“I have frequently been questioned, especially by women, of how I could reconcile family life with a scientific career. Well, it has not been easy.”

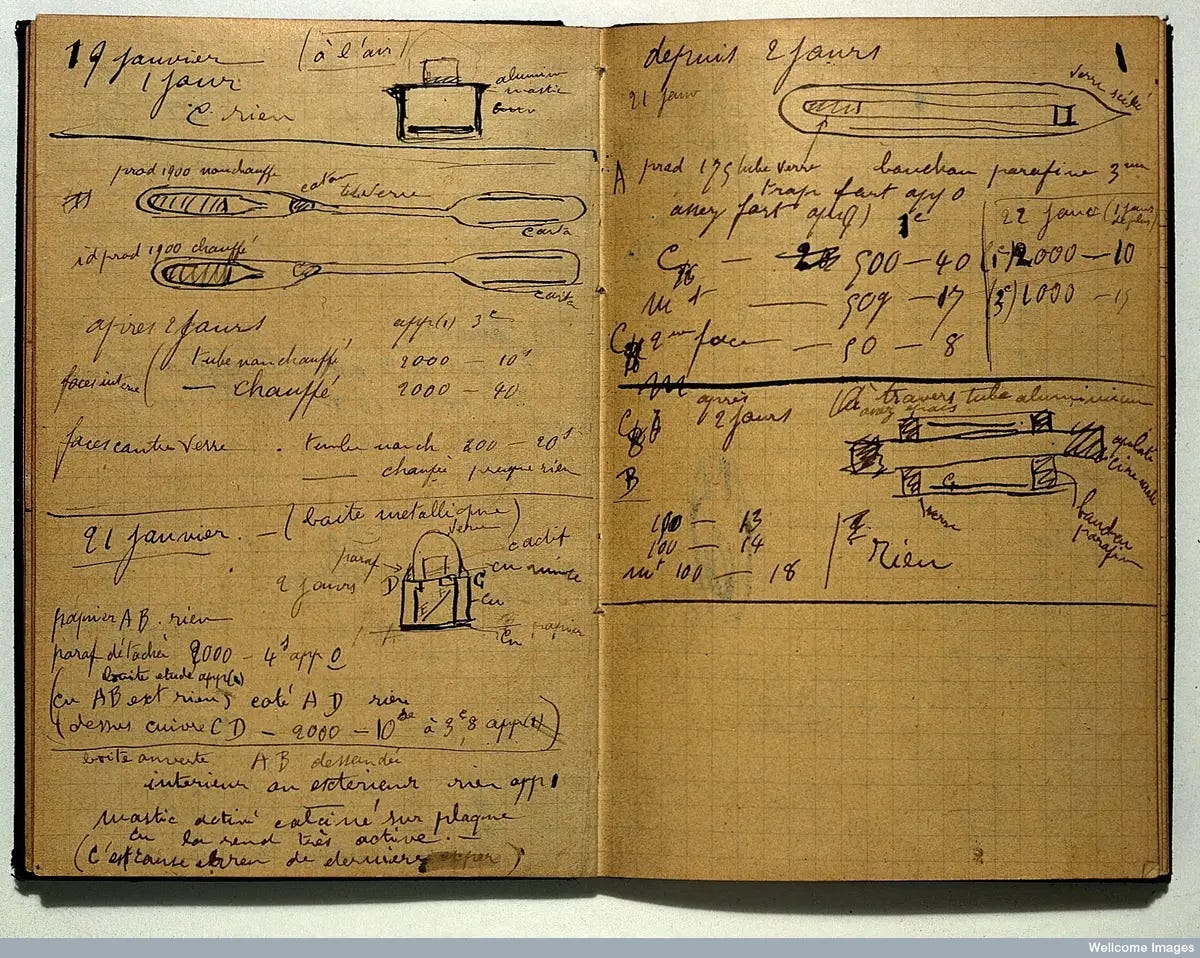

Marie Currie conducted her pioneering research often in difficult conditions and with inadequate laboratory equipment.

This phrase was articulated by one of the world’s most famous and celebrated scientists. Born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1867, Marie Curie would go on to become the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first and only woman to win the Nobel Prize twice (1903 and 1911), and the only person to win the Nobel Prize in two different scientific fields.

It surely must have been difficult for her to balance a brilliant and prolific scientific career with being a mother of two, but despite the challenges, she apparently did an excellent job: one of her daughters would eventually become a Nobel prize laureate as well - in 1935.

Print available

Marie Curie moved to Paris in 1891 to study physics and mathematics at the Sorbonne. There she met Pierre Curie, professor of the School of Physics, whom she married in 1895.

The couple began working together, often in difficult conditions and with inadequate laboratory equipment, on a pioneering research into invisible rays emitted by uranium – a new phenomenon that had been recently discovered by Professor Henri Becquerel, and which was latter called radioactivity. Their hard work paid off. The Curies announced the discovery of polonium, a chemical element, in July 1898, and the discovery of another element, radium, at the end of the year. Pierre passed away in 1906, knocked down and killed by a carriage.

During World War I, Curie saw an opportunity to use her knowledge to help save lives when she realized that the electromagnetic radiation emitted by X-rays could assist doctors in detecting and removing bullets and shrapnel embedded in the soldiers' bodies. She went on to develop a fleet of mobile X-ray machines for doctors on the front (she herself drove them to the front lines, aided by her daughter, Irene).

Despite her achievements and invaluable contribution to science and medicine (she founded the Curie Institute in Paris in 1920, and in 1932 the Curie Institute in Warsaw), Marie Curie faced resistance and opposition from male scientists in France, and never received significant financial rewards for her work.

She died on 4 July 1934 from aplastic anemia caused by exposure to radiation from her research: she carried test tubes containing radioactive isotopes in her pocket and stored them in her desk drawer, continuously exposing herself.

Still, after more than 100 years, much of Curie's personal effects including her clothes, furniture, cookbooks, and laboratory notes remain contaminated by radiation. Regarded as national and scientific treasures, her laboratory notebooks are stored in lead-lined boxes at France's national library in Paris.

“It is my earnest desire that some of you should carry on this scientific work and keep for your ambition the determination to make a permanent contribution to science.”