No marathon was more chaotic than the 1904 St. Louis Olympics

I'M BACK! And ready to tell you about the most ridiculous race in Olympic history

HELLO!!

I know, I know, it’s been a while…

Let’s just say that a lot of not-so-great things happened in the past few months, which kept me away longer than I planned. But I’ll save that drama for another day. The good news is that I'm fine, and I’m back. And I figured my return needed a bizarre story (because why not?)

So, that's what I have for you! Today’s story is about the 1904 St. Louis marathon, which somehow managed to involve runners dodging angry dogs, choking on dust, collapsing from exhaustion, and even drinking poison just to keep going.

Thank you guys for sticking around while I've been away. I'm very happy to be back and excited to continue obsessing over history with you!

“The most important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning but taking part; the essential thing in life is not conquering but fighting well.” – Pierre de Coubertin (founder of the modern Olympic Games)

Every four years (except when there’s a global pandemic), most of us stop everything we are doing to watch insanely fit people run, jump and swim. We call it the Olympics, and it’s a big deal. Like, billion-dollar stadiums and “Olympic Village” condom shortages kind of big deal.

This time around, in 2024, Paris was the center of attention (along with that weird mascot nobody could quite figure out). Simone Biles, as expected, killed it in gymnastics. But the best moment for me, as the shamelessly proud Brazilian that I am, no doubt, was when Rebeca Andrade nailed her floor exercise routine and won the gold. I was out of my mind. Totally insane, shouting at the TV and jumping up and down on the sofa (Brazil is usually on the news for something embarrassing, so let me have this one, okay?) I love Simone, but outshining her WAS AMAZING.

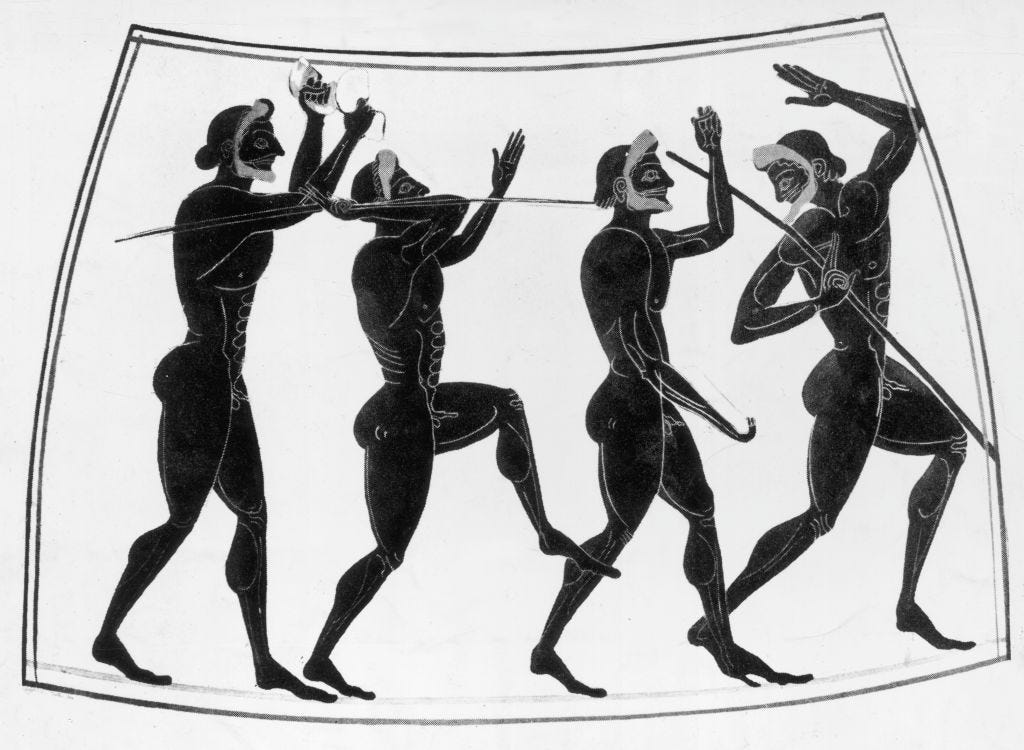

Before Rebeca and Simone, though, the Olympics had a whole different vibe. For example, only men were allowed. And yeah, sometimes those men were naked.

While we may not know every detail, most historians agree that the first recorded Olympic Games were held in 776 B.C.E. in Olympia, Greece. They started as a religious festival honoring Zeus, but quickly transformed into a massive event, attracting thousands of people every four years to join in the celebrations (which included ceremonies and the gruesome, horrible sacrifice of 100 oxen at the Altar of Zeus. Lovely.). A “sacred truce”, or “Ekecheiria”, which put wars on hold during the festivities, ensured that everyone could travel safely, watch or compete, probably drink too much wine, and then head home to resume their usual hostilities once the party was over.

The first and only competition during this time was the stadion, a short sprint of about 192 meters, named after the stadium that housed the race. The program gradually included more competitions, such as the diaulos (a 400-meter race), the dolichos (a long-distance race), and the pentathlon (a combination of running, long jump, discus throw, javelin, and wrestling). By 708 B.C.E., combat sports were introduced, starting with wrestling (and its naked athletes), followed by boxing in 688 B.C.E., and the infamous pankration by 648 B.C.E. This thing was brutal, and pretty much had no rules: competitors could punch, kick, choke, and even break bones. The only things off-limits were biting and eye-gouging (you gotta draw the line somewhere, obviously!)

For over a thousand years, things were fine... until the rise of Christianity changed everything. In 393 A.D., Roman Emperor Theodosius I issued a decree banning all pagan festivals, including the Olympics. Game over.

Fortunately, they would make a comeback. But in a way that the original participants - naked and oiled up - would not even recognize.

"In the name of all the competitors I promise that we shall take part in these Olympic Games, respecting and abiding by the rules which govern them, in the true spirit of sportsmanship, for the glory of sport and the honour of our teams."

Pierre de Coubertin, this big-mustache French aristocrat, historian, and sports fanatic, is the guy we have to thank for bringing the Olympic Games back. Inspired by British educator Thomas Arnold, who emphasized the role of physical activity in building moral character and discipline, Pierre firmly believed that sports could - and should - serve a bigger purpose other than just getting a bunch of sweaty people together. “Wars break out because nations misunderstand each other.” he stated, “What better means than to bring the youth of all countries periodically together for amicable trials of muscular strength and agility?”

And what better way to put this to the test, he thought, than by bringing back the most important sporting event in history?

Coubertin spent years traveling across Europe, meeting with educators, politicians, and sports enthusiasts, trying to convince them that this was actually a good and promising idea. In 1892, he organized a meeting at the Sorbonne in Paris, but most people probably thought he was a bit crazy and didn’t take him seriously. Two years later, he gave it another shot with a second conference at the Sorbonne. This time, his persistence paid off. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) was officially established, and they set the date for the first modern Olympic Games to be held in Athens.

“O Sport, You are Peace!”

From April 6 to April 15 in 1896, the first modern edition of the Games finally happened. One of the coolest moments was the debut of the marathon, inspired by the (probably exaggerated) story of Pheidippides, the Greek messenger who supposedly ran 25 miles from Marathon to Athens to announce victory over the Persians.

The second edition was held four years later, in 1900, in Paris. There, women were finally allowed to compete for the first time - though only in a few ‘appropriate’ sports like tennis and golf. Still, a win is a win, and British tennis player Charlotte Cooper became the first female Olympic champion, winning both the singles and mixed doubles events (which sounds even more impressive when you consider that she pulled it off while dressed in what looks like an outfit better suited for a Victorian tea party than an athletic competition).

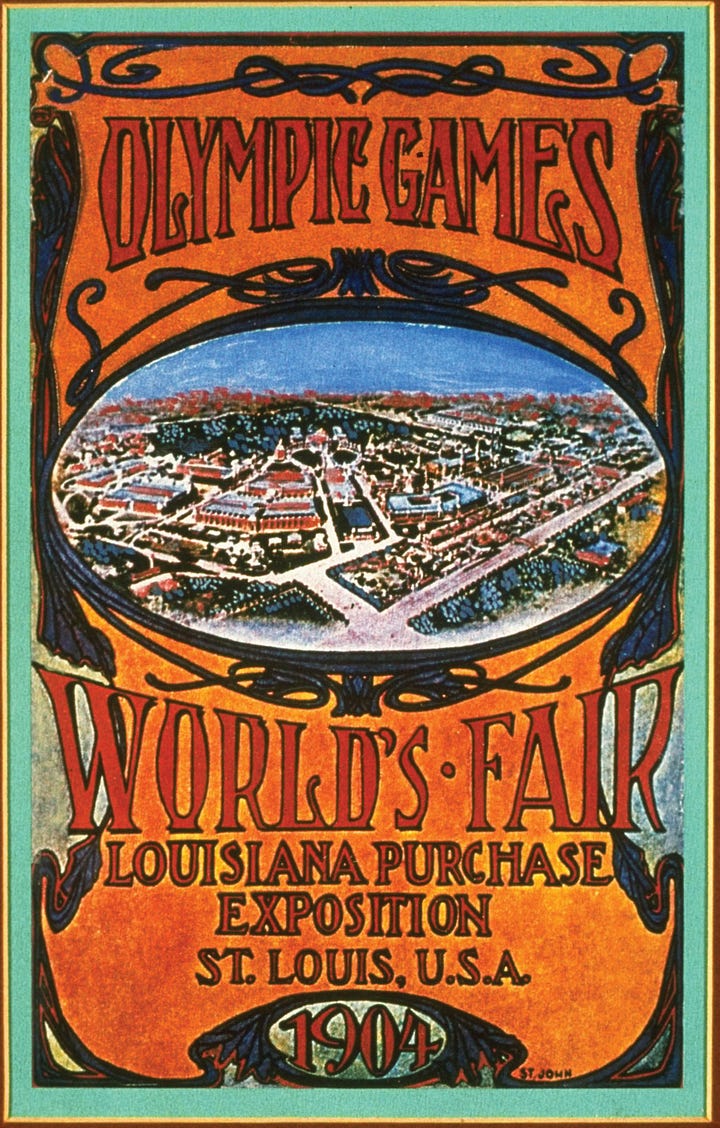

In 1904, it was time to pack up and head to the United States for the first time the event would be hosted outside of Europe. On paper, it sounded great and exciting. But in reality, it was a disaster that started right when St. Louis was chosen as the host city.

The plan had actually originally been to make everything happen in Chicago, but that didn’t sit well with the organizers of the St. Louis World’s Fair, which was already set to take place in the summer of 1904. The team had poured a lot of effort and millions of dollars into planning what was this enormous celebration of the 100th anniversary of the U.S. purchase of the Louisiana Territory. To them, this was supposed to be the main event of the year.

So, like any rational adult would do, these dudes decided to throw a tantrum, threatening to hold their own international sports competition at the World’s Fair if the Olympics didn’t move to St. Louis. The International Olympic Committee, not exactly in a position to call the bluff, freaked out and caved in. The games were relocated, and then shoved into the chaos of the World’s Fair, left awkwardly waving from the sidelines and competing for attention with exhibits, performances, and other attractions. The venues (if you can call them that) were hastily thrown together, often repurposing whatever space was available (such as open fields and lakes), and several events played out in front of near-empty stands. With no promotion, most people had no idea the Olympics were even happening.

Many countries decided it simply wasn’t worth the trouble to send their athletes halfway around the world for an event like that. In the end, only about 650 individuals showed up, and fewer than 100 of those were from outside the U.S. (and half of those were Canadians who probably took a wrong turn on their way to Tim Hortons). To put that in perspective, the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris featured around 10,500 athletes representing 206 National Olympic Committees. The difference is pretty wild.

Pierre de Coubertin, who had already expressed strong dissatisfaction with the decision to relocate the Games, also decided not to attend the event and sent out two IOC delegates (one from Hungary, the other from Germany) to represent him instead. It was probably for the best that he stayed home, because even in his worst predictions, he likely couldn’t have imagined what the organizers would come up with next.

"All sports for all people, that is the new goal to which we must devote our energies." – Pierre de Coubertin

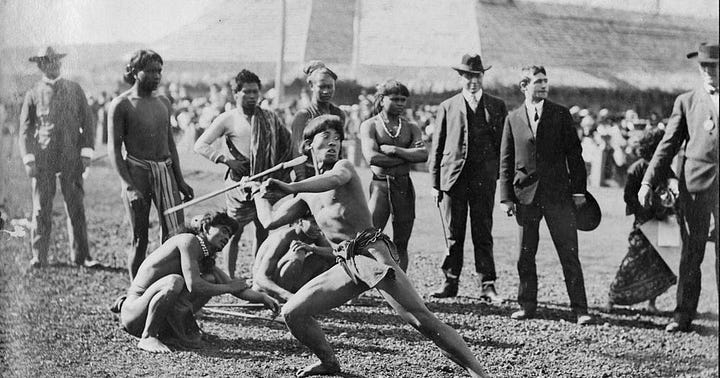

Held on August 12 and 13 under the direction of William John McGee, a prominent figure in American anthropology who somehow convinced himself and others that this was a good idea, the “Anthropology Days” - as they called it - were a series of activities organized to supposedly demonstrate the superiority of white athletes by forcing indigenous people and other non-white groups (many of whom had been brought to the World’s Fair as part of its disturbing “human zoo” exhibits) into athletic competitions they had never heard of before. Literally. Participants were shoved into events like javelin, shot put, and races with zero explanation of what the hell they were supposed to do, and then were made fun of when they didn't do it “right”. I mean, it’s pretty easy to feel superior when you’re the only one who knows the rules, right? Just another case of racism pretending to be science, which was all too common back then.

But if the nasty Anthropology Days weren’t bad enough, things didn’t exactly improve later that month. Because on August 30, with the temperature around 90 degrees, 32 men lined up at the starting line for what would become one of the most ridiculous (and hilarious) marathons ever. Everything started with the course they had to run on, which was made of 24.85 miles of pain wound through uneven, dusty dirt roads (that remained open to traffic even during the competition!) filled with loose rocks, debris and random potholes. Water stations were just two for the entire route (courtesy of a pseudoscientific theory called purposeful dehydration). And then if you were lucky enough not to drop unconscious or dead after the first few miles after inhaling a disgusting amount of dust, you still had to dodge angry dogs, horse-drawn wagons and cars crossing by you along the way.

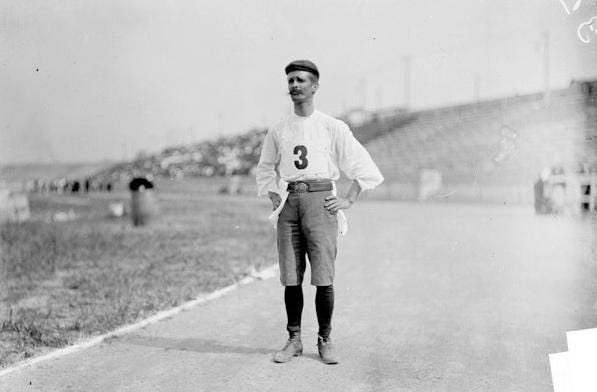

When the starting pistol fired at 3:03 p.m., Fred Lorz, a New York long-distance runner who balanced his career as a bricklayer with marathon training at nighttime, quickly took the lead. Thomas Hicks, one of the more experienced competitors, followed not far behind, joined by other athletes such as Arthur Newton, a veteran long-distance runner, and Sam Mellor, who had previously won the Boston Marathon. Félix Carvajal, also trying to deliver his best performance, was, without a doubt, the most peculiar figure among the group. A Cuban postman and amateur runner from Havana, he’d heard about the 1904 Olympics and decided he had to be there - never mind that he was nearly broken. This was just a small detail, of course, and he already had a solution for it: he headed to Havana’s central plaza, started running in circles like a madman until he drew a crowd, and then announced he’s off to the United States to win the Olympic marathon. I don't know how, but it worked. The locals, either impressed or just entertained, gave him enough money to get a spot on a boat to New Orleans. But his money didn’t last long. After paying for the boat and arriving in the U.S., Carvajal lost the rest in a dice game and had to hitchhike his way to St. Louis. When he finally made it to the starting line, he looked more like a tourist than a runner: long trousers, a long-sleeved shirt, street shoes, and a beret. Thankfully, Martin Sheridan, an American discus thrower, stepped in and cut off his trousers, turning them into running shorts.

I think it’s safe to say that this was the most relaxed guy ever. Instead of stressing about the race, he treated it like a casual sightseeing tour, stopping frequently to chat with spectators, and also to pick up apples when he spotted an orchard along the route. Unfortunately, though, this was a really terrible decision, because the apples turned out to be rotten, which forced him to lie down under a tree to recover from the cramps.

As the race progressed, the heat, combined with the dust and lack of water, started to have serious consequences. One of the first casualties was William Garcia, a runner from California. Garcia collapsed on the course, suffering from severe internal injuries and bleeding caused by dust inhalation, and was found just in time to be rushed to the hospital. Next, it was time for John Lordan to go down. He began experiencing severe cramping early on and was forced to drop out after a few miles. Arthur Newton soon followed, collapsing exhausted before he could reach the finish line.

Fred Lorz was struggling too, but instead of waiting to be the next one taken away to a hospital, he decided to try a more unusual approach. You know what this guy did? He flagged down a passing car and simply rode in comfort for ten miles. I’M NOT KIDDING YOU. Lorz sat back, relaxed, and even WAVED at the other runners as he passed them by. A few miles from the stadium, he hopped out and rejoined the race on foot, casually crossing the finish line as if he’d just won the marathon. The crowd went wild, cheering for what they thought was a legit victory. But then the truth came out. Lorz was confronted, tried to play it off like it was some kind of joke (nobody was laughing) and was quickly disqualified (he was also banned for life, but this ban didn’t stick and was later lifted.)

Yes, you must be asking yourself if I’m making this all up, but I swear that I’m not - and it’s far from over. Now, it was Thomas Hicks who was on the verge of collapse.

"Never in my life have I run such a tough course.” - Thomas Hicks

Dehydrated, shaking, barely able to see straight, Hicks was in rough shape. I mean, really rough. His trainers, watching him fall apart, figured they needed to act - and FAST. Their “plan of action”, however, was so crazy that it’s hard to believe that it actually happened. They mixed a cocktail of strychnine - the same stuff people use to kill rats - and egg whites and gave it to Hicks. Unbelievable, I know, but back then, strychnine was thought to work as a stimulant in small doses. Hicks just swallowed the whole thing and kept going, though at this point, it was more like stumbling than running.

The effects of the strychnine kicked in pretty fast, and not in a nice way. Hick’s muscles began twitching uncontrollably, and his heart was racing out of control. What did his trainers do here? They doubled down on their terrible idea (yes), giving him another dose of strychnine - this time with a bit of brandy to, I guess, make it go down easier. Now completely delirious, Hicks had no clue where he was or what was happening. But with his trainers practically holding him up, he managed to keep moving forward. When he finally crossed the finish line, he collapsed on the ground and had to be rushed to medical attention.

Hicks won the marathon, but he was lucky to survive it. Later, he admitted he couldn’t remember much of the race, just the overwhelming need to make it to the end.

"Never in my life have I run such a tough course. The terrible hills simply tear a man to pieces."

Of the 32 men who started the race, only 14 actually crossed the finish line. Arthur Newton finished fifth, while Félix Carvajal still somehow managed to finish fourth despite his little food-poisoning adventure.

Len Tau, one of two South African Tswana tribesmen competing, finished ninth - despite having run the entire thing barefoot (honestly, that’s one of the more normal things that happened that day).

"Every difficulty encountered must be an opportunity for new progress."

This confusing mess of 1904 forced the Olympic organizers to rethink the marathon for future Games. By 1908 changes were already in place, and people began paying closer attention to the conditions of the course and the health of the athletes. Water stations became more frequent, and the days of “purposeful dehydration” thankfully were left behind as just another pathetic experiment.

The runners who somehow survived this event had their own peculiar stories to tell afterwards. Our guy Félix Carvajal, for example, kept running, even landing a sponsorship from the Greek government in 1906 to compete in the Intercalated Games in Athens. But Carvajal never made it to the starting line. He disappeared without a trace, prompting newspapers to mistakenly report his death. Then, as if it was all part of the plan, he reappeared a year later in Havana, alive and well, carrying on like nothing had ever happened.

In the end, I think this marathon might not have gone down in history for the right reasons, but it certainly taught the Olympic organizers one thing: if you’re going to put on a show, at least make sure the performers survive…

Amazing, Marina! Your article about the 1904 marathon is simply fascinating! The way you brought out the bizarre and chaotic details of this historical event truly captured my attention. I loved how you narrated this story, making it not only informative but also fun. It’s amazing how history is full of surprises, and you did a wonderful job of making us reflect on that. I can't wait for your next article! :-)

Welcome back Marina, as usual, you made feel like I was a fan watching the marathon race in 1904 live with your passionate writing skills