I was 25 when it all clicked into place, a classic case of better late than never - or so they say. You'd think living feeling extremely out of sync would raise some flags earlier, but here we are. Turns out, as I found out four years ago, I'm autistic. And today, of all days, is World Autism Awareness Day, a time when we're all supposed to be more aware, whatever that means.

Honestly, I've never been one to mark this day with any sense of celebration or purpose. For me, this is just another one of those occasions where everyone suddenly becomes an advocate for about 24 hours, social media gets swamped with emotional quotes on peaceful backdrops and dramatic declarations about the importance of understanding autism, and then the world forgets about the whole thing until next year. But I decided to skip the usual eye-roll this year, and take this opportunity to talk about autism with you, my dear unicorns, from our favorite perspective: a historical one.

Contrary to what some people might have you believe (yeah, looking at you, Karens), the story of autism actually dates back to around 1911. Yet, even with over a century of history behind us, it's both frustrating and almost comical how many people, particularly women, go through their entire lives without ever receiving a proper diagnosis. It seems that society (doctors included) still is as ready to identify and deal with autistic individuals as I am to run a marathon in high heels.

Take my amazing encounter at the dentist's office as an example. I had an appointment, and my partner had to tag along for moral support. The moment autism was mentioned to the receptionist, who had been chatting with me up until that point, I became invisible. She immediately stopped addressing me directly and instead channeled all questions through the person who was with me, apparently assuming that the word "autistic" is synonymous with "incapable" in social situations. Spoiler alert: it's not.

We've come a long way since the first descriptions of autism popped up in medical literature. Yet, as my delightful experience shows, we've still got miles to go.

“What is this place?” I asked of the man, who had his fingers sunk into the flesh of my arm. “Blackwell’s Island, an insane place, where you’ll never get out of”.” ― Nellie Bly, Ten Days in a Mad-House

For some people living in the early 1900s, the price of nonconformity was a one-way ticket to the nearest asylum. From the mentally ill to the merely eccentric, anyone who didn't meet the rigid standards of the day could find themselves locked away for the rest of their lives. Abuse and neglect were all too common in these institutions, and the treatments, if they could be called that, were often more harmful than helpful.

Over time, a small but growing number of people began to take notice and speak out against the inhumane treatment of asylum patients, arguing that mental illness was not a moral failing, but a medical condition that required compassion, understanding, and proper treatment. One such advocate was Nellie Bly, a pioneering journalist who, in 1887, posed as a mentally ill woman in order to gain admission to the Women's Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell's Island in New York City. Her resulting exposé, published in the New York World and later compiled into a book titled "Ten Days in a Mad-House," shocked readers with its vivid descriptions. Bly detailed the cruel treatment of patients, including being fed rotten food, being forced to sit for hours on hard benches without any form of activity or stimulation, and being subjected to ice-cold baths as a form of punishment.

Slowly but surely, the field of psychiatry, which had long been dominated by superstition and pseudoscience, began to embrace a more scientific approach to mental health. This shift in perspective was important for a deeper understanding of various mental health conditions, including those that had long been misunderstood or overlooked.

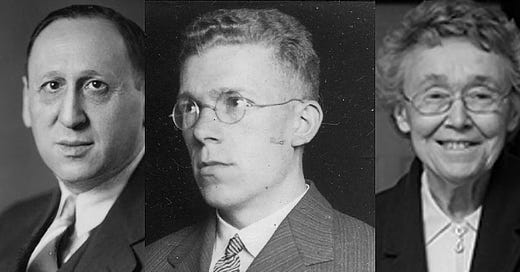

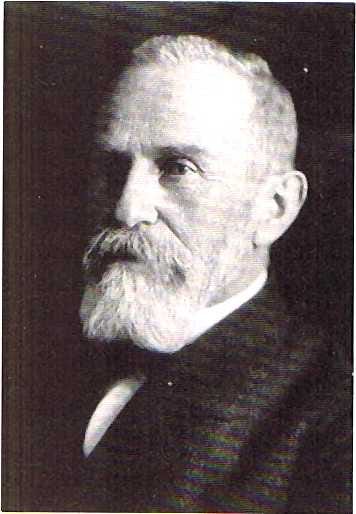

Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler was the first to introduce the term "autism", in 1911, but he used it to describe a particular set of behaviors he observed in patients with schizophrenia. Bleuler noted that these patients seemed to withdraw from the reality around them, retreating into their own inner world of thoughts and feelings.

“Not all the features of atypical human operating systems are bugs.” ― Steve Silberman, NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity

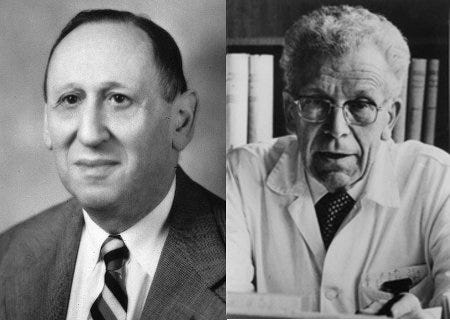

It wasn't until the 1940s though, in the midst of World War II (!!), that autism began to gain wider recognition as a distinct condition, thanks to the groundbreaking work of two doctors: Leo Kanner in the United States, and Hans Asperger in Austria.

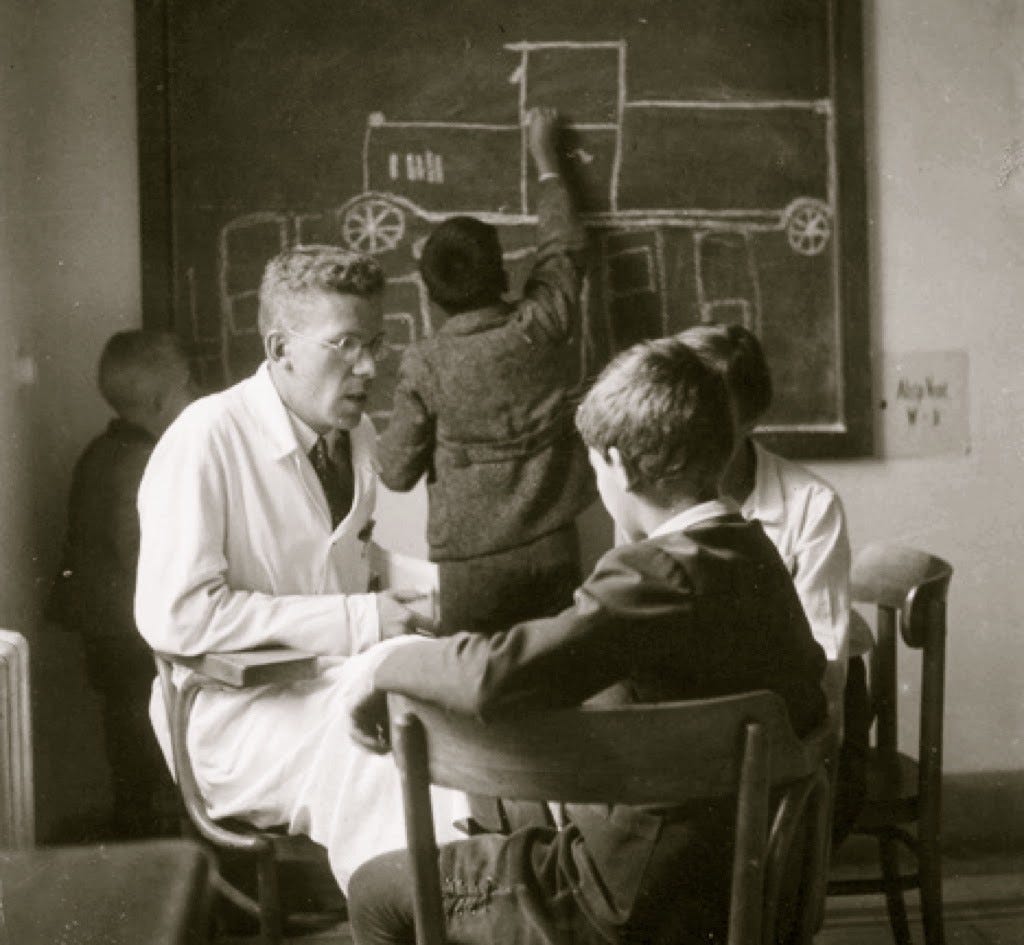

Kanner, a Ukrainian-born immigrant to the U.S., was the director of the Child Psychiatry Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. There, he encountered a group of 11 children who didn't fit the mold of any known condition at the time. In a revolutionary paper published in 1943, titled "Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact," Kanner observed, among other things, that these patients had a strong preference for solitude and an almost obsessive need for sameness and routine. They struggled with social interactions, often used language in unusual ways, if at all, and engaged in repetitive motor behaviors, such as rocking, spinning, or flapping their hands. Now, you might be wondering, what made Kanner's paper so important? Easy. Kanner was the first to propose that the traits he described represented a unique diagnosis. He repurposed the term "autism," emphasizing that this was an individual condition (not a symptom) that deserved to be studied and understood on its own terms.

The paper was not without its controversies and a fair share of bullshit, though. For example, in addition to describing the behaviors he observed, Kanner also suggested that the children's parents, particularly their mothers, were emotionally cold and detached, and that this might have contributed to the development of autism. I mean, of course. In any context, we can always blame the moms and call it a day.

“Not everything that steps out of line, and thus “abnormal”, must necessarily be “inferior”.” — Hans Asperger

While Kanner was doing his thing in the U.S., Hans Asperger was also studying children with similar traits over in Austria. In a paper published in 1944, he also wrote about children who had difficulty with social interaction and communication, but there was a key difference between his and Kanner's patients (who mostly had significant delays in language development and intellectual disabilities): Asperger noticed that some of the children he was studying had debilitating social challenges, but, at the same time, demonstrated having an average or even above-average intelligence and language skills. They could often speak quite well and had a big vocabulary, but still found it hard to have a proper back-and-forth conversation and to pick up on social cues and norms.

In simpler terms, Asperger showed that autism wasn't just one thing that looked the same in everyone. Instead, it was more like a spectrum, with a broad range of characteristics that could show up differently and with varying levels of intensity in each person. The logical conclusion was that there wasn't just one right way to support or treat these individuals but that approaches needed to be tailored to each unique situation.

As important and revolutionary as it was, Asperger's work was largely unknown outside of the German-speaking world until the 1980s, when it was rediscovered and translated into English. And that's when things got a bit messy. Because Asperger was working in Vienna during the Nazi era. And when his work came to the spotlight, some pretty heated debates about his involvement with the Nazi regime started to happen. Herwig Czech, a medical historian at the Medical University of Vienna, argues in a paper published in 2018 that Asperger didn't just collaborate with the Nazis but actively helped out with their eugenics program. According to Czech, the Austrian pediatrician referred children with disabilities to the infamous Spiegelgrund clinic, where many were killed as part of the Nazi's Aktion T4 program (and which I visited a few months ago. You can read about my experience here). This program was all about "cleansing" the German population of people deemed "unfit" or "unworthy of life," including those with physical and mental disabilities. Some historians, like Edith Sheffer, who wrote the book "Asperger's Children: The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna," strongly agree with Czech. But others argue that the evidence against the doctor isn't conclusive. They say that Asperger might have actually been a victim of the Nazi regime himself and worked to protect children with disabilities from the horrors of the time.

We might never find a definitive answer. But there's no denying that his work helped to reshape how we think about autism today.

“The world needs different kinds of minds to work together.” — Temple Grandin

I can't help but reflect on my own experiences. I know, I know – it's easy to assume that someone who's had a bit of success must be some kind of insufferable egomaniac. But I swear, that's not me. At least, not most of the time.

I have managed to carve out a pretty decent career for myself. And while I'd love to say it's all due to my sparkling personality, the reality is a bit more complex than that. Turns out, a lot of my success actually comes down to some of the abilities that I've got rattling around in my brain, the ones that just so happen to be linked to my autism. Just like the kids that Asperger observed, I fall into this weird place on the spectrum where enormous challenges coexist with what you may call "impressive skills and talents."

But let me be clear: I'm not here to claim that autism is some kind of magic key to success. Trust me, there have been plenty of times when I've wanted to give up and become a professional hermit. However, I can't ignore the fact that some of my autistic traits have been pretty damn useful.

If you're reading this newsletter, you likely already know that I spend most of my days restoring and colorizing historical photographs. It's a job that demands a serious eye for detail, which just so happens to be my specialty. I have this ability to zoom in on the tiniest details and notice things that most people would overlook. It's like having a built-in magnifying glass in my brain, and I'm not afraid to use it. In addition to that, I can spot the subtlest variations in hue and saturation, and I've got a memory for color that would put Pantone to shame. This can be explained by recent research, which suggests that visual processing (the way that the brain processes colors and visual details) can be enhanced in some autistic individuals. And when it comes to hyperfocus, well, when I'm working on something I'm truly passionate about, I can get so immersed that the rest of the world just disappears.

So, in a way, my autism helped me excel in my field and create work that I'm genuinely proud of. But even with all those skills and accomplishments, I still struggle with a lot of things that most people consider pretty basic. And that, more often than not, makes me feel pretty pathetic.

The simple thought of making a phone call can trigger a full-blown anxiety attack. Small talk, that thing that is supposed to be the social equivalent of a warm-up stretch, feels more like a linguistic obstacle course to me. And I won't even begin describing all the unwritten social rules and cues that everyone else seems to understand instinctively – except me. In fact, I like to say that if you've never found yourself Googling "is it socially acceptable to cross my legs three times during the same conversation" or something stupid like that, chances are you're not autistic.

“Autists are the ultimate square pegs, and the problem with pounding a square peg into a round hole is not that the hammering is hard work. It’s that you’re destroying the peg.” — Paul Collins

In the years following Asperger and Kanner's work, several other individuals made significant contributions to this field, notably Lorna Wing and Christopher Gillberg, in the 1970s and 1980s. The 1990s saw a surge in research with the development of standardized diagnostic criteria and assessment tools. Researchers like Simon Baron-Cohen delved into the cognitive and psychological mechanisms underlying the condition, such as the theory of mind and central coherence. In recent years, the neurodiversity movement has challenged traditional notions of autism as a disorder that needs to be "cured." Modern approaches to diagnosis and support emphasize the importance of personalized interventions and accommodations that build on an individual's strengths while addressing their specific challenges. However, despite these advancements, stereotypes and misconceptions persist, and access to quality services and support remains a challenge for many families.

I think there is hope for a better future. One day, we'll look back on all those old stereotypes and misconceptions and laugh. Well, maybe not laugh, exactly. More like cringe.

In the meantime, I'll be over here, embracing my autistic quirks and having anxiety attacks at the thought of someone saying "hi" to me at an unexpected time. And I think that's… okay?! Because let's face it – small talk is the real enemy here, not autism. And being "normal" is overrated anyway.

That's it for now. If you need me, I'll be hiding in my sensory-friendly blanket fort, thankyouverymuch.

I work in the mental health field, and have been saying for years that “normal” is a STATISTICAL term, with no place in psychology or medicine. Forget the bell curve, we are all unique data points.

Marina, we are so fortunate for you sharing your artistic talent with us. Your article exhibits your passion for life and the arts. You are correct how psychiatry has advanced over the years, I often ponder Dr. Egas Moniz receiving The Nobel Peace prize in 1949 for the lobotomy, shameful