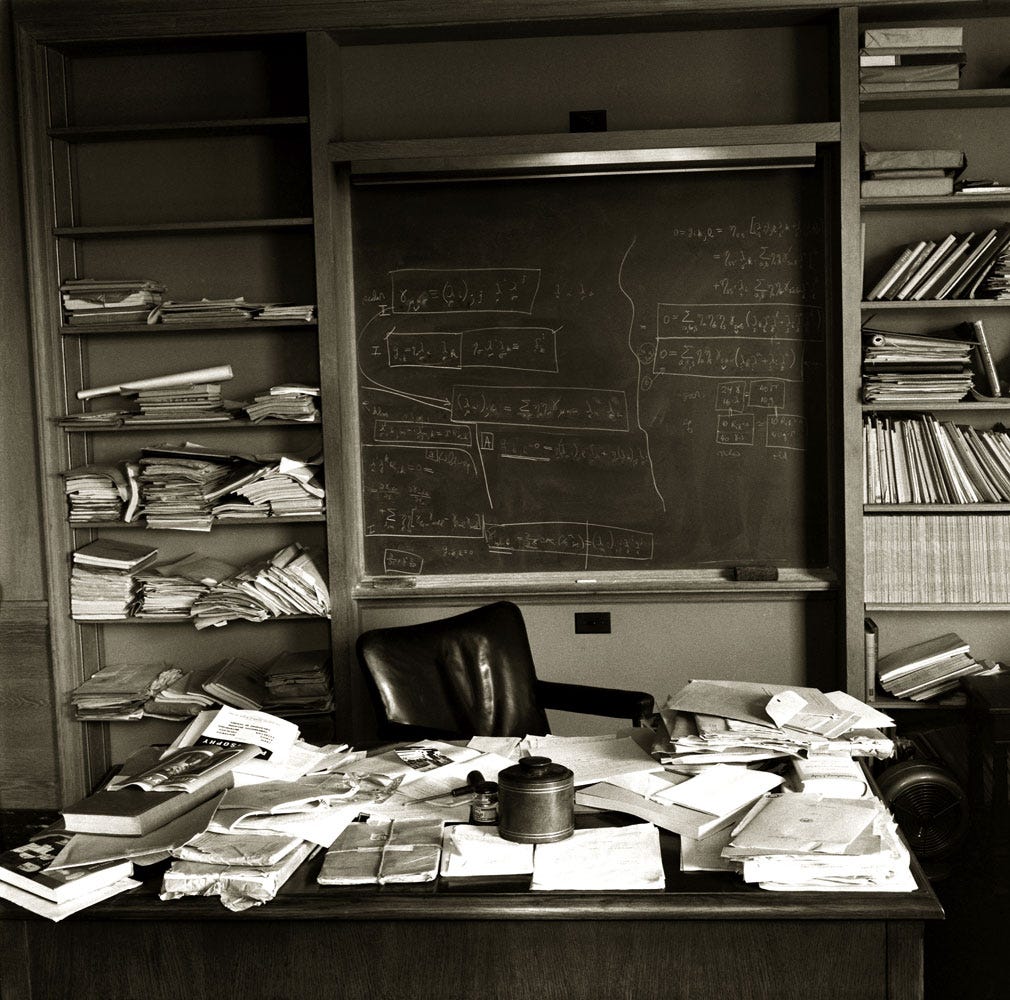

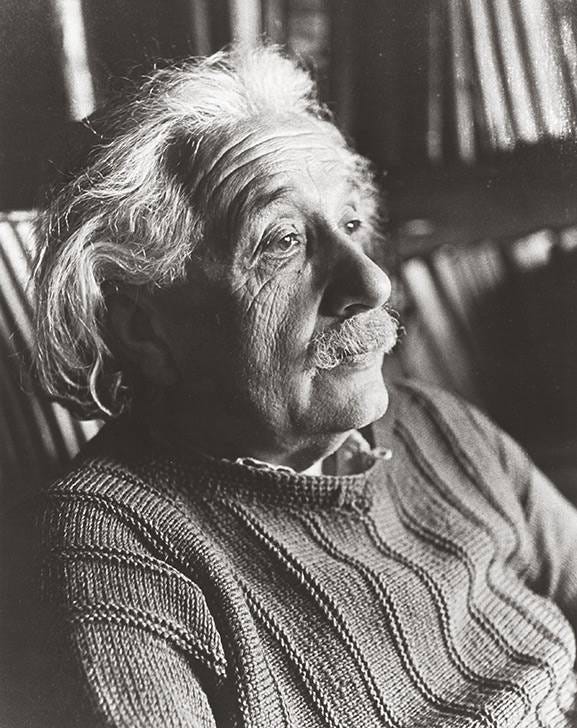

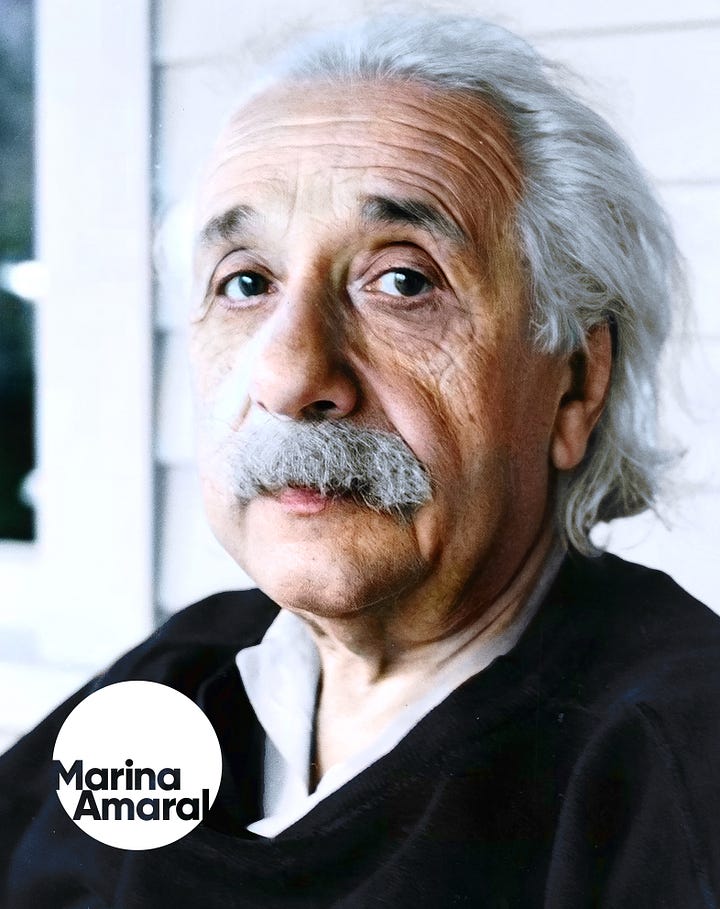

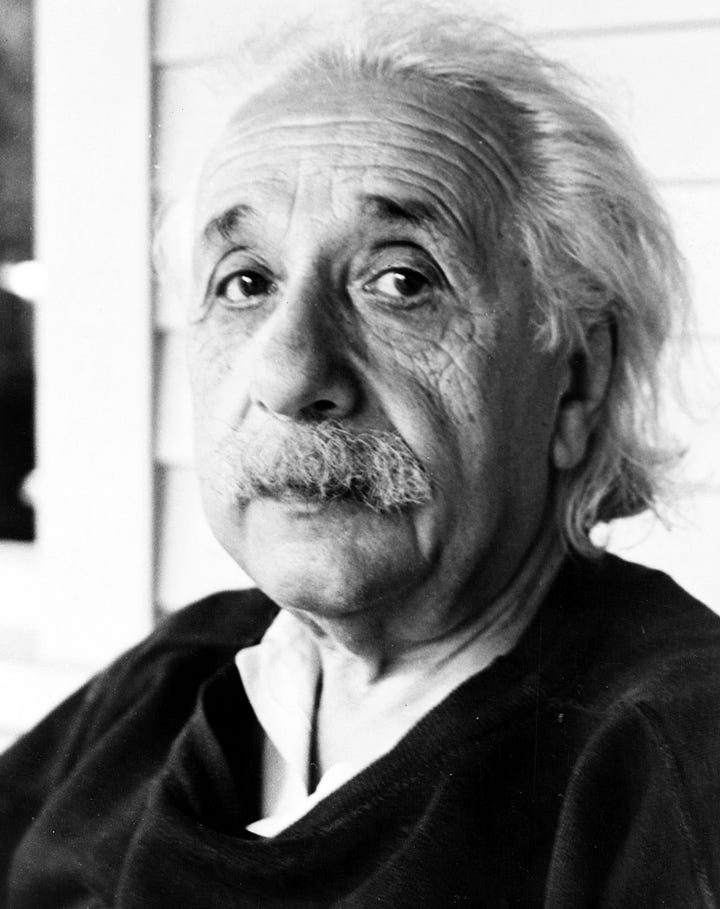

On April 17, 1955, Albert Einstein's Sunday was shaping up to be anything but ordinary. There he was, seated at his messy desk (who am I to judge?) in Princeton, New Jersey, surrounded by a pile of papers and books, when suddenly, a familiar pain in his chest intensified, transforming into a sharp, unbearable agony. This was no stranger to Einstein; he had been living for a while with an aortic aneurysm, a potentially lethal condition where the heart's main artery develops a dangerous bulge. Despite undergoing surgery in 1948, the aneurysm persisted as a constant, silent threat. On that morning, it finally ruptured.

Rushed to the hospital, the 76-year-old scientist opted out of further surgery and declined any other possible treatments. He firmly believed in living on his own terms, even in death. "I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially," he declared. "I have done my share; it is time to go. I will do it elegantly."

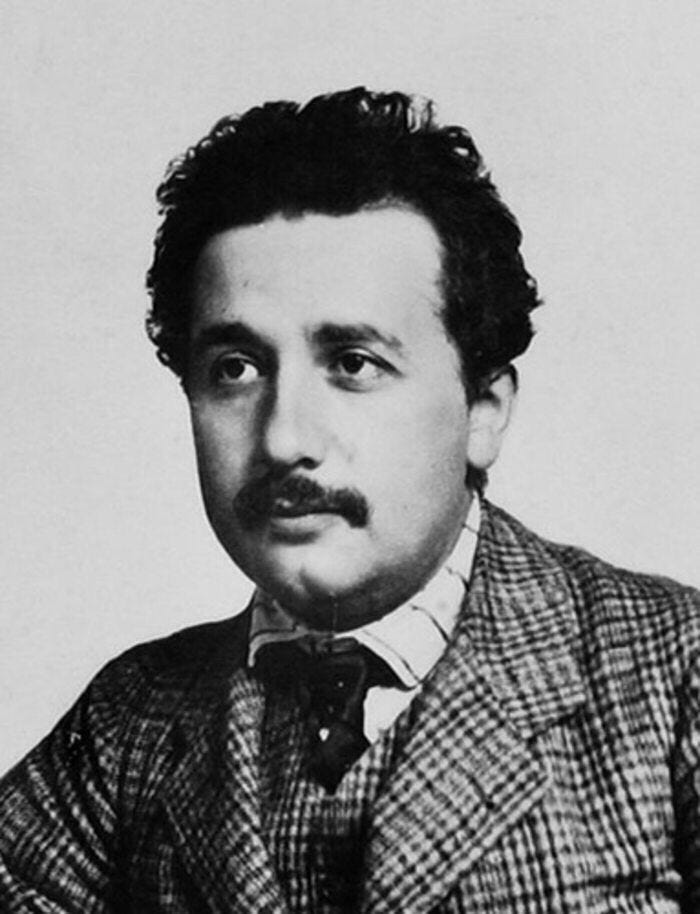

Albert Einstein was born in 1879 in Ulm, in the Kingdom of Württemberg in the German Empire. His dad, Hermann Einstein, was a salesman and later ran an electrochemical factory. His mom, Pauline Koch, was a homemaker and was known for being a quiet and loving person.

While most kids his age were probably more into swapping marbles, running around like little mad energy bombs, or maybe into punching themselves in the face, young Albert was already thinking, "Meh, not for me."

When Einstein was five, his dad gave him what might have seemed like a boring gift to any other kid: a compass. Though nobody knew it at the time, that small object would change the young boy's life forever.

“A wonder of this kind I experienced as a child of four or five years when my father showed me a compass. That this needle behaved in such a determined way did not at all fit in the kind of occurrences that could find a place in the unconscious world of concepts (efficacy produced by direct “touch”). I can still remember — or at least believe I can remember — that this experience made a deep and lasting impression upon me. Something deeply hidden had to be behind things.

In 1895, Einstein made his way to Switzerland, and in 1897, aged seventeen, enrolled in the mathematics and physics teaching diploma program at the Swiss federal polytechnic school in Zürich, where he graduated in 1900. Then, in 1905, he topped off his academic journey with a successful PhD dissertation. After finishing his studies at the University of Zurich, he returned to Germany to take up a professorship at the University of Berlin. His career was on the rise, but everything changed when little sucker Adolf Hitler came to power in the early 1930s. For Einstein, a Jewish man who was no idiot, the signs were clear: Germany was becoming a dangerous place to call home.

“I would rather be torn limb from limb ... than take part in such an ugly business.”

Watching closely as the threats grew and the violence escalated, Einstein began to publicly voice his opposition against the new government, which, of course, didn't make the Nazis happy. They threatened and trashed him in the newspapers, dismissed his groundbreaking work, including his Law of Relativity (because they were the real experts on physics), and burned his books in public bonfires. The situation deteriorated even further, and Einstein cut ties with the Prussian Academy of Sciences, a prestigious institution he had been a proud member of, and renounced his German citizenship. The authorities doubled down, froze his bank accounts, and raided his property in Germany over some ridiculous claims that he was hiding weapons in there.

At that chaotic point in his life, with his life clearly in danger, Einstein was a mess. Fortunately, a lifeline appeared in the form of the Academic Assistance Council, an organization founded by William Beveridge in April 1933 to help academics fleeing Nazi persecution. With their assistance, the renowned physicist managed to escape the threatening atmosphere in Germany, finding temporary refuge in a rented house in De Haan, Belgium. His stay there wouldn't last long. By late July 1933, he was on the move again, this time to England, following an invitation from Commander Oliver Locker-Lampson, a British MP. Einstein was offered a quiet retreat in a wooden cabin located on Roughton Heath in Norfolk. In October 1933, he accepted an offer from the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he lived for the rest of his life.

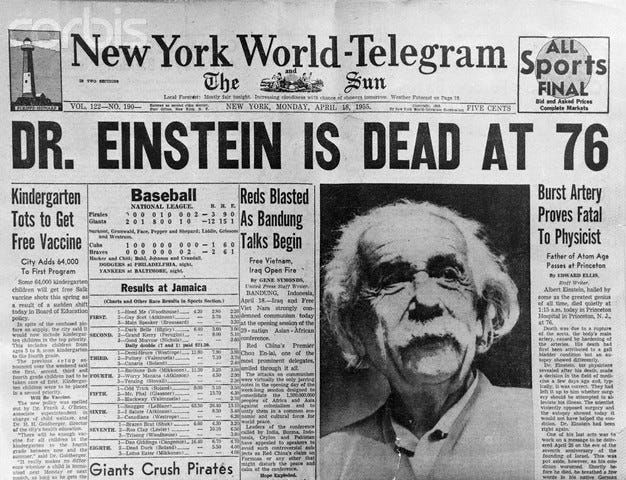

When Einstein died on April 18, 1955, the whole world felt the loss. The New York Times summed it up perfectly in its headline the next day: "Einstein Dies in Sleep at 76; World Mourns Loss of Great Scientist." It was an understandable reaction to the departure of a man who had dared to imagine the universe in ways no one before him had.

Surprisingly, though, Einstein's personal preferences for how he wanted to be remembered were quite humble. In a conversation with his biographer, Abraham Pais, he stated his wishes for his body "to be cremated so people don't come worship at my bones." For him, the idea that people might one day go to his grave, treating his remains as some sort of sacred relic, was utterly ridiculous.

But few people could have predicted that the actions of one individual would completely transform the next coming days. What was meant to be a dignified goodbye turned into a macabre circus that completely disregarded the genius' final wishes, and transformed his death into a horrible shitshow.

"A question that sometimes drives me hazy: am I or are the others crazy?”

Guys, looking back at the history of medicine with all the tech and knowledge we have today is a real trip - fascinating yet very scary. I highly recommend you do it one day. It’s kind of like reading through your old social media posts and part of you is thinking, "wow, I've come a long way," and the other part is like "what the hell was I doing here?"

Historically, medical practices were a wild mix of guesswork and inherited traditions, not exactly the precise science we know now. Sure, people were working with what they had, but let’s just say you wouldn’t want to go back for a doctor’s appointment.

It wasn't until the late 1800s that medicine really began to evolve. Prior to this period, medical standards (or lack thereof), particularly in terms of hygiene, were remarkably reckless; doctors frequently did not wash their hands after treating patients and even reused the same tools without sterilization. Fortunately, as time passed, people's perceptions began to change, and thanks to the work of pioneers like Joseph Lister (yep, the Listerine guy), the importance of germ-free environments became common knowledge. Lister promoted the use of antiseptics after realizing that many infections were caused by microorganisms that could be killed before they entered the body during surgery. Before this, surgeries were not so different from a carpenter sanding down a piece of furniture in a dusty workshop, which is pretty horrifying when you think about it.

Similarly, if you think a visit to the dentist is scary now, imagine what it was like before the routine use of pain management. Ether and chloroform became popular as anesthetics only in the mid-to-late 19th century. Before that, patients often got a strong drink, a stick to bite on, and a reassuring pat on the back before the doctor began his work. Not exactly comforting.

But that's the amazing thing about science: it learns from what doesn't work as much as from what does. And this whole process of trying and failing to eventually succeed, and of being curious and investigating further when you need more answers, it's really what drives scientific progress forward.

Of course, as exciting as this quest for knowledge is, we've got to remember to play by the rules. Just think about what it'd be like if there were absolutely no boundaries or guidelines. You might end up with doctors making decisions without patient consent, or even wilder, researchers could go to extremes like, I don't know, maybe swiping brains just because they wanted to.

Thankfully, we don't gotta stress about those kinds of crazy stories in real life.

Right?

…

Right?

…

Guys, are you still there?

"A question that sometimes drives me hazy: am I or are the others crazy?”

The human brain has been a giant question mark for scientists forever. We've made a lot of progress in the past few decades, but figuring out how all of the different parts of this incredible organ work and how they coordinate so smoothly still is a huge challenge. This thing is absolutely and completely involved in our daily lives, whether it's controlling our emotions, regulating our heartbeat, processing sensory information, obsessing over how many marshmallows we can stuff in our mouths (yeah, don't worry, we've all been there), or simply helping us remember where we put our keys. No wonder even a tiny glitch in this system can cause big problems and sometimes lead to serious, even fatal, consequences.

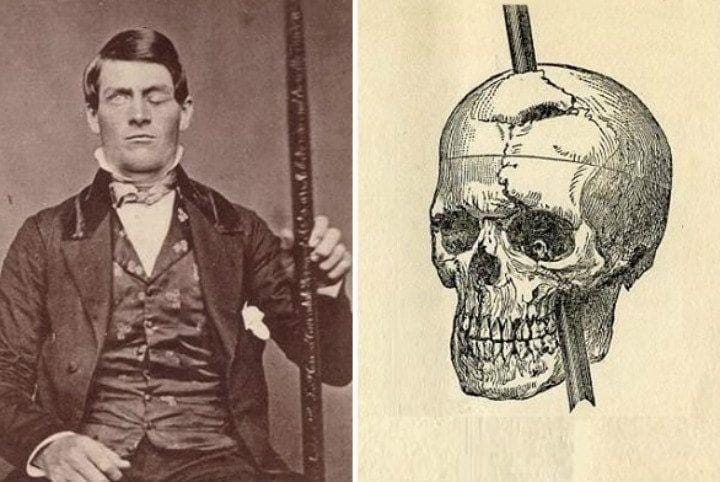

A perfect example of this happened back in the mid-19th century with a railroad worker named Phineas Gage.

In 1848, Gage was busy packing explosives into a hole for new railway tracks near Cavendish, Vermont. It was just another day at the office for him, doing something he'd done more times than he could count on his fingers and toes combined. This time, though, something went horribly wrong. The explosive detonated too early, sending the tamping iron (a massive beast - 43 inches long and 1.25 inches in diameter) shooting like a missile straight through his cheek and out the top of his skull. By all accounts, this should have been a fatal blow, but Gage miraculously survived. More than that: minutes after the gruesome accident, he was not only conscious but also talking and walking. Dr. Edward H. Williams, the first doc to get there, had no clue what he was about to walk into. What he saw was a living, breathing human being with a massive, gaping hole in his... well, you get the picture. How do you even approach that situation without your jaw hitting the floor?

Now, as for Gage, guys, this man greeted the doctor with a line that would make him legendary: "Doctor, here is business enough for you."

Well, my guy, this is A BIG, BIG UNDERSTATEMENT.

Gage's physical recovery was amazing, given how bad his injury was. But the real story here is how, after this episode, his personality completely changed. Gage used to be described as a cool, smart, and efficient guy. Post-accident, though, he became erratic, impatient, impulsive, and even started swearing a lot, which was completely out of character for him. It was one of the first times science witnessed such a dramatic transformation in a person after a brain injury. This case showed us that certain parts of the brain are directly connected to personality and behavior and that when these parts get damaged, this can actually change who someone is.

Tragically, Gage never fully recovered his "original" personality. He struggled to maintain steady employment, even working in a circus as a medical oddity, and passed away in 1860 at the age of 36.

"Information is not knowledge." - Albert Einstein

In the years following Phineas Gage's mind-blowing accident (ha. ha.), scientists started asking more and more questions, and trying to understand, for example, how we process visual information. But then they started getting really intrigued by human intelligence. Why do some brains work like crazy supercomputers? What can explain the fact that at the same time that we have people who can barely do basic math (WHY ARE YOU LOOKING AT ME?), we also have thinkers like Einstein who drop groundbreaking theories out of nowhere? Is this magic, pure talent, countless hours of practice, or a bit of all that? Could the answer lie in the physical brain itself?

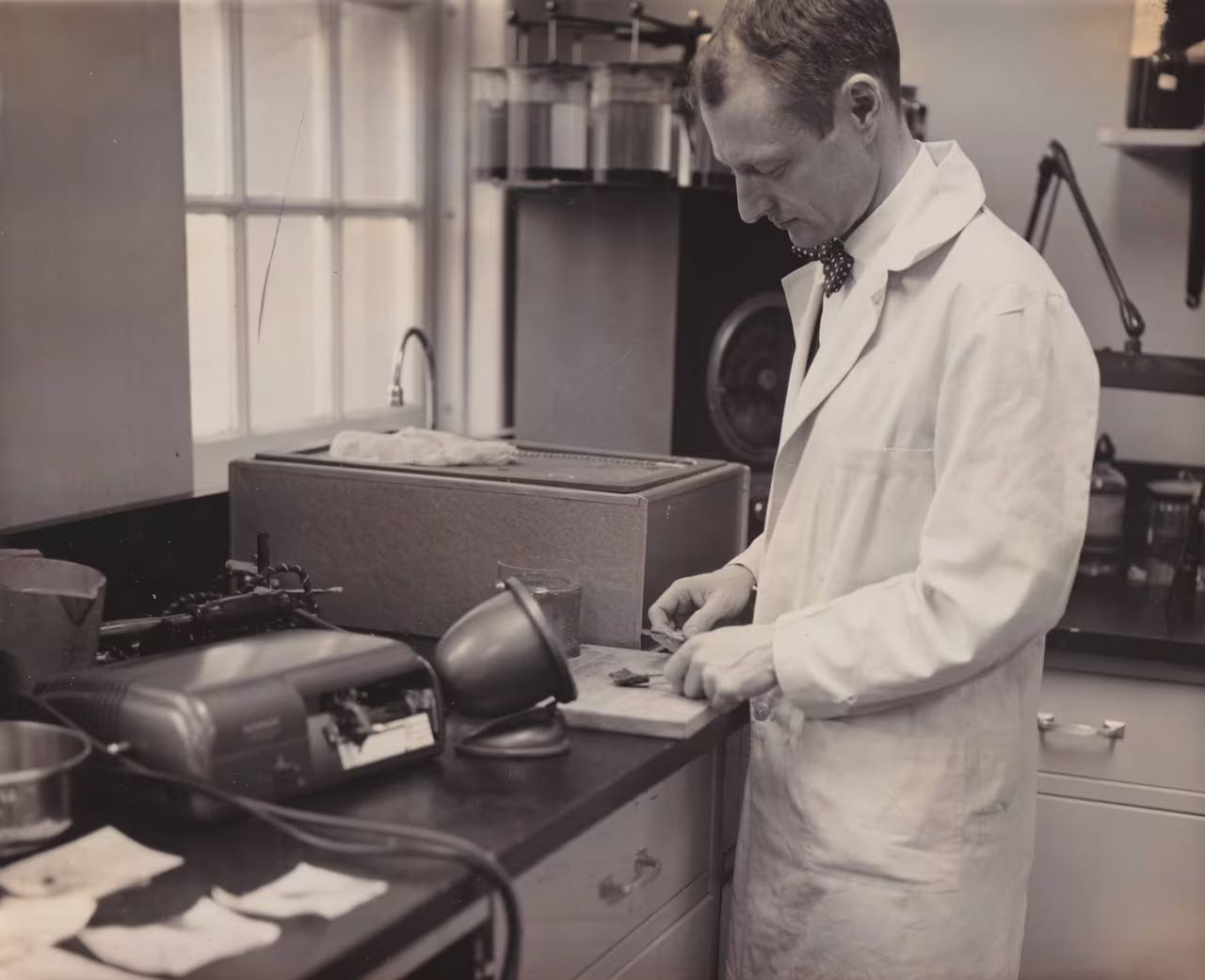

One guy who was particularly eager to find answers was Dr. Harvey, a pathologist at Princeton Hospital.

Thomas Harvey was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1912. Following his great-grandfather's footsteps, he pursued medicine, studying at the prestigious Yale University, where he graduated in 1941. Next up was an internship at Philadelphia General Hospital, followed by a pathology residency at New Haven Hospital. After the war, Harvey became an instructor in pathology and neuroanatomy at the University of Pennsylvania's hospital. By 1950, he'd made assistant director of their Laboratory of Clinical Pathology. Two years later, he took on the director's role for the pathology lab at Princeton Hospital. And it was there, in 1955, that he was handed a super high-profile case: the autopsy of Albert Einstein.

By this time, with such an extensive background, Dr. Harvey was more than used to the demands and protocols of conducting autopsies - slice here, put a few stitches there, fill in a lot of paperwork, then stop for pizza and beers on the way home. You'd expect this man to handle Einstein's with the same meticulous routine, just maybe being a bit more delicate since, you know, it was the remains of one of the greatest scientific minds ever. A little extra care, a bit more discretion, but overall just treating it as seriously as any other autopsy. The problem is, someone probably should've spelled that out clearly for poor Harvey, but apparently, he didn't get the instructions. Instead, he makes the absolute worst call and just randomly decides to take out and keep Einstein's brain. Yep. Oh, and because apparently one souvenir wasn't enough, he also took Einstein's eyeballs, reportedly giving them to the physicist's personal eye doctor, Henry Abrams. Where are these eyeballs now? Apparently, in a safe deposit box in New York City.

And you know what's worse? Harvey did all this without even informing, let alone asking permission from, Einstein's family.

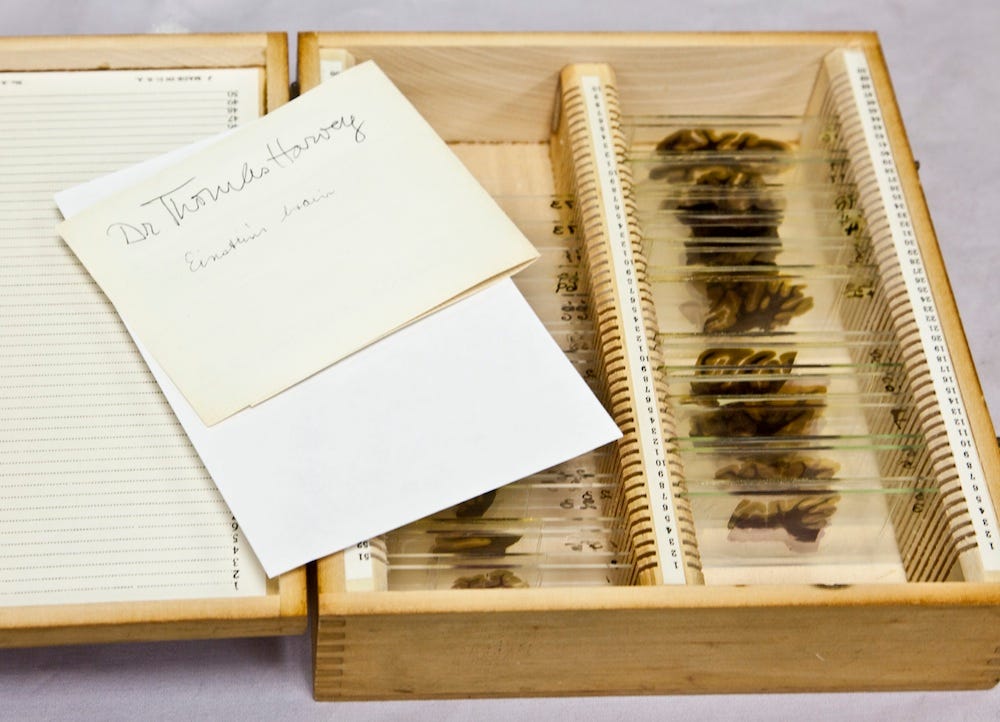

Once the brain was out, the doctor took his time meticulously photographing and dividing it into 170 pieces (a process that took a full 3 months to complete). Then, he carefully immersed each slice in celloidin - a cellulose-based substance - to harden them up for microscopic examination down the road. Harvey's grand aspiration was to quite literally understand the source of Einstein's genius by dissecting his brain, hoping to find something in there, like a golden ticket or whatever, that would answer all of the questions about intelligence the scientists were asking for so long. But Dr. Harvey knew such an undertaking was too massive for one man. So, he decided to assemble a brain trust of sorts and ship those cerebral slices across the country to various experts in neuroscience and pathology. The deal was they'd study their respective Einstein brain bits, report back their findings to Harvey, who was overseeing this questionable endeavor, so that he eventually would compile it all to unveil the big secret to the world.

Dr. Harvey also kept some of the slices to himself and, believe it or not, went on to store them in arguably the most casual way possible: tossed into a box sitting in his own basement, presumably next to the spare toilet paper and holiday decorations.

I know what you're thinking - Harvey's decision to straight-up swipe Einstein's brain was obviously outrageous and unethical as hell. No doubt about it. But the theory he wanted to investigate what he decided to do that didn't just come out of nowhere.

For years, many scientists have subscribed to the idea that there must be specific physical features of the brain that are completely (or, at least, that they play a huge part) responsible for extraordinary intelligence. In fact, some still defend this theory today, but modern research has really cast a lot of shade on those overly simplistic explanations. Leading theories these days point to high intelligence resulting from this complex dynamic between several neurological factors, with a big emphasis on how efficiently information travels through the brain and how different specialized brain regions work together.

Word of this bizarre “adventure” eventually got out, and people were outraged. But despite that, Dr. Harvey eventually did manage to secure permission from one of Einstein's sons to pursue this, promising to publish groundbreaking findings in respected journals very soon. Spoiler alert: this whole "publishing revolutionary studies" part never really materialized. Back on the home front, tensions were rising to a boiling point. Dr. Harvey's wife was, understandably, absolutely furious over the fact that a chunk of Einstein was just casually sitting around their house. Unable to reconcile their differences, our doctor packed his bags and headed for the Midwest.

Ironically, what he probably thought would be a ticket to greater professional recognition and fame turned into a burden, maybe even a curse. In the following years, Harvey lost his prestigious position at Princeton, failed an important exam that cost him his medical license, and saw not one, not two, but three marriages crumble. The once ambitious doctor went from place to place, eventually ending up in Lawrence, Kansas, working on an assembly line at a plastic extrusion factory.

“Curiosity has its own reason for existing. One cannot help but be in awe when he contemplates the mysteries of eternity, of life, of the marvelous structure of reality.” - Albert Einstein

While he turned away most journalist requests for interviews, Harvey did seem to low-key enjoy the chance to show off his prized possession to a select inner circle of fellow Quaker buddies and colleagues.

Here, let him show it to you, too!

A tiny number of research papers did eventually emerge from the handpicked team of investigators, but their findings were pretty much insufficient to actually prove what they initially set out to demonstrate.

In 2014, Terence Hines, a psychology professor at Pace University, took a nice hard look at six of these studies and wasn't impressed by what he saw. During a meeting with the Cognitive Neuroscience Society, he presented a detailed critique, pointing out some of the flaws he could identify. First off, Hines questioned the methods used to examine the brain. Many of these studies, he argued, lacked proper control groups - basically, other brains to compare Einstein’s brain against. Without that, it's hard to say if Einstein’s brain was truly unique or if those features are just common variations. Another big issue was the problem of "cherry-picking" data. Hines suggested that researchers might have been focusing only on the findings that supported their theories about Einstein’s intelligence, while ignoring other data that didn’t fit the narrative. And then there’s the small sample size problem, as Hines pointed out. Basing broad claims about intelligence on the brain of just one person, Einstein or not, is pretty weird science.

Dr. Harvey found himself back in Princeton in the 1990s, where this crazy saga began decades before. After hauling a few pieces of Einstein's brain back and forth across the country from basement to basement for decades, he finally handed over what was left of it to a pathologist at the same University Medical Center where the physicist had passed away. Today, some of those remaining brain pieces are on public display at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia.

So, there you have it. This is our story today, which I hope you have enjoyed! I look forward to reading your comments down below.

And by the way, before I go, just for good measure, let's agree to keep all future scientific discoveries safe, preferably somewhere more secure than inside a cider box stashed under a beer cooler.

Extremely interesting, Marina.

I mean… I had no idea that this whole thing was a whole thing…! I can’t believe slices of Einstein’s brain are on display still, completely disregarding his wishes to not be gawked upon. And his eyeballs in a safe deposit box? Whhaaaa?! Why? So stupid. The whole thing is bizarre. I’d like to steal them all and burn them to ash for the wind to disperse all willy Billy, as per the original owners request. It’s a weird and morosely invasive material possessiveness on grand display. Keeping chunks of his body is a grand disrespect!