Siegfried Sassoon: A Poet's Journey Through The Great War

But death replied: “I choose him.” So he went, And there was silence in the summer night."

World War I marked a turning point in human history. From 1914 to 1918, as Europe's major powers were entangled in a web of alliances, millions of people were either killed or wounded as a result of this catastrophic conflict. These tumultuous years reshaped nations, redefined global politics, and forever affected countless individuals' emotional states and psyche. Amid the echoes of gunfire and explosions, stories of immense courage and profound despair and trauma emerged. Trenches became graves for the fallen - and there were many. Gas attacks left soldiers gasping for breath. Men faced not only the enemy's bullets and violence but the gnawing cold, hunger, and the constant threat of disease. Each day on the frontlines brought with it gruesome sights of mangled bodies often being scavenged by rats, and the haunting screams of the dying, friends and foes alike, challenging the very essence of humanity.

These tales were not just those of generals, politicians, or nations as a whole; they were deeply personal chronicles of soldiers, nurses, and ordinary civilians.

Siegfried Sassoon, a singular voice of raw emotion, emerged in this backdrop of unprecedented chaos and devastation.

His powerful poems about the brutality of the First World War challenged the prevailing narratives and propaganda of the times and gave voice to the disillusionment and pain of a generation thrust into the heart of battle.

"(...) and how, at last, he died, Blown to small bits. And no one seemed to care Except that lonely woman with white hair." - The Hero, by Sigfried Sassoon

Early Life

Siegfried Sassoon was born in September 1886 in the village of Matfield, Kent - the second of three children of Alfred Ezra Sassoon, a Jewish man, and Theresa, an Anglo-Catholic woman. Due to their large fortune, the Sassoons were sometimes referred to as the "Rothschilds of the East" (in reference to the Rothschild Family, the most prominent European banking dynasties).

Raised in a privileged household, Sigfried spent most of his pre-war years enjoying a comfortable and relaxed country life, reading and writing poetry, fox hunting, and playing cricket for Kent. He attended Kent's New Beacon School and Marlborough College before joining Clare College, Cambridge, in 1905, which he left a while later without a degree.

“But death replied: “I choose him.” So he went, And there was silence in the summer night."

Encouraged by a wave of nationalism and patriotic fervor, Sassoon enlisted in the Sussex Yeomanry in 1914. However, a riding accident left him with a broken arm, delaying his commission to the Royal Welch Fusiliers until May 1915.

Tragedy struck the same year when his younger brother, Hamo, was killed in the Gallipoli Campaign. Six months later, still recovering from his loss, Sassoon made his way to the front lines in France. That's where he met Robert Graves, a fellow young poet. The two men immediately hit it off and developed a strong friendship, often exchanging and reviewing each other's writings.

During the war in France, soldiers found solace and shelter in cramped dugouts that served as their temporary homes. In these confined spaces, they sought moments of rest, wrote heartfelt letters to loved ones far away at home, and shared stories to divert their minds from the constant threat surrounding them. These trenches and dugouts silently witnessed their deepest fears and greatest hopes, and also bore witness to some of the most devastating battles of the war.

The Battle of the Somme and the Battle of Verdun stand out as particularly horrifying clashes during that period. In 1916, the Somme alone saw an unimaginable number of casualties, with more than a million soldiers either wounded or losing their lives. Meanwhile, Verdun witnessed French and German forces locked in a brutal struggle that resulted in an estimated total of 700,000 casualties for both sides combined.

For numerous soldiers, battles such as The Somme and Verdun represented the sheer pointlessness of the entire war. It became a heartbreaking routine to witness close friends, sometimes even family members, die. Every day, many who ventured into the hostile territory of no man's land were ruthlessly slain by the onslaught of machine gun bullets.

And the war's horrors didn't end there, as the introduction of chemical warfare brought unprecedented terror to the battlefield.

A British officer described the effect of the gas on French colonial soldiers the first time it was effectively used in battle, on April 22, 1915, at 5.pm:

“A panic-stricken rabble of Turcos and Zouaves with gray faces and protruding eyeballs, clutching their throats and choking as they ran, many of them dropping in their tracks and lying on the sodden earth with limbs convulsed and features distorted in death.”

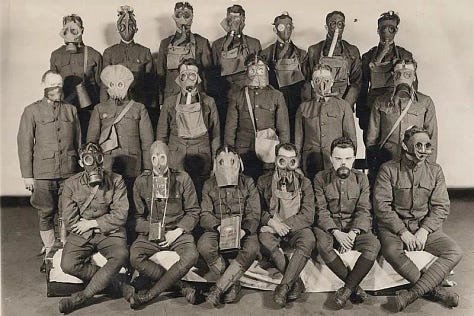

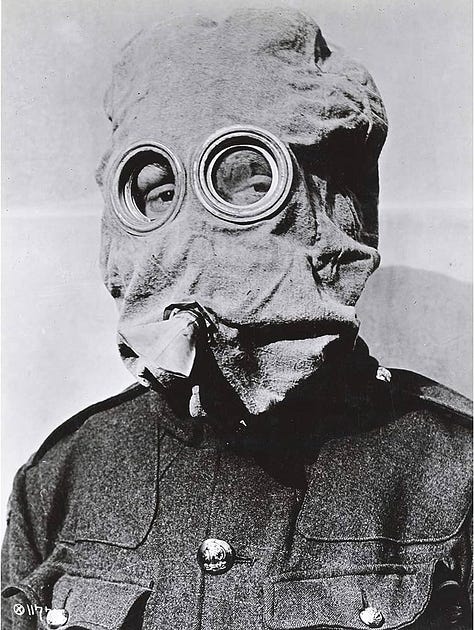

“There was no technology to protect the soldiers from this new weapon; an operational gas mask was not available, so the Allied soldiers improvised with linen masks soaked in water and “respirators” made from lint and tape.” Source

Soldiers would be filled with panic as they saw the gas clouds advancing towards the trenches. The haunting screams and desperate gasps for air from those who couldn't secure their masks in time served as horrifying reminders of the ever-changing brutality of war. This new aspect of warfare added an extra layer of horror to the daily traumas these young men had to endure.

These experiences deeply impacted Sassoon. One of his poems from that time, titled "The General," vividly portrays his growing disillusionment with those in charge:

“Good-morning, good-morning!” the General said

When we met him last week on our way to the line.

Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of 'em dead,

And we're cursing his staff for incompetent swine.

“He's a cheery old card,” grunted Harry to Jack

As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack.

But he did for them both by his plan of attack.

“Mad Jack”

Sassoon's fearless bravery in action earned him quite a reputation. Among his most astonishing feats was capturing a sixty-strong German trench all by himself, after which he casually sat down and started to read a book of poetry. That made him lose track of time and forget to report back. An attack on Mametz Wood was unintentionally delayed by two hours as a consequence because it was still believed that there were British patrols out. Colonel Stockwell, who was in command at the time, was not pleased and supposedly exclaimed: "I'd have got you a DSO (Distinguished Service Order) if you'd only shown more sense."

Sassoon often participated in missions that others viewed as extremely dangerous, and near suicidal. On one occasion, he fearlessly faced relentless gunfire to rescue a wounded soldier—a courageous act that earned him the prestigious Military Cross.

Some people speculate that his apparent disregard for death might have been influenced by severe depression during this period, which could explain why he took such extreme risks. This combination of bold bravery and perceived recklessness led to him being nicknamed "Mad Jack."

“In winter trenches, cowed and glum, with crumps and lice and lack of rum, he put a bullet through his brain. No one spoke of him again."

As time passed and weeks turned into months, the burden of the war weighed heavily on Sassoon's mind. His writings during this period became increasingly filled with a sense of heaviness.

Tragedy came too close again when 20-year-old David Cuthbert Thomas, with whom the poet had had a romantic relationship before the war, was hit by a shot in the throat and tragically lost his life as he choked on his own blood. This devastating loss deeply affected Sassoon and served as inspiration for some of his most powerful poems that followed. In 1916, he returned to England to recuperate from an illness. However, as his recovery leave came to an end, it became evident that the impact of war extended beyond physical wounds. The accumulation of witnessing immense loss and violence had profoundly shaken him to his very core, leading him to refuse further duty.

The war had transformed him profoundly, and he was on the verge of taking a firm stand against it.

“On behalf of those who are suffering now, I make this protest against the deception which is being practiced on them.”

Fueled by frustration over the war's senselessness and encouraged by pacifists such as Lady Ottoline Morrell and Bertrand Russell, Sassoon wrote a powerful letter, "Finished With The War: A Soldier's Declaration", straightforwardly criticizing the government's motives for prolonging the war and calling out the prolonged suffering of soldiers for insincere political reasons. The letter was read before the House of Commons on July 30, 1917, and printed in The London Times on July 31, 1917.

“I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority, because I believe that the War is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it. I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe this War, upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation, has now become a war of aggression and conquest.” (Link to letter)

The military's typical response to such an act would be a court-martial, and many expected that Sassoon would face this consequence. However, his friend and fellow poet Robert Graves intervened. Graves made a case for Sassoon's mental state, suggesting that he was grappling with shell shock, a term used back then to describe post-traumatic stress from battle. Whether this was a true reflection of Sassoon's condition or not is still unclear. In any case, Graves’ appeal worked. Sassoon was sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital.

During his time at Craiglockhart, Sassoon met a young officer named Wilfred Owen, an aspiring poet who greatly admired Sassoon's literary work. Their shared experiences of war, combined with a mutual love for poetry, forged a strong bond between them. Sassoon took on the role of mentor to Owen, offering guidance and support in refining his written works during their time together at the hospital. The affectionate tone in Owen's later letters to Sassoon indicates a strong bond between them, although the exact nature of their relationship remains a topic of debate.

One of these letters, written on November 5, 1917, reads: “You have fixed my Life—however short. You did not light me: I was always a mad comet; but you have fixed me. I spun round you a satellite for a month, but I shall swing out soon, a dark star in the orbit where you will blaze.” In another one, undated, Owen says: "I can't help feeling that I belong to you more than to anyone else in the world."

While never openly declaring himself gay, Sassoon had relationships with both men and women throughout his life. Max Egremont's biography of the poet describes his relationship with artist and cross-dressing socialite Stephen Tennant, whom Sassoon fondly describes as "the most enchanting creature I have ever met". In 1921, he embarked on a love affair with Prince Philipp of Hesse.

Tragically, Wilfred Owen lost his life while crossing the Sambre Oise Canal near Ors on November 4th, 1918.

The war ended one week later.

Post-war life and legacy

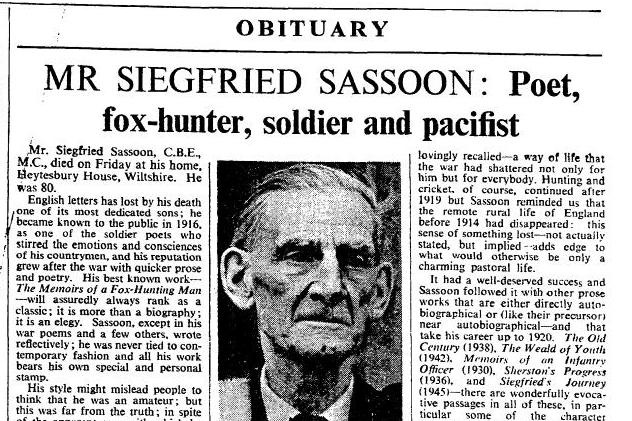

After the war, Sassoon continued to pursue his literary interests. He briefly engaged in politics, worked as a literary editor at the Daily Herald, and traveled across the United States and Europe. In 1928, he anonymously published the first volume of a fictionalized autobiography that eventually became a classic, “Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man”, followed by “Memoirs of an Infantry Officer” (1930) and “Sherston's Progress” (1936). Later, he wrote an actual autobiography titled “The Old Century, The Weald of Youth and Siegfried's Journey”.

In December 1933, he married Hester Gatty. Their son, George Sassoon, was born three years later, in 1936. The couple eventually split up after World War Two. It is said that Sassoon wrestled with finding a balance between his fondness for solitude and his longing for companionship.

Despite remaining connected to literary circles throughout his life, Sassoon spent much of his later years in quiet seclusion. He passed away from stomach cancer in 1967, just one week shy of his 81st birthday.

His legacy lives on.

Exciting News!

Invited by my good friend Paul Reed, I'm about to embark, in the first week of September, on a unique journey that I'm thrilled to share with you all: the War Poets Tour, promoted by Leger Holidays! This awesome adventure, of which I'm very grateful to be a part, will allow me to dive even deeper into the stories of Siegfried Sassoon and many other soldiers who used the power of poetry to capture the war experience.

Sassoon's story is just one of many, and over the next couple of weeks, I'll be sharing the life stories of two other incredible war poets here. I'm very excited and eagerly anticipate sharing every moment of the tour with you. It's going to be amazing. So subscribe, and stay tuned!

To learn more about the War Poets Tour and many others, visit the website of Leger Holidays.

The horrors of World War Two, particularly the concentration camps and nuclear bombs, are far more familiar to most people. However, World War One was itself an unspeakable nightmare, and as you noted above, it "marked a turning point in human history." Thank you for sharing.

Incredibly sad and profound stuff. Thank you for writing and sharing this.