The best protection a woman can have is courage.

The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 was a turning point in the fight for women's rights

Picture, if you will, the landscape of mid-19th century America, a period brimming with social and political change, on the cusp of an epic transformation. In the midst of all this chaos, a game-changing event happened. Often hailed as the birthplace of women's suffrage in America, the Seneca Falls Convention was a historic gathering held in July 1848 at Seneca Falls, New York, marking the first official gathering solely dedicated to discussing women's rights.

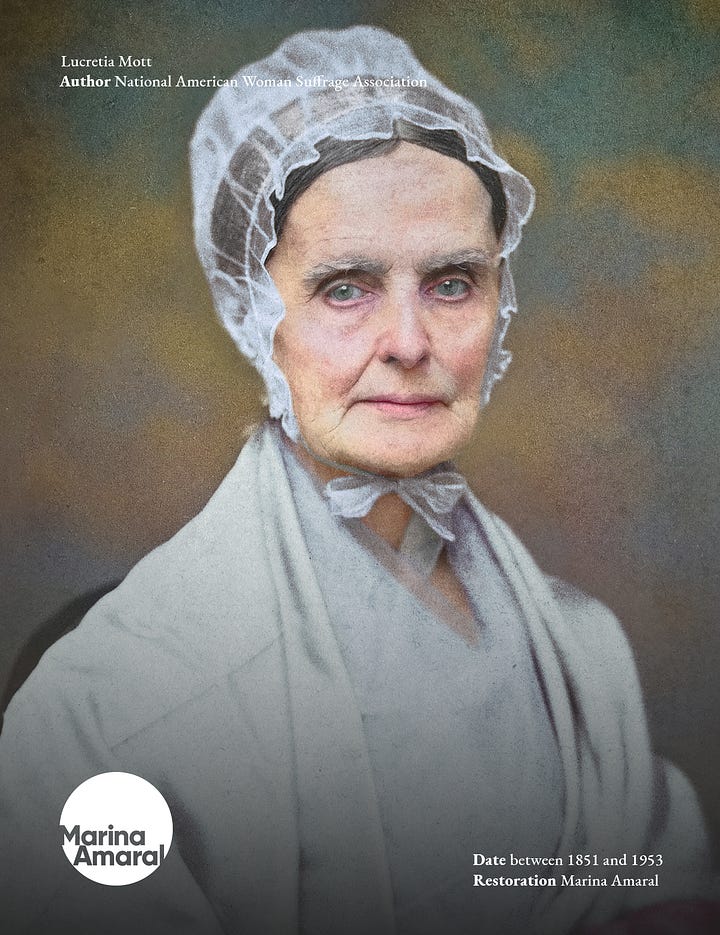

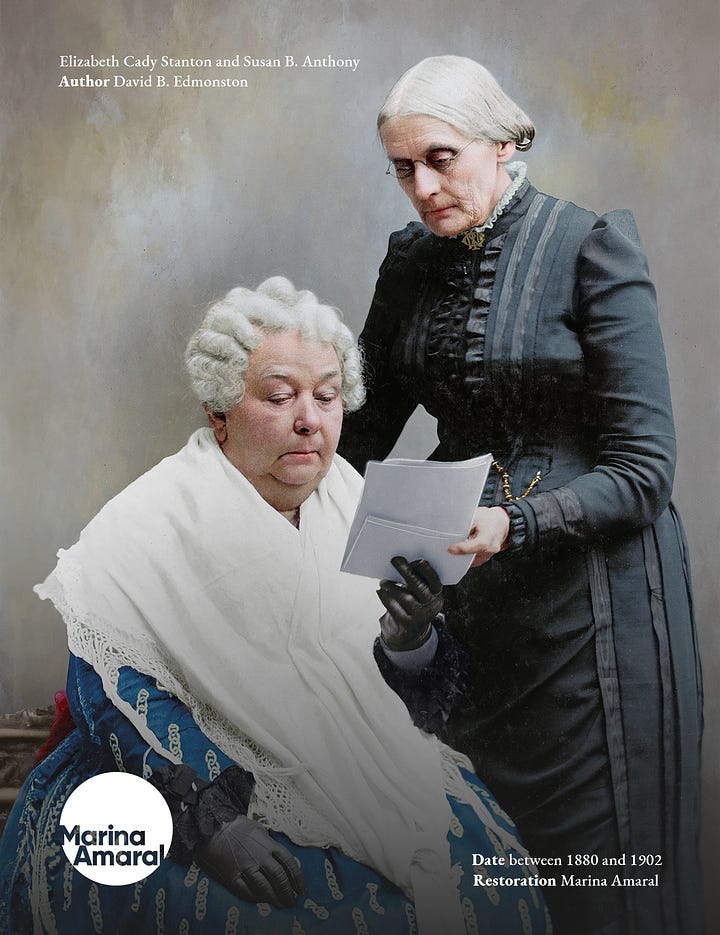

The convention was largely the brainchild of two women who, in many aspects, were ahead of their time: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. Their shared indignation was ignited at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London back in 1840 when they were denied participation solely because they were women. There, Stanton, armed with her sharp intellect, and Mott, fortified by her extensive involvement in the abolitionist crusade, formed an alliance that would trigger a historical domino effect. In an era when women were confined to domestic roles, they dared to envision a world where women transcended these boundaries to shape their own destinies.

“Any great change must expect opposition, because it shakes the very foundation of privilege.” - Lucretia Mott

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, accompanying their husbands, were among American delegates who made the long journey across the Atlantic to join the World's Anti-Slavery Convention in London, in 1840. They represented different American anti-slavery organizations and were fully committed to contributing to a cause they deeply believed in. Upon their arrival, however, they were greeted with an unexpected and unfortunate situation.

When the convention kicked off, a big disagreement sprouted about how involved women delegates could be. A hefty chunk of male delegates felt that having them participating on par with men in such a public forum was both inappropriate and distracting from the main issue of abolition. George Bradburn, an American abolitionist, was one of the few that went the opposite way, strongly advocating for the inclusion of women and highlighting the injustice of their exclusion:

“What a misnomer to call this a World’s Convention of Abolitionists, when some of the oldest and most thorough-going Abolitionists in the world are denied the right to be represented in it by delegates of their own choice.”

Due to cultural norms and religious convictions swaying most votes towards segregation, his plea fell on largely unresponsive ears.

Minister Henry Grew, a delegate whose daughter was among the excluded, argued that involving women in the convention was a violation of both English customs and divine law. Once the discussion was over, the women were relegated to a separate gallery, isolated from the main proceedings.

The feeling of being excluded and marginalized had a significant impact on Lucretia, Elizabeth, and the other women who were there. They were strong supporters of freedom and rights for others, yet they experienced silence in the very place where they aimed to advocate for liberty. Stanton, later recalling this incident that highlighted the blatant hypocrisy and sexism even within progressive movements, emphasized the deep sense of injustice it installed in her. She also remembered that she and Lucretia "walked home arm in arm," that day, determined to hold a women's rights convention as soon as they got home.

And just like that, a still vague idea for what would eventually be the Seneca Falls Convention was born.

Stanton, Mott, and their allies recognized they had to carve out a space for women's issues to be freely and openly debated if they wanted any shot at effectively battling for women's rights - free from the chokehold of bias that had silenced them back in London. Despite the immediacy of their resolve, it would take eight years for the idea to come to fruition.

“The more I think on the present condition of woman, the more am I oppressed with the reality of her degradation. The laws of our Country, how unjust are they!—Our customs how vicious! What God has made sinful, both in man & woman,—custom has made sinful in woman alone."

- Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott was raised in a Quaker household, following a religion that preached equality of all people under God. She once remarked, "Among Quakers there had never been any talk of woman's rights—it was simply human rights. I grew up so thoroughly imbued with woman's rights that it was the most important question of my life from a very early day."

Elizabeth, born into the prosperous Cady family of Johnstown, New York, was known for her rebellious spirit from an early age. This strong sense of independence became particularly evident in an incident during her school years, when an English teacher assigned her to read 'The Wife' by Washington Irving. The poem's metaphor of a wife as a vine clinging to an oak tree, representing her husband, struck a nerve. In a moment of bold indignation, Stanton ditched the poetry book mid-class and left crying out of sheer outrage. She later challenged her teacher about this offensive depiction of women which she found utterly degrading. During a time when women were mostly limited to domestic duties and had limited to no involvement in public discussions, such actions were revolutionary.

“Remember the dignity of your womanhood. Do not appeal, do not beg, do not grovel. Take courage, join hands, stand besides us, fight with us.” - Christabel Pankhurst

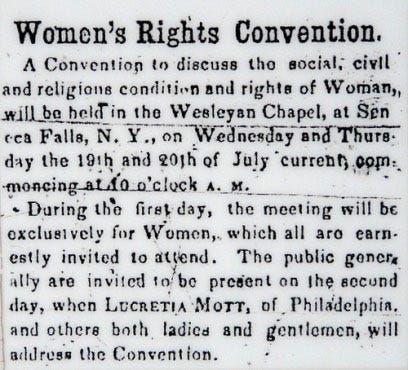

Those women were fully aware of the mountain they had to climb. A convention for women's rights, they knew, would be perceived as nothing less than radical, even controversial, and likely to stir a whirlwind of criticism from everywhere. Yet, they pressed on. Their announcement in the Seneca County Courier on July 14, 1848, was simple and very straightforward: 'A Convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman will be held in the Wesleyan Chapel at Seneca Falls.' The reactions varied widely - from cheerleaders who couldn’t wait for it to start to cynics throwing shade their way.

Scheduled for July 19 and 20, 1848, the event was organized in a relatively short amount of time. The organizers made a deliberate choice to dedicate the first day solely to women, creating a safe space where they could openly and honestly discuss their experiences and perspectives and voice their opinions. The second day was open to the public, including men.

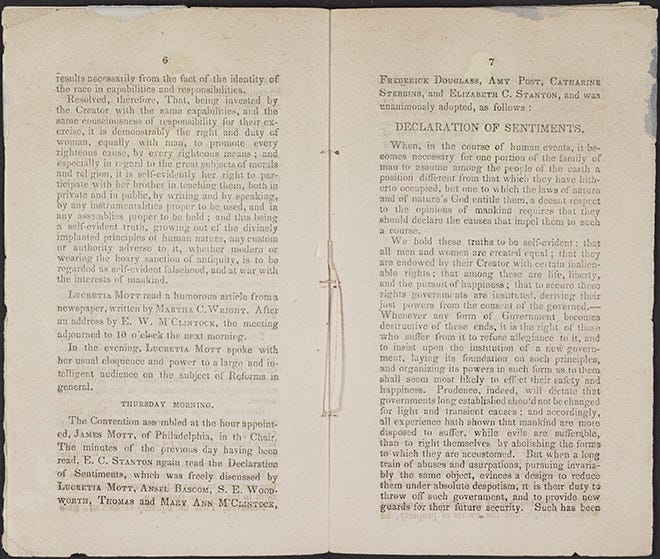

On July 16, Lucretia Mott, Martha C. Wright, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Mary Ann McClintock gathered at the M'Clintocks home to organize the agenda, assembling the speeches and framework for the meeting. The centerpiece of their planning was the Declaration of Sentiments, a document written primarily by Stanton. Drawing inspiration from the Declaration of Independence from 1776, Stanton reimagined it as a powerful statement advocating for women's rights. By changing a few words, she drew a parallel between the struggles of the Founding Fathers and those of the women's movement, effectively framing women’s fight for equality as an extension of the American ideals of liberty and justice.

In the midst of these earnest preparations, a rather comical scenario unfolded with Elizabeth’s husband, Henry Stanton. As someone aspiring for political office, Henry conveniently decided that the best way to support his wife's groundbreaking convention was to be anywhere but Seneca Falls. This retreat to safer grounds was emblematic of the times. Like a true gentleman of the era, Stanton was not exactly enthusiastic about granting women voting rights, much less voicing opinions in public. His evasion provided a perfect illustration of the mindset the convention was up against: revolutionary ideas are all well and good, as long as they don’t upset the status quo too much.

As the convention date approached, Elizabeth confessed her anxiety, admitting she was feeling like "abandoning all her principles and running away."

But now, there was no turning back.

“Men—their rights and nothing more; Women—their rights and nothing less.” - Susan B. Anthony

On July 19, 1848, the Wesleyan Chapel was packed to the rafters. At eleven o'clock, a determined 32-year-old Elizabeth stood before the crowd, ready to shed light on an issue long relegated to the shadows. She declared that a sense of “right and duty” propelled her and her friends to champion the cause of women's rights, and asserted that only women could fully comprehend the extent of their oppression. She passionately urged every woman present to reclaim her life and confront the norms that held them back. Then, she voiced the iconic phrase:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men and women are created equal.”

This marked the introduction of the Declaration of Sentiments, outlining ways in which women were systematically stripped of basic rights like voting or accessing quality education and legal representation. Each point Stanton read out stirred thought-provoking discussions prompting potential amendments. The proposition of women's suffrage ignited a heated debate.

The Seneca Falls Convention was not the first time that women took inspiration from the Declaration of Independence to champion their rights. In April 1848, for instance, forty-four married ladies wrote sarcastically to the New York State legislature: "your Declaration of Independence declares, that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed. And as women have never consented to, been represented in, or recognized by this government, it is evident that in justice no allegiance can be claimed from them. . . . Our numerous and yearly petitions for this most desirable object having been disregarded, we now ask your august body, to abolish all laws which hold married women more accountable for their acts than infants, idiots, and lunatics."

During the nineteenth century, women faced not only restrictive but also perplexing and bizarre legal circumstances in the United States and other parts of the world.

Take the concept of coverture, for example. This lovely legal principle basically ended a woman's legal existence when she married. Her property, earnings, and even identity were swallowed up by her hubby. Engaging in business or signing a legal contract without a man's nod of approval? That was as unthinkable as it gets. Employment laws were another gem. Women were graciously allowed to work in roles befitting their delicate nature – think sewing, teaching, and other 'feminine' jobs. And, of course, they were paid a pittance compared to men, because why should equal work mean equal pay? Women serving on juries was a concept so wild that it took until the 1960s and 1970s for all states to allow it. The courtroom, it seemed, was too sacred a place to be sullied by female reasoning – or perhaps the legal system just couldn't handle the idea of a woman passing judgment on a man. Fashion rules didn't escape this madness either. Up until 1993 (!!!), women wearing pants on the U.S. Senate floor were frowned upon. Because, of course, a woman's ability to legislate and govern could surely be impeded by the scandalous act of wearing trousers. And let's not forget that for the longest time, getting a divorce was significantly more challenging for women, requiring them to prove more than just irreconcilable differences. This meant that many women were trapped in unhappy, and often abusive, marriages.

A new chapter begins

On the convention's second day, even more people showed up than on day one. Among them was Frederick Douglass, the only African American present.

Douglass had strong oratory skills. Speaking in favor of the cause, he pointed out the injustice and societal loss that occurs when women are denied the right to participate in government. According to him, it not only degrades women but also hampers and rejects half of the moral and intellectual power that should govern our world. “In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens,” he argued, “but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world."

The atmosphere within Wesleyan Chapel must have been electric as further discussions of the Declaration of Sentiments unfolded. The floor was opened to comments from various individuals, each offering their unique perspectives in a discussion that ultimately led to unanimous acceptance of the Declaration. In total, 100 out of the 300 attendees, comprising 68 women and 32 men, signed the document.

"If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them." - Sojourner Truth

The organizers couldn't have predicted it, but the impact of the Seneca Falls Convention joined the chorus and went far beyond the humble walls of the Wesleyan Chapel. People of all genders came together across America to advocate for tangible changes. Struggles for gender equality were simultaneously unfolding in various parts of the world. The UK had its own wave of activism building up, even though things wouldn't heat up until the suffragettes stepped in during the early 20th century. Over in France post-1848 Revolution, ladies like Jeanne Deroin and Pauline Roland stood up tall for voting rights, education access and better working conditions. Scandinavian countries, too, were witnessing the beginnings of their women's rights movements.

But it wasn't always smooth sailing or consistent progress everywhere.

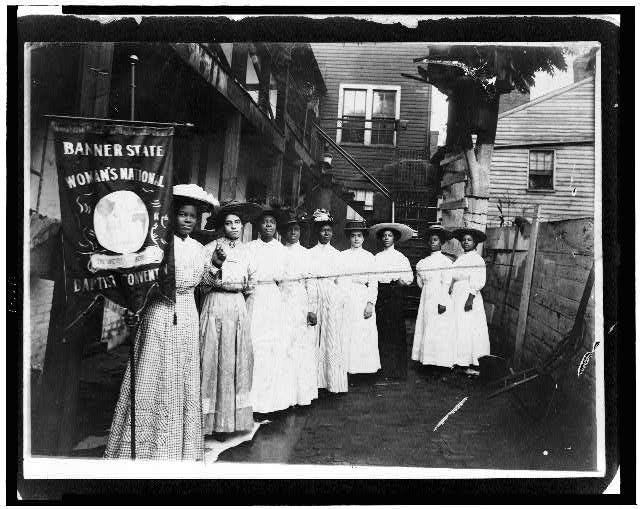

The fight for civil rights is not a straightforward journey and it's important to recognize that these movements, even when working towards the same or similar goals, face challenges due to the diverse experiences, beliefs, and ideologies of their participants. This complex dynamic can be seen in action during the post-Civil War period in the United States: the 15th Amendment in 1870 was a huge win because it let African American men vote, but Black women were still left out of these gains. This lack of validation and representation was replicated at the Seneca Falls Convention, where not a single Black woman was present. Although the event claimed to champion the liberation of all women, it similarly faltered in its commitment to racial equality. This racial divide also popped up in the suffrage parades, where Black women were often required to march separately from their white counterparts. Even Susan B. Anthony – major player in the suffrage movement – had some very questionable views on this matter. In a conversation with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, she once stated, 'I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman.'

This period saw women like Harriet Tubman, Ida B. Wells (who famously refused to march at the back of the 1913 suffrage parade in Washington, D.C.) and Mary Church Terrell emerge as powerful voices in both the suffrage and civil rights movements, tirelessly advocating for change.

Their efforts, along with those of countless others, culminated in a significant milestone in 1920 when women in America finally secured the right to vote, a whopping seventy-two years after the Seneca Falls Convention. But this victory was just the starting point in redefining how society views women and what they're capable of.

“The right is ours. Have it we must. Use it we will.” - Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Every historical account is influenced by the biases and perspectives of those who tell it. When it comes to the women's suffrage movement, just like any other narrative, it has been shaped by those who had the means and opportunity to document it. Unfortunately, this often resulted in critical perspectives and voices being overlooked or excluded. I must admit, with a sense of shame, that it was only recently that I came to realize that the narrative I knew of the women's rights movement was not universal, as it failed to include or even mention the experiences of Black women, who were simultaneously battling for recognition of their rights both as women and as human beings. This reminded me of how selective our collective memory can be. We're okay with an Instagram-perfect version of history that filters out uncomfortable truths for something more pleasing but less real. In this watered-down take, there isn't much room for complexity or internal conflicts - things that are central to any major social change.

Anyway, the journey that began at Seneca Falls continues, and its end is still somewhere on the horizon, waiting to be reached. But this journey, like any exploration into the past, isn't just about where we're going; it's also about what we choose to bring along. It's about looking at that old family photograph and wondering who else should have been in the picture, what stories we might have missed, and realizing that sometimes, what's outside the frame can be just as important as what's within it.

Discover the inspiring stories of extraordinary women who have paved the way towards equality in my latest book, A Woman's World!

It would really be something if women had the first damn clue what they have already given up in this misunderstood effort. The challenges women face today are not the same ones their grandmothers did. Get that. Giving up what it means to be a woman to 'compete in a man's world' has been an unmitigated disaster. Ask any guy how difficult it is to find a female friend...let alone a mate....who isn't constantly frustrating them by unjustly judging what it means to be a man (like a woman would or should know that) and you soon come to recognize the women of today are just not very desirable. In this 'we've been treated unfairly' mode they are arrogant, judgemental, prejudiced, jealous, selfish, petty, unwomanly, overtly sexualized, aggressive, greedy, and terribly insecure. Women of today are like feminized robots. What could possibly be attractive about a package of that?! Of the thousands of women I have met only a handful could I term a genuine woman, and when you meet one, Wow! They are gracious, sensitive, intelligent, forgiving, nurturing (feminine), dignified, beautiful, loving, discrete, wise, and in absolute possession of the magic of what it means to be a woman. And to cover all the bases, a real man is kind, gentle, forgiving, understanding, patient, reliable, selfless, nurturing (masculine), trusting, fearless, devoted, protective, and in full possession of his responsibility to support the rights of women to become what they really are: incredible and unique. Too bad they're almost extinct. The course women have been cajoled into pursuing has brought about the end of everything good between us. I am a single man and almost hopeless in that regard.

Thanks for sharing these stories!